Cloning - Kleykamp in Taiwan

advertisement

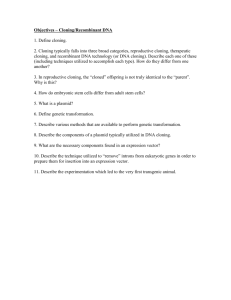

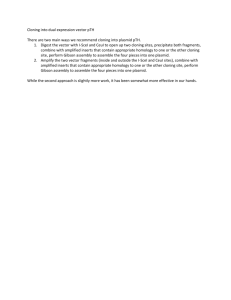

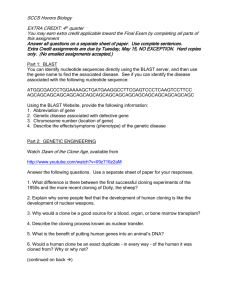

Disclaimer: This short article is being written by me to help students of English understand some of the basic science and ethical issues surrounding the method of cloning. I fully realize that I am not an expert on this subject, although I am perfectly qualified (as are all thinking adults) to make ethical judgments on subjects about which I have been informed. I have decided to present a bare outline of the scientific steps involved in cloning and proceed then to the ethical issues. The science is pretty much straightforward. It is illustrated on many reputable websites, such as Wikipedia. The steps involved in cloning are well understood, but the actual cloning of animals nevertheless appears to be very difficult to accomplish. Nevertheless the science of cloning is most certainly improving each day. The ethical issues involved are both numerous and controversial. I have based much of my information used in this short article regarding cloning and its ethical dimensions on the The President’s Council on Bioethics, Human Cloning and Human Dignity: An Ethical Inquiry (July 2002). Naturally, such a work could never be the last word on cloning, although I believe it is a sincere and inspired work. There will of course be some who disagree with its conclusions. Some Scientific and Ethical Issues of Cloning I. Introduction: I suspect that most students have heard of cloning, but very few students could actually explain precisely how cloning is done. Probably even fewer students have considered the ethical issues that arise with the cloning of a human embryo. However, the issues involved in cloning are indeed profound, touching our very notions of the definition and value of human life. Cloning presents us with moral dilemmas of whether life is sacred or whether life is something to be manipulated for a higher good. Unfortunately, there is no final authority on this subject. Instead, we must decide these issues based on our ethical beliefs and our consensus about what is moral and right. Religion can play a part in this, but only by helping us to infer what is true and appropriate. Nowhere in the Bible (or any other holy work) can one find a direct answer to the question of whether asexual reproduction is a sin. Nowhere can we find a direct answer to the question of whether a cloned embryo is a living soul or even a person. The ethical questions involving cloning often appear morally ambiguous; often upholding one moral principle while trespassing against another deeply held moral principle. It is incredibly difficult to hold a consistent moral position with regard to all aspects of cloning. Cloning can be seen as a force for good, saving lives, and reducing human suffering. And, it can also be seen as a force for evil, destroying life, and depreciating the value of a human being. Cloning can be seen as doing God’s will, or alternatively it can be seen as humans foolishly and arrogantly playing God. The stakes involved in these issues cannot be overestimated. They cut to the very core of what it means to be human. Perhaps this is why that the President’s Council on Bioethics was not ultimately successful at arriving at clear guidelines governing the ethical advisability of cloning for biomedical research. II. The Basic Science of Cloning The most common form of cloning involves two cells – one an egg cell taken from a female (let’s call her A) and the other an adult cell taken from whomever (let’s call this person B). Note that it is entirely possible that A and B are the same person – thus, B could be a man or woman. One could say that men potentially play a very small part in cloning. Men are biologically expendable. The nucleus (or the genetic material in the nucleus) of the egg from A is carefully extracted and discarded. The result is an enucleated egg, or an egg without a nucleus. The adult cell from B now has its nucleus (or genetic material) extracted and placed into the enucleated egg. The result is what is known as a zygote (or quasi-zygote) and after being treated with chemicals or after being shocked with a small amount of electricity, it begins to go through mitosis – splitting to form multiple cells. This splitting continues until an inner ball of cells and an outer ball of cells is formed (about 200-250 cells) and this is called an embryo. The inner ball of cells is composed of embryonic stem cells, which have become the focus of intense debate over whether it is morally right to kill the embryo and harvest these cells for biomedical research After 14 days the embryo begins the process of differentiation of its cells. Some of the stem cells will be converted to skin cells, other will become nerve cells, still others will become eye cells, etc. The process of differentiation follows the blueprint DNA largely contained in the nucleus of the cell. Some of the DNA is contained in the mitochondria, which is shown, in the figure above, as small black objects in the cytoplasm of the egg. The embryo can now be placed in a woman’s uterus (a surrogate) where it will attach to the wall of the uterus. The embryo will now begin to grow into a fetus and will be born in a normal fashion. The baby when born will be nearly 100% the same as the donor B when B was born. One major scientific problem concerns the use of adult cells in the cloning process. The trouble is that B’s adult cell is already differentiated – it is a skin cell, or perhaps a liver cell. When the nucleus of B’s cell is placed into the enucleated egg of A, and is shocked into mitosis, it will simply replicate a skin cell. But, cloning requires undifferentiated replication. Ian Wilmut and fellow researchers, who in 1997 cloned Dolly the lamb, solved this problem by using a cell that was going through a cycle of replication. If timed correctly, in line with the egg, the cloning will result in undifferentiated mitosis and stem cells will be created. The problem is solved. Another difficulty with this type of cloning (known as SCNT—somatic cell nuclear transplantation) is that there are many processes that are going on during differentiation of the cells. These processes are called epigenetic