This handbook refers to the MA course in Creative and Critical

advertisement

MA in Creative and Critical

Writing

Handbook 2014-15

This handbook refers to the MA course in Creative and Critical Writing offered by the School of

English at the University of Sussex

The convenor of this course is Professor Nicholas Royle, N.W.O.Royle@sussex.ac.uk

1. Introduction

The MA in Creative and Critical Writing at Sussex has developed out of longstanding teaching

and research interests in creative writing as well as in psychoanalysis, cultural materialism, ecopoetics, postcolonialism, deconstruction, feminism and queer theory.

This MA is designed to enable students to combine an interest in intellectually challenging

critical and theoretical ideas with an interest in creative writing. It is based on the supposition

that ‘theory’ and ‘practice’ are not opposites, though the relations between them may entail

productive tensions and paradoxes. It is impelled rather by the sense that the critical and the

creative are necessarily intertwined. Many great writers in English, at least since Milton, have

also written important criticism. Good writers are invariably also good readers.

The MA in Creative and Critical Writing offers students modules that combine ‘theory’ and

‘practice’, focusing on critical writings, for example, specifically with a view to encouraging and

clarifying a sense of how to write creatively and well, and how to think creatively and differently

about the possibilities of writing. Hélène Cixous is Honorary Professor of the Creative and

Critical Writing Course at Sussex; J. H. Prynne is Visiting Professor. Among the special features

of this MA course is a creative and critical writing workshop (running weekly through the Autumn

and Spring terms) specifically for those studying on the course.

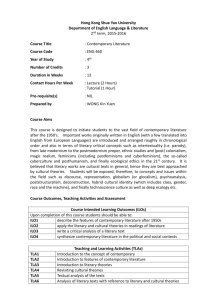

2. Course structure and specifications

For full-time students the course comprises four taught 12 week modules, two in the Autumn

and two in the Spring, together with a weekly creative and critical writing workshop that runs

through the Autumn and Spring terms. This is followed by the preparation and writing of a

dissertation under supervision. Modules are normally taught by weekly seminar.

Each module attracts 30 credits and the Dissertation 60 credits: the total number of credits

constituting the course is 180. Details regarding term papers and dissertations are given in the

general Postgraduate Handbook and information sessions are also arranged by the Graduate

Centre Directors.

Each module is examined by a 5000-word term paper, to be submitted at the beginning of the

term following that in which the module is taught. The dissertation length is 15,000 words and it

is submitted at the start of September.

For part-time students, the same requirements are spread over two years, with one module

taken in each of the successive Autumn and Spring terms, and with the preparation and writing

of the dissertation extended over two summer periods. Part-time students also have the

opportunity to attend the workshops throughout the two years (Autumn and Spring terms).

In the Autumn and Spring terms CCW students are invited to attend reading and performance

events which take place at regular intervals. There are numerous opportunities to hear and

meet practising writers from outside Sussex, as well as (on occasion) publishers and literary

agents. Creative and Critical Writing Students also have the chance to present their own work in

this context. Students are also encouraged to attend other open seminars run by the English

Department and indeed elsewhere in the Humanities.

This year, the modules constituting the course are as follows:

Autumn Term

Psychoanalysis and Creative Writing

Deconstruction and Creative Writing

Creativity and Utopia

Spring Term

Marxism and Creative Writing

Voices in the Archives: Writing from History

The Migrant Writer

Experimental Writing

3. Course learning outcomes

A student who has completed the MA in Creative and Critical Writing successfully

should be able to:

demonstrate an ability to produce creative work stimulated and inflected by an encounter

with issues in contemporary critical thinking and writing

demonstrate an ability to produce critical work stimulated and inflected by experience

and practice in creative writing

demonstrate a specialised knowledge of selected key issues in the field of creative and

critical writing;

demonstrate a detailed knowledge of one or more leading topics in contemporary critical

thinking;

demonstrate oral and writing skills in which a clear, concise and exact use of language is

brought to bear on a rigorous consideration of texts, ideas and controversies within the

field;

demonstrate an ability to understand and to use, when necessary, some of the specialist

vocabularies associated with literary criticism and theory;

cite relevant materials judiciously, and to good effect, in the construction of an overarching argument;

read ‘literary’, ‘historical’ and ‘theoretical’ texts critically and attentively;

demonstrate skill in time and work management, including the ability to read, write and

research independently

use electronic resources;

put together well-presented and well-edited creative work and well-written, fullyreferenced, word-processed critical essays;

carry out a substantial and original piece of research within the field.

essays.

