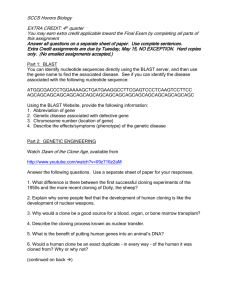

2 Models of Cloning

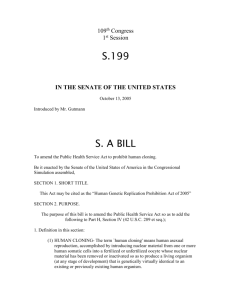

advertisement