Contract Farming - International Association of Agricultural Economists

advertisement

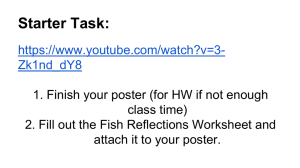

1 Contract Farming: Synthetic Themes for Linking Farmers to Demanding Markets Xiangping Jia Chinese Academy of Sciences Jos Bijman Wageningen University Abstract In the wake of emerging agro-food market and globalization, increased use of contract farming comes forth as apposition to markets for mediating exchange between farmers and midstream (and downstream) segments in developing countries. Contract farming is regarded as an integrated rural development strategy and a dynamic partnership by which small farmers can get access to market, technological and managerial assistance. Given the mixed evidence, a multi-dimensional viewpoint on contract farming at commodity level, territorial and sectoral level, and social-political level needs to be synthesized. As an institutional adaptation to changing technology and emerging global agro-food market, contract farming travels on multiple trajectories with local viability. Keywords: contract farming, vertical coordination, supply chain, agro-food market, rural institutions JEL: P51, L10, Q18 Xiangping Jia Center for Chinese Agricultural Policy, Chinese Academy of Sciences Institute of Geographical Sciences and Natural Resources Research Jia 11, Datun Road, Anwai, Beijing 100101, China Tel:(86)-10-64888985 Fax:(86)-10-64856533 email: xpjosephjia@gmail.com Jos Bijman Wageningen University Management Studies Group Hollandseweg 1 6706 KN Wageningen The Netherlands Tel. +31-317-483831 E-mail: jos.bijman@wur.nl 2 Contract Farming: Synthetic Themes for Linking Farmers to Demanding Markets 1 Introduction Producing and selling on a contractual basis is a common arrangement in agriculture all around the world. Contract farming (CF) has existed for a long time, particularly for perishable agricultural products delivered to the processing industry, such milk for the dairy industry or fruits and vegetables for making preserves. Towards the end of the 20th century, CF has become more important in the agricultural and food industries of the developed and developing countries. Spurred by changes in (international) competition, consumer demands, technology, and governmental policies, agricultural systems are increasingly organized into tightly aligned chains and networks, where the coordination among production, processing and distribution activities is closely managed (Zylbersztajn and Farina, 1999). Contracting between producers on the one hand and processing or marketing agribusinesses on the other hand is one of the methods to strengthen vertical coordination in the agrifood chain (Swinnen, 2007). The trend towards more contract farming, and the reasons behind it, have been extensively described for the agrifood industry in developed countries (Martinez and Reed, 1996, Royer and Rogers, 1998). Developing countries are impacted by the same trends in the agrifood system, and also experience an increase in CF. However, for developing countries there are a number of developments that may lead to an even more rapid expansion of CF. One of these developments is the rise of supermarkets in food retailing. Over the last two decades, the number of supermarkets has grown rapidly in the urban areas of developing countries, particularly in Asia and Latin America (Reardon and Berdegue, 2002). Supermarkets have procurement practices that favour centralized purchasing, specialized and dedicated wholesalers, preferred supplier systems, and private quality standards (Shepherd, 2005). These characteristics of the supermarket procurement systems require more vertical coordination among production, wholesale and retails, thus favouring the introduction of CF. Another development relevant for CF in developing countries is the reduction of the role of the state in agricultural production and marketing. As part of market liberalization policies, governments have often reduced their budgets for and direct involvement in providing inputs and technical assistance as well as in marketing farm products. As markets for the private provisions of inputs and services continue to fail, CF could solve the problems of farmer access to inputs (Key and Runsten, 1999). A third development refers to the ambition of donors, development NGOs and governments of developing countries to strengthen smallholder access to markets. These agencies consider CF as one of the main instruments to link small-scale farmers 3 to domestic and even foreign markets and thereby to reduce poverty (Dannson, et al., 2004, IFAD, 2003, World Bank, 2007). As CF arrangements often include the provision of inputs and technical assistance, participating smallholders can benefit from new market opportunities that would otherwise not be available to them as they would not produce the required quality. The intellectual popularity of contract farming reflects the evolved thinking of development strategies (Little, 1994). Contract farming was favored in the 1960s due to the ideological reflection and desire to “targeting rural poor”, the internationalized agriculture, and the dynamics of rural development strategies. The exclusion of smallholders from the Green Revolution in the 1970s makes many commentators and practitioners see contract farming as a viable tool to integrate small farmers into the industrial sectors. In the late 1980s, contract farming was initiated in Africa by various development agencies (such as the World Bank and USAID) with a perception to avoid government-related market and price control. The following intellectual favor to contract farming in the early 1990s was based on the emphasis of the private sector and market-led growth. However, market liberalization and the state’s quick withdrawal leave huge gaps between small farmers and markets. In the wake of internationalized agriculture and radical changes in agro-food market in developing countries, contract farming is regarded as one of the components for integrated rural development strategy and a “dynamic partnership” by which smaller farmers can get access to market, technological and managerial assistance (Little and Watts, 1994). In this context, contract farming is resurging on the development agenda as an innovative financial intermediation with the rise of integrated supply chains, as an adapted response to the stringent food safety standards, and as an effective tool for poverty reduction (WDR, 2008). The role of state as a catalyst in connecting smallholders to markets is re-emphasized in the meantime. This chapter does not aim to provide a comprehensive overview of the literature on contract farming, as a number of authors have provided thorough reviews (Eaton and Shepherd, 2001, Glover and Kusterer, 1990, Little and Watts, 1994). We do, however, make an attempt to broaden the intellectual debate and to argue for the study of multiple trajectories of contract farming. Additionally, our chapter aims to encourage scholarly discussions on a set of core practical concerns and concurrent theoretical questions that take us beyond the state of the art in the study of CF. The chapter is structured as follows. To form a synthesis, it starts with the thesis for a theoretical basis of contract farming. Then, following the procedure of dialectics, the antithesis is given in critical reflection on the dominant theory. A multi-dimensional perspective on contract farming is then elaborated to base the debate within a holistic and congruent framework, our synthesis. Finally, some