draft of a working paper for education at brown university

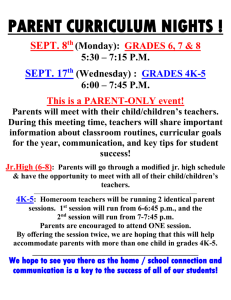

advertisement