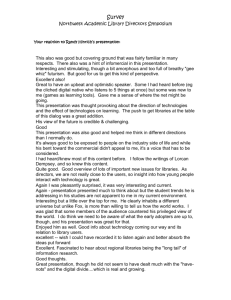

The digital library as place

advertisement