key themes for research and policymaking are drawn up. 4 2 Thesis Contracts in agriculture have three distinct functions (Hueth, et al., 1999, Sykuta and Cook, 2001, Wolf, et al., 2001). First, they serve as a coordination device, allowing individual actors to make decisions (e.g. on resource allocation) that are aligned or need to be aligned with decisions of the partner(s). Coordination is meant to ensure that products of the right quantity and quality are produced, and delivered at the right time and place. For instance, contracts commonly specify the volume to be delivered to the contractor in order for the producer to know how much to sow or plant and for the contractor to know how much processing capacity to install. To a limited extent, coordination can be obtained by financial incentives. However, more detailed coordination requires information that cannot be transferred through prices but require contractual provisions on the obligations of each partner and on clarifying which partner may decide on those actions that are not stipulated in the contract. Second, contracts are used to provide incentives and penalties in order to motivate performance. Without proper incentives to each contract partner, no transaction will take place. Particularly when the contractor demands specific activities from the farmer, for instance in the case of special quality, the contract clarifies what compensation the farmer will obtain for these activities. The contract can include an agreement on the price, but it can also indicate what price determination mechanism will be used to decide on the proper compensation. Third, the contract clarifies the allocation of risk. For example, farmers can mitigate the risk of income loss due to poor yield by signing an agreement with a contractor that specifies a portion of compensation independent of realized yields. Contract farming is often presented as an institutional arrangement used for organising vertical coordination between growers and buyers-processors (SOURCES). Vertical coordination means that the activities of sellers and buyers are closely aligned. As supply chains (or value chains) are characterized by sequential transactions, vertical coordination implies that the transactions upstream (such as between producer and processor) are aligned with transactions downstream (such as between processor and distributor). These upstream and downstream transactions become increasingly interdependent, for example when a processor has invested in establishing a consumer brand for his products. In order to protect this brand from devaluation by not fulfilling customer expectations, processors try to control any process that can negatively affect the value of their brand.1 Not all transactions with agricultural products are suitable to be governed by a CF arrangement. As CF involves costs for both producers and contractor, these costs must 1 Vertical coordination in agrifood chains in developed countries has been widely studied in the 1990s (Frank and Henderson, 1992, Galizzi and Venturini, 1999, Royer and Rogers, 1998), while studying vertical coordination in developing countries is a more recent phenomenon (Swinnen and Maertens, 2007). 5 be outweighted by the benefits, and the balance of cost and benefit of CF must be larger than with other arrangements for selling/buying the product. The cost of carrying out a transaction between buyer and seller (in our case a farmer and its customer) are commonly called transaction costs. Transaction costs generally increase when more vertical coordination between seller and buyer is needed. Thus, studying the vertical coordination requirements provides indications on why particular arrangements will be used. The type and intensity of vertical coordination depends on the type of products and the demands from processors, retailers and consumers. Minot (2007) has made a useful distinction in the factors that influence the need for vertical coordination: (1) the type of product; (2) the type of buyer; and (3) the type of destination market. Contract farming is a broad concept which encompasses many different types of arrangements and contract provisions, and many different services included or not in the agreement. All of the literature on contract farming emphasizes the diversity of contractual arrangements between farmers and contractors. This diversity is a result of the technical requirements of production and the associated production and transaction costs (Simmons, et al., 2005). To structure the multiple contracting arrangement, a typology of agricultural contracts may be helpful. A classical typology of contracts between farmers and their customers has been made by Mighell and Jones (1963), who distinguish between market-specification contracts, production-management contracts, and resource-providing contracts. These contracts differ in their main objectives, in the transfer of decision-rights (from the farmer to the contractor), and in the transfer of risks. A market-specification (or marketing) contract is a pre-harvest agreement between producers and contractors on the conditions governing the sale of the crop/animal. Besides time and location of sales, these conditions include the quality of the product, thus affecting a few of the production decisions of the farmer. The contractor reduces the producer’s uncertainty of locating a market for the harvest, but the farmers continues to bear most of the risk of his production activities. The production-management contract gives more control to the contractor than the market-specification contract, as the contractor will inspect production processes and specify input usage. Producers agree to follow precise production methods and input regimes, which implies that the farmer has delegated a substantial part of his decision rights over cultivation and harvesting practices to the contractor; he is willing to do so because the contractor takes on most of the market risks. Under the resource-providing contract the contractor not only provides a market outlet for the product, but he also provides key inputs. Providing inputs is a way of providing in-kind credit, the cost of which is recovered upon product delivery. How much decision-rights and risk is transferred from the farmer to the contractor depends on the actual contract. While this typology has been used by many authors, it has recently been criticized by Hueth et al. (2007) for being of little value for understanding contemporary agricultural contracts. Their main point of critique is that this distinction does not hold 6 in practice as most contracts combine elements of marketing (which is the interest of the farmer) and coordinating production (which is the interest of the contractor). Minot (1986) has discussed how the three different types of contracts can solve particular transactional problems (when comparing contract farming with spot market transactions). A market-specification contract can reduce the cost of gathering and exchanging information about demand, quality, timing and price, thus reducing uncertainty and the concomitant market risks. By increasing information exchange, a market-specification contract reduces coordination costs (as compared to spot market trading). Coordination costs are particularly present in the case of (1) perishable products supplied for processing, exports or supermarkets; (2) complex quality products; and (3) new (niche) markets. The resource-providing contract can reduce the costs of obtaining credit, inputs and extension services, including the cost of screening and selecting these services. This type of contract is typically applied in the case of crops for which the quality of the output depends on the type and quality of inputs, as well as in the case where inputs provision reduces production costs for the farmer and thereby purchasing costs for the contractor. Finally, the production-management contract specifies cultivation practices to achieve quality, timing and least-cost production, thus even more economizing on coordination costs. It may also support skills development of the producer, and thereby reduce future transaction costs. 