processes which involve complicated turning on and off of genes for specific purposes. To use adult cells in cloning, such epigentic processes in the adult cell must be reprogrammed to act as the DNA would prescribe in a normal zygote. If the reprogramming is not done correctly, then the embryo will not survive or will result in deformity at birth. This is one possible reason why there are so many failures in cloning. Reprogramming the epigenetic processes is a tricky business. It is possible, in some cases, to repair genetic disorders at the embryonic stage. The cloned (stem) cells are repaired of their genetic disorder and are guided in such as way that they differentiate into desired tissue, which can then be transplanted back into the donor. As they grow, new tissue is formed which does not suffer from the genetic disorder and the patient gets well. This is currently cutting edge biotechnology and has only been accomplished in animals such as mice. Nevertheless, it holds a promise for people suffering genetic diseases such as Parkinson’s disease. Note that the embryo must be destroyed in order to harvest the stem cells that can be used in the above manner. Despite the fact that cloning appears to be simple, it should be stressed that experts in the field of cloning readily admit that animal cloning is highly imprecise and typically results in a high percentage of failures. Wilmut states that in creating Dolly, 277 reconstructed embryos were tried, 29 of which were implanted into female lambs, only ONE of which developed into a live lamb. The fact that the science is still very tenuous makes it clear that, regardless of the other moral aspects, cloning of humans must not be allowed to go forward. The risks of birth defects and limited quality of life for cloned children are too high. The focus is therefore currently on the cloning of human embryos for purposes of harvesting their stem cells for biomedical research. We now turn to the ethical issues involved in cloning. III. Ethical Issues of Cloning Cloning of humans can be undertaken for two possible reasons: (1) To engage in cloning which results in the birth of a child (i.e., cloning for children) (2) To engage in cloning which yields human embryos and stem cells to aid in research (i.e., cloning for research) The first of these is generally thought to be morally indefensible. We should never clone humans for purposes of reproduction leading to the birth of a cloned baby. There are some who defend cloning for children, but these people form a distinct minority. Most countries currently have laws prohibiting cloning for purposes of having children. Here is a short list of reasons why that people might want to clone a child. Why clone a child? (arguments for) a. To provide a child to infertile couples. b. To allow single and same sex couples to have biological offspring c. To have children that have had genetic disorders repaired d. To have a source for genetically compatible organ replacements e. To replace a loved one who has died f. To be able to choose the genetic makeup of one’s children g. To replicate people having great talent or genius. It is easy to see that some of these arguments are simply silly, but others are not so easily dismissed. The broad feeling one gets is that such arguments indicate a favorable view of eugenics. Eugenics is generally frowned upon as a principle, but many countries have laws governing sex with the mentally ill. Eugenics is clearly behind such laws. Taiwan is no exception. Why clone a child? (arguments against) a. There is a problem of safety since there is a high risk of abnormalities. b. Consent to be cloned is special here since it involves a new and risky existence c. Women may gradually come to be exploited for their eggs d. Special problems of identity and individuality of those cloned e. Concern over the possible manufacture and commercialization of cloned humans f. Troubled family relations – a father could become his own son’s brother g. General effects on society – people might begin viewing children as mere tools Each of these arguments are strong, but it is clear that the health and safety risks borne by both the cloned child and the mother are exceptionally high and make an outright prohibition on the cloning of children the only choice. The ethical issues which surround cloning for research are much more ambiguous. We now turn to these. Why clone embryos and stem cells for research? (arguments for) a. We clone to better understand genetically based diseases. b. We clone to devise better treatment of diseases and paralysis. c. We clone to assist in gene therapy. While there appears to be fewer reasons in defense of cloning for research, the arguments are nevertheless very persuasive. Cloning of embryos for use in research is much less objectionable than the cloning of embryos which are then allowed to grow and develop to a live birth. The embryos which are destroyed to harvest stem cells are only 100 – 200 cells in size and have not differentiated into tissue, much less organs. It is hard to claim that this embryo is fully human, despite the fact that given the right conditions a human life is potentially there. It has been asserted that perhaps these embryos have a developing moral status that matches their increasingly complex physical development. Why clone embryos and stem cells for research? (arguments against) a. We all come from human embryos. b. Such research can gradually expand to involve mature or later staged embryos. c. It is immoral to create life just to destroy it, whatever the goal. Each of these is quite reasonable. There are strong arguments to place an outright ban on the cloning of human embryos for research. Nevertheless, the Council on Bioethics found itself divided in such a way that its final recommendation to the President of the US was to have a five year moratorium on human embryonic stem cell research. The purpose was to allow time for legislative bodies to hear arguments and better understand the public’s mood regarding cloning for research. Thus, the current state of recommendations in the US involves (1) a ban on cloning for children and (2) a five year moratorium on cloning for biomedical research. It would be interesting to know what the current regulations say here in Taiwan.