Camera Obscura

advertisement

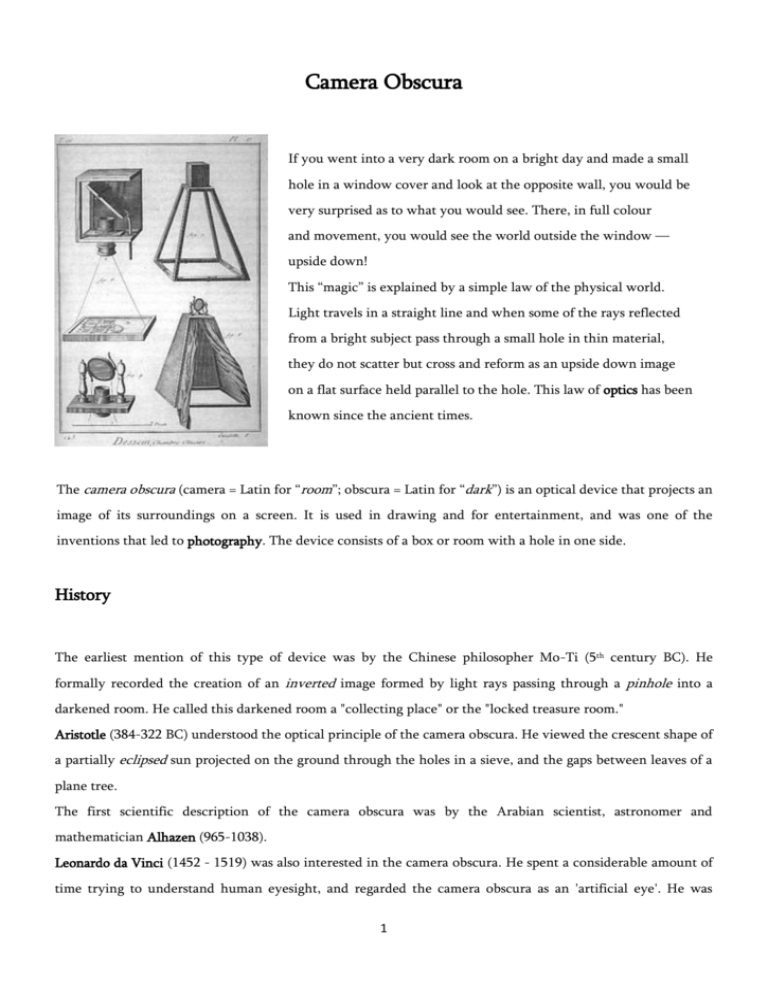

Camera Obscura If you went into a very dark room on a bright day and made a small hole in a window cover and look at the opposite wall, you would be very surprised as to what you would see. There, in full colour and movement, you would see the world outside the window — upside down! This “magic” is explained by a simple law of the physical world. Light travels in a straight line and when some of the rays reflected from a bright subject pass through a small hole in thin material, they do not scatter but cross and reform as an upside down image on a flat surface held parallel to the hole. This law of optics has been known since the ancient times. The camera obscura (camera = Latin for “room”; obscura = Latin for “dark”) is an optical device that projects an image of its surroundings on a screen. It is used in drawing and for entertainment, and was one of the inventions that led to photography. The device consists of a box or room with a hole in one side. History The earliest mention of this type of device was by the Chinese philosopher Mo-Ti (5th century BC). He formally recorded the creation of an inverted image formed by light rays passing through a pinhole into a darkened room. He called this darkened room a "collecting place" or the "locked treasure room." Aristotle (384-322 BC) understood the optical principle of the camera obscura. He viewed the crescent shape of a partially eclipsed sun projected on the ground through the holes in a sieve, and the gaps between leaves of a plane tree. The first scientific description of the camera obscura was by the Arabian scientist, astronomer and mathematician Alhazen (965-1038). Leonardo da Vinci (1452 - 1519) was also interested in the camera obscura. He spent a considerable amount of time trying to understand human eyesight, and regarded the camera obscura as an 'artificial eye'. He was 1 particularly perturbed by the fact that the image in the camera obscura was inverted, for this suggested that this occurred also in the human eye. The image quality was improved with the addition of a convex lens into the aperture in the 16th century and the later addition of a mirror to reflect the image down onto a viewing surface. The term "camera obscura" was first used by the German astronomer Johannes Kepler in the early 17th century. He used it for astronomical applications and had a portable tent camera for surveying in Upper Austria. Development and application The artists have long aspired to being able to paint pictures with accurate perspective to create a threedimensional scene. Camera obscura enabled them to do precisely that. In essence, by hanging a canvas on the opposite wall to the lens of a camera obscura, one can faithfully reproduce the image! Many artists, such as the 17th century Dutch Masters, particularly Johannes Vermeer, were known for their magnificent attention to detail. It has been widely speculated that they made use of such a camera, but the extent of their use by artists at this period remains a matter of considerable controversy. Early camera obscura models were large, comprising either a whole darkened room or a tent. By the 18th century more easily portable models became available. These were extensively used by amateur artists while on their travels, but they were also employed by professionals. The final development of the camera obscura was as a mass entertainment medium. Large 'cameras' holding some 10-15 persons were built (often at seaside holiday resorts and outdoor places of entertainment, amusement parks and the like) and the image, transferred from the tower-sited lens arrangement, was projected onto a large circular 'table like' 'screen' around which an 'audience' could gather. Being 'live' the image was in colour and it moved and certainly a 'pre' cinema experience in the late 1800's. Today the camera obscura is enjoying a revival of interest. Older camera obscuras are celebrated as cultural and historic treasures and new camera obscuras are being built around the world. 2