2.1 NIE Perspective on Contract Farming Theoretically, contract farming is often explained using the lens of New Institutional Economics (NIE), more specifically Transaction Cost Economics (TCE). Central in NIE and TCE is the idea that all transactions between economic actors involve transaction costs. These costs relate to finding a market/customer, negotiating, signing a contract, controlling contract compliance, switching costs in case of premature termination of the contract, and all lost opportunities. Transaction costs appear in different forms, but are mostly caused by uncertainty and/or asymmetric information. In the presence of high transaction costs, non-standard contracts may be effective at reducing the overall costs in the presence of high risks and asset specificity. In smallholder agrarian economy, NIE analysis is “open to the possibility that, under circumstances where standard competitive spot markets for inputs and credit fail due to high transaction costs, interlinked or interlocked transactions may be transaction cost efficient . . . [to] allow imperfect markets to develop where the alternative is complete market failure” (Dorward, et al., 1998). Transaction costs are overwhelmingly present in rural economies, particularly of developing countries, not only because of missing inputs markets and substantial asymmetries of information in output markets, but also because of the small scale of most farming production units compared to the size of their trading and processing customers. Even in the case of increased mechanisation, the dominant farm ownership structure continues to be the family farm, where farm land is owned by the nucleus 7 family, most of the labour is provided by family members and all of the management is the responsibility of the head of the family. This model has been explained as an efficient response to on-farm incentive problems (Binswanger and Rosenzweig, (1986). In the presence of incentive problems under the assumptions that individuals dislike effort, the information asymmetry makes supervision and monitoring costly. As a result, hired labour force is perceived less efficient than family labour. Family ownership of farmlands by smallholders is found to be efficient and egalitarian (Binswanger, et al., 1995). But the scattered family ownership exacerbates the transaction cost in rural economy, and imposes challenges in the agro-food market where downstream intermediaries face constraints in the delivery of proper quantities and qualities. In the context of overwhelming transaction costs and information asymmetries, the simple market exchange is found to be inefficient. Contract farming is thus an institutional response to the high transaction costs related to transactional risks and coordination costs. Contract farming should not be considered as a form of vertical integration, but it should rather be specified as “vertical coordination”. Vertical integration implies bringing the transaction within the boundaries of the firm, thus eliminating contractual exchanges or market exchanges (Perry, 1989). But under a contract farming arrangement, the ownership of the farm does not change. The downstream processors or retailers do not take ownership of farm assets, but do specify in more or less detail the use of those farm assets. But similar to vertical integration, contract farming arises (partially) from transaction economies – which are associated with the process of exchange itself – and market failure that consists of imperfect competition and asymmetric information. From viewpoint of transaction cost economics, for example, farmers’ careful use of chemicals and nutrient-enhancing seed varieties is “asset specificity” that is costly to exchange in spot market. In the form of vertical coordination, contract farming substitutes contractual exchanges for a market exchange. Such contractual arrangements “bridge the gap between vertical integration and anonymous spot markets” (Perry, 1989). In order to economize on production and transaction costs, transaction parties (bilaterally or unilaterally) choose the most efficient institutional and organizational structure (Williamson, 1985). These governance structures can be classified on a continuum ranging from spot market to hierarchy (or vertical integration). In between these extremes, many so-called hybrid arrangements can be found, combining price (as the dominant governance mechanism in markets) with authority (as the dominant governance mechanism in a hierarchy). Contracts are a typical hybrid governance structure. Hybrid governance structures are typically characterized by three elements: pooling, contracting and competition (Ménard, 2004). The pooling resources refers to aligning the deployment of individually owned assets as well as joint investments. 8 Pooling results in interdependencies which requirs bilateral coordination for efficient resource use. Competition refers to the continuation of some form of competition between individual partners in the hybrid governance structure. This competition can be both among different farmers participating in the contract farming scheme and between farmers on the one hand and their customer on the other hand (so-called vertical competition). Different from vertical integration, where the function of markets is replaced by the function of managerial discretion, a hybrid arrangement continues to make use of the motivational and coordinational impact of prices. While hybrid arrangements are distinctly different from market and hierarchy, there still is a broad range of different organisation structure that fall within this category, such as short or long term contracts, bilateral or multilateral contracts, consortia and strategic alliances, and all sorts of joint ventures. It is the combination of (risk of) opportunism and (risk of) miscoordination that eventually determines the particular governance characteristics of the hybrid. For example, in their investigating in China’s emerging farmer cooperatives, Jia et al. (2010) find that farmers in China’s cooperatives mostly pool their decision-making in marketing inputs and outputs but still retain the majority of decision rights of production at the backyard. As a mixture of market governance and vertical coordination, individualism is the optimal organizational structure in China’s farmer cooperatives. 3 Antithesis Although contract farming can reduce transaction costs, it cannot completely solve the problems of opportunism and underinvestment in specific assets. As long as there is information asymmetry, one party may exploit an exchange at the expense of the other party. At regional and national level, contractors frequently seek market monopolies or concessions from the government to protect their investments. At individual level, small farmers, who face increased dependency and indebtedness with contracts, might be exploited by monopsonistic traders. On the other hand, farmers might divert the supported inputs to non-contracted use or sell their contracted produce to others. This type of market leakage is a common problem and has led to the failure of many contracting schemes (Eaton and Shepherd, 2001). The downstream traders, processors, or retailers will not invest in physical and/or human assets if they face the risk of opportunism by the farmers. To sum up, the “vertical coordination” of contract farming does not remove the possibility of opportunism and hold-up, and leads to weakened ex-ante investment incentives. Contract farming attracts to NGOs and donors because, as a “private-sector” commercial venture, it is considered to be financially sustainable. Moreover, contract farming assumes a market orientation as the initiative of the contracting schemes resides with the downstream customer. But the record of contract farming reveals that market instability and management problems frequently make contracting schemes unsustainable in the long run (Little, 1994). 9 The “antithesis” associated with contract farming reflects that the contractual arrangement does not only constitute of a business model involving different economic actors seeking an efficient and effective exchange model. CF should be placed in the wider scope of rural development, where public agencies as well as NGOs may play a major role in promoting and structuring CF schemes. To better understand and improve the use of contract farming as a development strategy, a comparative approach that recognizes the alternative market contracting structures and dynamics of governance helps understand the synergistic relationship between theories and empirical findings (Joskow, 2005, Ménard and Klein, 2004). In this respect, the NIE approach to industrial organization fails to explain the multiple trajectories of capitalist development of agro-food market (Hart, 1997). A multi-dimensional framework that includes formal and informal elements of the institutional environment as well as existing social capital and social norms is needed (see Figure) [INSERT FIGURE HERE] 4 The Multi-dimensional Scope of Contract Farming Analysis 4.1 Commodity Dimension Contract farming varies with the attributes of agricultural commodities. The biophysical characteristics of a commodity affect the transaction costs in agro-food markets. Also the degree to which the crop production cycle involves technical sophistication and equipment specialization (i.e. asset specificity), to which inputs require specific capital and labor complementarities (i.e. complexity), and to which quality is difficult to measure (i.e. uncertainty) affect transaction costs (Figure, left side). For example, simple marketing contracts are often used for fruits and vegetables between farmers and traders because of the perishability and price volatility. In comparison, for poultry meat and vegetables-for-processing, farmers enter into production contracts where specific standards are required by downstream processors and retailers because farming activities have to be coordinated with processing and marketing activities to prevent losses due to a lack of synchronisation. Some crops (e.g. cotton) that demand specific inputs (e.g., specific agrochemical combined with proprietary (BT) seeds) also favour production contracts. Jaffee and Morton (1995), in their exploration on the high-value crops in Sub-Saharan Africa, conclude that the organization and the performance of private marketing and processing are commodity-specific. The distinctive techno-economic characteristics of individual commodities influence the level of uncertainty and asset specificity. Vertically integrated or contract-based systems have institutional advantages for commodities that demand more investments in physical or human 10 assets and whose difficult-to-measure quality needs to be safeguarded through sequential stages of the supply chain. In general, food safety and quality standards favour more vertical coordination and therefore more contract farming. Food safety and agricultural health standards have become an increasingly important influence on the international competitiveness of developing countries, especially for high-value agricultural and food products (Jaffee and Henson, 2005). While public standards and market policies represented by international organizations are crucial in regulating the market, there has been a rapid rise in private standards that have reshaped markets in developing countries. Furthermore, as the main link between consumers and the food chain, retailers are responsible for translating consumers’ demands back up the chain and for organizing the flow of products back down to consumers (Fulponi, 2007). The replacement of global private standards imposed by multinational retailers for domestic private (or even public) standards reshapes the market structure and affects agricultural contracts. But the commodity-based approach has a limitation in that the politico-economic and social contexts of contract production are not properly specified. An overemphasis on commodity characteristics cannot capture the significance of political, historical, and social contexts of contract farming. Success and failure have often more to do with the (non)sustainability of particular ventures than with technological and commodity-specific characteristics (Little and Watts, 1994). Furthermore, individual commodity-specific observations lead to fragmented evidence. Cross-commodity studies comparing contract provisions are needed (Hueth, et al., 1999). 4.2 Territorial and Sectoral Dimension Writings on contract farming using a NIE perspective have mainly concentrated on the efficiency effects of different governance structures. However, the analysis at transaction level is incomplete in neglecting the pre-existing market power that heavily affects contractual arrangements (Figure 1, right side). Existing market structures matter for farmers’ bargaining position, and affect the sustainability of contractual arrangements. Rather than being separate, the exploration of territorial and sectoral dimensions complements the commodity-specific analysis at commodity and household level. The concept of supply chain is relevant here, as most transactions between farmers and their first customers (traders or processors) can only be understand when the transactions between traders/processors and retailers are included in the analysis. As the retailers are nowadays the dominant actors in the food market, particularly where it concerns value-added products like meat and vegetables, the bargaining power of these supply chain actors need to be taken into account. The literature on global value chains can inform the impact of power asymmetry in supply (or value) chains on the governance of the different transactions and thus on the type and content of contracts being used (Gereffi, et al., 2005). 11 In addition, local social and cultural heritage affects the type and scope of contract farming arrangements. While the changing bases and forms of globalization impose exogenous effects, territorial endogeneity at local level that is mediated by inherited structures, institutional complexities and spatial differences, confounds the analysis due to the difficulties of partitioning mixed effects of globalization and localism. This 2 ambiguity further hinders the puzzle of multiplicity of farming styles. Future research on contract farming therefore needs to go beyond traditional value chain, and to combine commodity-specific and sectoral dynamics, and, consequently, to reveal the diversity of agro-food market and territorial settings. 4.3 Social-political Dimension Market power at sectoral and supply chain level, and socio-cultural elements at territorial level, however, are only one dimension determining contractual forms (Figure). Behavioural norms that are rooted in rural communities, with its embedded social capital, are also decisive. Agricultural contracts feature distinctive simplicity, and their enforcement pervasively relies on informal mechanism – for example, conventions, reputations, and repeated interaction (Allen and Lueck, 2002). Neither the traditional production-market perspective nor the NIE approach to organization is able to cover the full concept of contract farming. While the NIE approach fails to explain the origins of agrarian settings, the production-market perspective cannot explain how adaptive institutional arrangements may support (or undermine) rural development. Nor do they answer how social norms can be mobilized to facilitate the sustainability of contract arrangements (Lazzarini, et al., 2004). To better understand the multiple trajectories of contracting in agro-food market, studies on local networks 3 and institutions are crucial (Hart, 1997). Such studies, however, are scarce. 2 Menard and Klein (2004) remark the variation in agrifood organizations in United States and European Union from a viewpoint of history, path dependency and local conditions. For example, European farms tend be smaller than US farms and more tightly interwoven with urban agglomerations. So European agriculture is more closely tied with local economic, demographic, and cultural differentiation. 3 The propositions of new institutional economics in the agrarian literature is criticized for their crude separation of purely economic relations and those involving extra-economic coercion or ‘non-economic’ forces (Hart, 1997). Quite often, the enforcement of agrarian contract invokes a particularly crude form of extra-economic coercion, for example the interlocked input and credit. In her illuminating article, Hart (1997) suggests: “[T]he processual approach taking shape in the agrarian literature grounds the exercise of power in specific institutional and political-economic contexts. A key insight is that struggles over material resources, labour discipline, and surplus appropriation are simultaneously struggles over culturally constructed meanings, definitions, and identities. Social institutions are conceived of not as bounded entities of social structures, but as multiple, intersecting arenas of ongoing debate and negotiation, the boundaries of which are fluid and contested . . . . [The] processual understanding of multiple trajectories at different societal levels provides a means of 12 5 A Development Agenda A myriad of studies on contract farming have sought to explain its existence, economic efficiency and distributional effects (Glover, 1994, Glover and Kusterer, 1990, Henson, et al., 2008, Key and Runsten, 1999, Little and Watts, 1994). The intellectual popularity of contract farming is increasingly responded by the operational development strategies (WDR, 2008). To complement with the richness of the literature and to draw a multi-dimensional perspective into the analysis of this institutional arrangement, the following attempts to highlight important themes that invite further elaboration. 5.1 Employment Effects, Labor Decision and Transformation Contract farming is by nature an institutional variant in agrarian economy that peasants are relegated to being hired on their own land. Discovering the disguised wage relationship between contractors and growers is crucial to observe the dynamics of rural transformation in the context of globalization and the emerging agribusiness. Farmers might contract with domestic retailers (or processors) directly as independent suppliers. They might also work as tenants for parastatal entities. Alternatively, they may transform to wage-earning classes as casual workers (on a task-by-task basis) or permanent workers (on multiple tasks). As a result, globalization and liberalization sweep agrifood market in developing countries and affect the dynamics of agrarian society. The employment effects of contract farming have on-farm and off-farm elements. The on-farm employment is regarded as a major benefit of contract farming investments because of the labor-intensity of crops themselves (Little, 1994). To the extent that farmers are vertically coordinated with downstream traders, the pathway by which agriculture is transformed varies. The more a smallholder is integrated – in other words, the less she diversifies her sources of income – the more likely farming will evolve into a wage-based activity without changing the land property rights. But strong coordination may imply increasing dependency and indebtedness. The on-farm employment effects are therefore influenced by the extent to which transaction costs are reduced. Policy interventions that mitigate risk and support ex-ante investments promote the on-farm employment associated with contract farming. Contract farming also creates indirect off-farm opportunities. When transaction costs are (partially) mitigated with contractual arrangements, processors, traders or retailers get incentives to invest in physical and human asset specificity (e.g. packing, storage, transportation, extension service and other supporting services), which generate spillovers to labour demand in the rural economy. Since most of the processing facilities for products like fruits, vegetables, sugar and tea are located near navigating between the determinism of ‘only one thing is possible’ and the voluntarism of ‘everything is possible’. . . ” 13 production zones, contract farming has high non-farm employment effects. Nevertheless, Little (1994), after reviewing a line of studies on contract farming in Africa, concludes that the non-farm employment effects are tied closely to the type of commodity produced and whether or not it requires processing or other value-added activities. For example, the contracted sugar and low-perishable vegetable schemes in Kenya has a worker-to-contract grower ratio of 1:6; for 6 contracted growers, 1 non-farm employment is generated. But for fresh-produce schemes, the spillover effect is not significant. Little (1994) therefore argues that, unlike the agro-industrial schemes, the fresh-producing contracting schemes employ few off-farm workers. Little’s conclusion, however, is rather static. With the improved information and logistic technology, such commodity-specific constraints are changing. The emerging agro-food market imposes both opportunities and challenges to smallholders. In deploying and developing the supply chain, the modern retailers not only shape the production and market, but also affect labour division. The coordination of farmers with downstream retailers and processors shapes the civil society at social dimension in rural economy, especially the distributional effects that we shall present in the next section. 5.2 Equity and Social Dimension The rural farm and non-farm activities targeted in poverty reduction may have variable impacts in terms of distributional effects (Ravallion and Datt, 2002, Start, 2001). As contract farming has long been voiced as a poor-targeted tool, its distributional effects should be examined from a broad perspective. Nevertheless, farmers are facing a mix of opportunities and challenges in the transforming agro-food markets. A line of evidence in Central and Eastern Europe, South America and Africa shows that the exclusion of small farmers is widespread where incentives and capacities are insufficient (Dolan and Humphrey, 2000, Humphrey, et al., 2004, Maertens and Swinnen J, 2009, Weatherspoon and Reardon, 2003). By contrast, a growing body of evidence shows income improvements of small farmers in developing countries when they are complying with standards along the agro-food supply chain. Such pro-poor institutions feature the various usage of vertical contractual arrangements. For example, Dries and Swinnen (2004) find that the rise of contracting improves small farmers’ access to credit, technology, and inputs; the compliance with high standards in vertically coordinated supply chains implies increasing benefits for small farmers. In addition, market structure determines the performance and distribution of various market segments of the supply chains. In an extreme case of a single monopsonistic multinational company, Maertens et al. (2008) found complete exclusion of small farmers, which the authors called a “worst case scenario”. In a case of distinctive agro-food market in China, a great number of upstream farmers, midstream trading firms and processors/retailers are in fierce vertical competition (Huang, et al., 2007). By observing the fruit and milk sector in China, Huang et al. 14 (Huang, et al., 2010, Huang, et al., 2008) find no exclusion of small farmers and 4 increasing coordination in modern marketing chains all the way to the farm level. In his review article on contract farming in Africa from development perspective, Little (1994) notes that the benefits of contract farming have accrued to larger and more profitable plantations whose proprietors tend to be urban or semi-urban-based farmers rather than local peasants; poorest farmers in the region are rarely recruited as contract growers. Furthermore, employment demand transforms towards more skilled, educated and knowledge-equipped farmers. Returns of labor in contract farming are low, and contract farming becomes a mode of income diversification for poor farmers. If the capitalist industrialization proceeded with the global supply chain affects the social formation by dominating industry and the urban bourgeoisie, the distributional effects would be a haunting agrarian question in any substantive sense. Small farmers may have substantive cost advantages, particularly in labor-intensive, high maintenance, and production activities with relatively small economies of scale (Birthal, et al., 2005). Furthermore, processors may prefer a mix of suppliers in order not to become too dependent on a few large suppliers (Swinnen, 2007). Contract farming may “have future perspective when effectively organized”. The inequality issue about contract farming is certainly not a black or white debate. The inequality effects may not be the original or sole cause as the interwoven effects between contractual forms and commodity-territorial-social complexities results in difficulties in explaining the existing mixed picture. The diversity of contract farming arrangements and varied success show a mixed picture and a dilemma to balance monopsonistic buyer and smallholders’ benefit. The agribusiness firms indeed recourse to monopsonistic power to contain side selling by farmers. But countervailing mechanisms are also needed to protect the interests of contracting farmers. The nuance calls for a continuing search for alterative institutional innovations of aligning farmers’ and companies’ incentive and of reducing transaction costs and uncertainty (Poulton, et al., 2005). 5.3 Multiple Trajectories and Dynamics of Contract Farming The globalization imposes mixed opportunities and challenges to developing countries, where domestic and regional markets may evolve to different pathways in response to the changing situation. A “bimodal” market segment of modern and traditional supply chains was predicted by Jaffee and Henson (2005: 99). Nevertheless, despite the centrally coordinated global interfirm division of labour involving global outsourcing blessed by FDI, there exists a much more nuanced and heterogenous map within the agro-food system (Goodman and Watts, 1997). The process of restructuring in regional and national agro-food markets is situated at multiple scales. Future 4 While little evidence was found that smaller farmers were discriminated by contracting firms in China (Miyata, et al., 2007), there is a tendency toward selecting a small number of medium-to-large firms (Hu, et al., 2004). 15 research calls for an interdisciplinary perspective which combines NIE and social capital literature to illustrate on the embeddedness of local complexities and on the emphasis of uneven and spatially differentiated impacts of globalization. The multiple trajectory allows for a viable role of the state. Government efforts can become cost-effective by coordinating activities along the supply chain (WorldBank, 2006). The involvement of local government streamlines responsibilities and reduces the enforcement problem of complying with food safety standards. The shortcomings of this mode have also been noted. The lack of interagency cooperation among the contracting company, village cadres, and farmers may eventually lead to a collapse of the venture (Eaton and Shepherd, 2001). A topic less touched upon in current literature is the interaction between agricultural production-market organizations and technology. For example, advances in measurement technology allow for automatic sorting and grading into different quality classes. Such a technological progress makes the use of quality-based payment relatively attractive (Hueth, et al., 1999). For agricultural products that rely mainly on physical properties for quality measurement (e.g., shape, size or volume), technological progress undermines contract farming because processors can fulfill the transaction at spot and open markets. Furthermore, the traditional role of the state in providing “public goods” to address market failures (e.g., the under-provision of inputs by the private sector) is likely to be reassumed by markets because of the technology progress. Since market failure partly arises from the property of non-excludability or non-rival externalities of private investments and from informational problems, technological progress – particularly the information and communication technology (ICT) – may allow for providing the previously non-excludable services and goods at reasonable costs (Dorward, et al., 2006). ICT, when applied in contract farming arrangements, affects agrarian society and social class. While localized social capital and social norms reduce transaction costs, the emerging information technology reduces the importance of collective action efficiency benefits, and thus may undermines the sustainability of farmer cooperatives. Contract farming needs thus to be examined from a dynamic perspective, with the changing viewpoint of the state’s role, technology progress, and social-political complexities. 6 Conclusion In the context of technological progress and market liberalization, the domain and boundary of the study of the organization of agricultural production, distribution, and marketing have been changing. The increasing need for vertical coordination leads to an increase in the use of contracts as opposed to markets for mediating exchange between producers and their processing/retail customers. Emphatic rhetoric to the contrary, contract farming represents the antithesis of free market forces. 16 As an hybrid arrangement between vertical integration and open spot market, contract farming faces the same contractual dilemma’s as other incomplete contracts, viz. prohibitive costs of specifying the full range of contingencies and restraining opportunistic behavior. As Williamson (1971) insightfully notes, the advantages of such vertical coordination “are not that technological (flow process) economies are unavailable to non-integrated firms, but that integration harmonizes interests . . . and permits an efficient (adaptive, sequential) decision process to be utilized . . . . ”. This paper synthesized a variety of expositions on contract farming. Rather than serving as a review on existing thoughts, we base the origin and evolution of contract farming on New Institutional Economics. A multi-dimensional viewpoint on contract farming at commodity level, territorial and sectoral level, and social-political level are elaborated to integrate this institutional adaptation into a broader context. The resurgence of contracting farming is far more than an instantaneous response to the emerging global agro-food regime. Rather, contracting farming is reconfigured in new institutional relations and new divisions of labors such that contracting out production activities is a driving force at social dimension. To analyze contract farming, a comparative governance approach that recognizes the alternatives and dynamics of governance structures helps to understand the synergistic relationship between theories and empirical findings (Joskow, 2005). To better understand the idiosyncracy and dynamics of contract farming, a multi-dimensional perspective (at commodity-specific, territorial and sectoral, and social-political level) needs to be elaborated in more empirical research. The enthusiasm and inflated expectations about the development potential of contract farming should be constrained. Contracting schemes work well when they are adapted to local contextual complexities. Having a great number of variants, contract farming is far more than a tentative response to the imbalance between the concentrated (downstream) supply chain and the dispersed (upstream) growers, but an embedded institutional arrangement with local viability. After all, the diversity and variations of contract farming are rooted in specific political and economic structures, and are linked to specific agricultural commodities and production processes. Food travels over long physical and social distances and its production, processing and trade remains a highly distinctive economic sector. 17 BIBLIOGRAPHY Allen, D.W., and D. Lueck. 2002. The nature of the farm: Contracts, risks, and organization in agriculture. Cambridge and London: The MIT Press. Binswanger, H.P., K. Deininger, and G. Feder (1995) Power, Distortions, Revolt and Reform in Agricultural Land Relations, ed. J. Behrman, and T.N. Srinivasan, vol. 3B. Handbook in Development Economics. Amsterdam, Elsevier. Binswanger, H.P., and M.R. Rosenzweig. 1986. "Behavioral and Material Determinants of Production Relations in Agriculture." Journal of Development Studies 22(3):503-539. Birthal, P.S., P.K. Joshi, and A. Gulati. (2005) "Vertical coordination in high value commodities: implications for the smallholders." Washington, DC, IFPRI, 85. Dannson, A., C. Ezedinma, T.R. Wambua, B. Bashasha, J. Kirsten, and K. Sartorius. (2004) "Strengthening farm-agribusiness linkages in Africa. Summary results of five country studies in Ghana, Nigeria, Kenya, Uganda and South Africa." Rome, FAO, 6. Dolan, C., and J. Humphrey. 2000. "Governance and Trade in Fresh Vegetables: The Impact of UK Supermarkets on the African Horticulture Industry " Journal of Development Studies 37(2 ):147 - 176 Dorward, A., J. Kydd, and C. Poulton, eds. 1998. Smallholder cash crop production under market liberalisation: A new institutional economics perspective Wallingford: CAB International. ---. (2006) "Traditional Domestic Markets and Marketing Systems for Agricultural Products." Background Paper for the World Development Report 2008. The World Bank. Dries, L., and J.F.M. Swinnen. 2004. "Foreign Direct Investment, Vertical Integration, and Local Suppliers: Evidence from the Polish Dairy Sector." World Development 32(9):1525-1544. Eaton, C., and A.W. Shepherd. (2001) "Contract farming: Partnerships for growth." FAO Agricultural Services Bulletin. Rome, FAO, 145. Frank, S.D., and D.R. Henderson. 1992. "Transaction Costs as Determinants of Vertical Coordination in the U.S. Food Industries." American Journal of Agricultural Economics 74:941-950. Fulponi, L. (2007) The globalization of private standards and the agri-food system, ed. J.F.M. Swinnen. Global supply chains, standards and the poor. Wallingford, UK, CABI. Galizzi, G., and L. Venturini, eds. 1999. Vertical relationships and coordination in the food system. Heidelberg: Physica Verlag. Gereffi, G., J. Humphrey, and T. Sturgeon. 2005. "The governance of global value chains." Review of International Political Economy 12(1):78-104. Glover, D.J. (1994) Contract Farming and Commercialization of Agriculture inDeveloping Countries ed. J. von Braun, and E.T. Kennedy. Agricultural commercialization, economic development, and nutrition. Baltimore, MD, Johns Hopkins University Press for International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI). Glover, D.J., and K.C. Kusterer. 1990. Small farmers, big business: Contract farming and rural development. London: Macmillan. 18 Goodman, D., and M. Watts, eds. 1997. Globalising food: Agrarian questions and global restructruing. London and New York: Routledge. Hart, G. (1997) Multiple trajectories of rural industrialisation: An agrarian critique of industrial restructuring and the new institutionalism, ed. D. Goodman, and M. Watts. Globalising food: Agrarian questions and global restructruing. London and New York, Routledge. Henson, S., S. Jaffee, J. Cranfield, J. Blandon, and P. Siegel. (2008) "Linking African smallholders to high-value markets: practitioner perspectives on benefits, constraints, and interventions." Working Paper. World Bank, 4573. Hu, D., T. Reardon, S. Rozelle, P. Timmer, and H. Wang. 2004. "The Emergence of Supermarkets with Chinese Characteristics: Challenges and Opportunities for China's Agricultural Development." Development Policy Review 22(5):557-586. Huang, J., S. Rozelle, X. Dong, Y. Wu, H. Zhi, X. Niu, and Z. Huang. (2007) "Agrifood Sector Studies China: Restructuring agrifood markets in China - The horticulture sector " Part A meso-level study. London, Regoverning Market Program, IIED. Huang, J., Y. Wu, Z. Yang, S. Rozelle, J. Fabiosa, and F. Dong. 2010. "Farmer Participation, Processing, and the Rise of Dairy Production in Greater Beijing, P.R. China " Canadian Journal of Agricultural Economics (In press). Huang, J., Y. Wu, H. Zhi, and S. Rozelle. 2008. "Small holder incomes, food safety and producing, and marketing China's fruit." Review of Agricultural Economics 30(3):469-479. Hueth, B., E. Ligon, and C. Dimitri. 2007. "Agricultural Contracts: Data and Research Needs." American Journal of Agricultural Economics 89(5):1276-1281. Hueth, B., E. Ligon, S. Wolf, and S. Wu. 1999. "Incentive Instruments in Agricultural Contracts: Input Control, Monitoring, Quality Measurement, and Price Risk." Review of Agricultural Economics 21(2):374-389. ---. 1999. "Incentive Instruments in Agricultural Contracts: Input Control, Monitoring, Quality Measurement, and Price Risk,." Review of Agricultural Economics 21(2):374-389. Humphrey, J., N. McCulloch, and M. Ota. 2004. "The impact of European market changes on employment in the Kenyan horticulture sector." Journal of International Development 16(1): 63-80. IFAD. (2003) "Promoting Market Access for the rural poor in order to achieve the millennium development goals." Rome, IFAD, February 2003. Jaffee, S., and S. Henson (2005) Agro-food exports from developing countries: The challenges posed by stardards, ed. M.A. Aksoy, and J.C. Beghin. Global agricultural trade and developing countries, The World Bank. Jaffee, S., and J. Morton, eds. 1995. Marketing Africa's high-value foods: Comparative experiences of an emergent private sector. Iowa: Kendall/Hunt Publishing Jia, X., Y. Hu, G. Hendrikse, and J. Huang. 2010. "Centralization or Individualism: The decision rights in Farmer Cooperatives in China." Paper presented at "Institutions in Transition – Challenges for New Modes of Governance". June 16-18, IAMO Forum 2010 Halle (Saale), Germany. Joskow, P.L. (2005) Vertical Integration, ed. C. Menard, and M.M. Shirley. Handbook of New Institutional Economics. The Netherlands, Springer. 19 Key, N., and D. Runsten. 1999. "Contract Farming, Smallholders, and Rural Development in Latin America: The Organization of Agroprocessing Firms and the Scale of Outgrower Production." World Development 27(2):381-401. Lazzarini, S.G., G.J. Miller, and T.R. Zenger. 2004. "Order with Some Law: Complementarity versus Substitution of Formal and Informal Arrangements." Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization 20(2):261-298. Little, P.D. (1994) Contract farming and the development question, ed. P.D. Little, and M.J. Watts. Living under contract: Contract farming and agrarian transformation in Sub-Saharan Africa. Wisconsin, The University of Wisconsin Press. Little, P.D., and M.J. Watts, eds. 1994. Living under contract: Contract farming and agrarian transformation in Sub-Saharan Africa. Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin Press. Ménard, C. 2004. "The economics of hybrid organizations." JITE 160(1):1-32. Ménard, C., and P.G. Klein. 2004. "Organizational Issues in the Agrifood Sector: Toward a Comparative Approach." American Journal of Agricultural Economics 86(3):750-755. Maertens, M., L. Colen, and J.F.M. Swinnen. (2008) "Globalization and poverty in Senegal: A worst case scenario?" LICOS Discussion Paper. Leuven, Belgium, LICOS Center for Institutions and Economic Performance, 199. Maertens, M., and Swinnen J. 2009. "Trade, Standards and Poverty: Evidence from Senegal." World Development, forthcoming. Martinez, S.W., and A. Reed. (1996) "From Farmers to Consumers; Vertical Coordination in the Food Industry." Washington, DC, ERS/USDA, AIB 720. Mighell, R.L., and L.A. Jones. (1963) "Vertical Coordination in Agriculture." Washington, DC, US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, Farm Economics Division. Minot, N. (2007) "Contract Farming in Developing Countries: Patterns, Impact, and Policy Implications." Ithaca, NY, Cornell University, Case Study #6-3. Minot, N.W. (1986) "Contract Farming and its effects on small farmers in less developed countries." East Lansing, MI, Michigan State University, Department of Agricultural Economics, 31. Miyata, S., N. Minot, and D. Hu. (2007) "Impact of contract farming on income: Linking small farmers, packers, and supermarket in China " MTID Discussion Paper. Washington D.C., International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), 00742. Perry, M.K. (1989) Vertical integration: Determinants and effects, ed. R. Schmalensee, and R.D. Willig, vol. 1. Handbook of Industrial Organization, Elsevier Science Publishers B.V. Poulton, C., A. Dorward, J. Kydd, N. Poole, and L. Smith (1998) A new institutional economics perspective on current policy debates, ed. A. Dorward, J. Kydd, and C. Poulton. Smallholder cash crop production under market liberalisation: A new institutional economics perspective Wallingford, CAB International. Poulton, C.D., A.R. Dorward, and J.G. Kydd (2005) The Future of Small Farms: New Directions for Services, Institutions and Intermediation. Imperial College, London. International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) & Overseas Development Institute. 20 Ravallion, M., and G. Datt. 2002. "Why has economic growth been more pro-poor in some states of India than others?" Journal of Development Economics 68(2):381-400. Reardon, T., and J.A. Berdegue. 2002. "The Rapid Rise of Supermarkets in Latin America: Challenges and Opportunities for Development." Development Policy Review 20(4):371-388. Royer, J.S., and R.T. Rogers, eds. 1998. The industrialization of agriculture. Vertical coordination in the U.S. food system. Aldershot: Ashgate. Shepherd, A.W. 2005. "The implications of supermarket development for horticultural farmers and traditional marketing systems in Asia (revised paper)." Paper presented at FAO/AFMA/FAMA Regional Workshop on the Growth of Supermarkets as Retailers of Fresh Produce. Kuala Lumpur, October 4-7, 2004. Simmons, P., P. Winters, and I. Patrick. 2005. "An analysis of contract farming in East Java, Bali, and Lombok, Indonesia." Agricultural Economics 33(s3):513-525. Start, D. 2001. "The Rise and Fall of the Rural Non-farm Economy: Poverty Impacts and Policy Options." Development Policy Review 19(4):491-506. Swinnen, J.F.M. (2007) The dynamics of vertical coordination in agri-food supply chains in transition countries, ed. J.F.M. Swinnen. Global supply chains, standards and the poor. Wallingford, UK, CABI. Swinnen, J.F.M., and M. Maertens. 2007. "Globalization, privatization, and vertical coordination in food value chains in developing and transition countries." Agricultural Economics 37(s1):89-102. Sykuta, M.E., and M.L. Cook. 2001. "A new institutional economics approach to contracts and cooperatives." American Journal of Agricultural Economics 83(5):1273-1279. WDR. (2008) "Agricultural for Development." World Development Report. The World Bank. Weatherspoon, D.D., and T. Reardon. 2003. "The Rise of Supermarkets in Africa: Implications for Agrifood Systems and the Rural Poor." Development Policy Review 21(3):333-355. Williamson, O.E. 1985. The economic institutions of capitalism. New York: The Free Press. ---. 1971. "The Vertical Integration of Production: Market Failure Considerations." American Economic Review 61(2):112-123. Wolf, S., B. Hueth, and E. Ligon. 2001. "Policing Mechanisms in Agricultural Contracts." Rural Sociology 66(3):359-381. World Bank, T. 2007. World Development Report 2008: Agriculture for Development. Washington, DC: The World Bank. WorldBank. (2006) "China's compliance with food safety requirements for fruits and vegetables: Promoting food safety, competitiveness, and poverty reduction." Report. The World Bank, 39766. Zylbersztajn, D., and E.M.M.Q. Farina. 1999. "Strictly coordinated food-systems: exploring the limits of the coasian firm." International Food and Agribusiness Management Review 2(2):249-265. 21 Figure. Determinants of contract farming Technology Techo-Economic Attributes of Commodity Uncertainty Asset Specificity Complexity Institutional Environment and the State Sectoral Structure Transactional Attributes Territorial Environment Institutional Environment Infrastructural Environment Bargaining Power Source: Adapted from Poulton et al. (1998) and Williamson (1985) Governance Contractual Arrangements -Form -Terms