4. Course modules

Autumn Term:

Psychoanalysis and Creative Writing:

Psychoanalysis has exciting and major implications for all kinds of writing, not least that sort

called ‘creative’. This module will focus on some of the ways in which a close reading of

psychoanalytic texts, especially those of Sigmund Freud himself, can be linked to the theory and

practice of creative writing. We will look in particular detail at how Freud’s work illuminates the

question of literature (and vice versa) in relation to such topics as the uncanny, fantasy and daydreaming, story-telling and the death drive, chance, humour, mourning and loss. Concentrating

on detailed reading and discussion of a series of psychoanalytic, critical and literary texts, the

module will lead students through to having an opportunity to submit a term-paper work that

may include a creative writing as well as a critical component.

Deconstruction and Creative Writing:

This course focuses on deconstruction, especially in relation to the work of Jacques Derrida,

and on the theory and practice of creative writing. Following a preliminary discussion of the

question ‘what is deconstruction?’, we will explore a series of topics including the gift, madness,

secrets and drugs. There will be texts by Kafka, Borges, Katherine Mansfield, Blanchot and

Harry Mathews, for example, as well as work by Derrida and Cixous. Concentrating on detailed

reading and discussion of a range of deconstructive, critical and literary texts, the course will

lead students through to having an opportunity to submit a term-paper that can (if the student

wishes) include a creative writing as well as a critical component.

Creativity and Utopia:

This module explores the intimate relationship between creativity and utopia, as it is played out

in literary and theoretical texts from More to the present day. It examines the extent to which

the art work can create new worlds (brave or otherwise), and traces the historical changes in the

utopian function of literature, in its various philosophical, literary and theoretical manifestations.

After an initial grounding in More's Utopia, the module moves through some key eighteenth and

nineteenth century utopias, before focusing on the ways in which utopian thought is refashioned

in modernist and contemporary writing. In paying attention to the changing function of utopian

thinking in twentieth century literature, the module also explores how the theoretical

developments of the modern and contemporary period have inherited a utopian legacy. How

has Marxist utopian thinking informed modern and contemporary utopianism? How does the

Frankfurt school investment in utopian thought relate to Derridean and Deleuzian conceptions of

utopian possibility? The relationship between creativity and utopia will be explored both through

the reading of several key utopian texts, and through reflections on the practice of creative

writing.

Spring Term:

Marxism and Creative Writing:

In the wake of the end of the Cold War and especially since ‘September 11’, as

neoconservatives replaced Marxism with ‘terrorism’ as their new and irrational enemy, many

writers in America and Europe sought with redoubled commitment to revitalise elements of

Marxist thinking in their creative practice: to confront the new dominant form of rationality with a

creative rationality of the dominated. This module will investigate the history and present

significance of that commitment in several ways: through study of the tradition of Marxist

thinking about the relation of aesthetics to social and political life; through consideration of

mainstream trends in contemporary literature and the economic and political interests they

reflect and fortify; and through the evaluation of theoretical claims made by contemporary

writers themselves, both in creative writing and in criticism, about their own strategies of

opposition and the problem of their potential efficacy. Students will be asked to reflect on the

significance of these problems for their own creative and critical practice.

Voices in the Archives: Writing from History:

This module invites you to consider the ways creative writing uses history, from pragmatic

research strategies to theoretical implications. We think about how different literary genres

engage with the past through form, narrative and literary language, looking at the cultural impact

of contemporary historical fiction, and also considering work by poets and film-makers. Authors

studied may include Sarah Waters, Ian McEwan, Toni Morrison, Hilary Mantel, David

Dabydeen, Mario Petrucci, George Szirtes and Michel Hazanavicius. Creative workshops

introduce key research skills, exploring the methodological implications of using physical and

virtual archives. Working with historical newspapers, letters, diaries, prints, photographs and

other documents, we immerse ourselves in old-fangled vocabularies, and experiment with using

language from the past to inflect our contemporary voices. Topics for discussion include the

critical and ethical implications of writing about real historical events and characters. We

consider how contemporary writing is founded on a long tradition of writing from history - often

re-visiting the past with a particular political or creative agenda - from Shakespeare and Dickens

onwards. Additionally, we explore how recent historical fiction interacts with other genres, for

example in the fantasies of Susanna Clarke and Angela Carter. We consider theoretical work on

memory and nostalgia by critics such as Mieke Bal and Svetlana Boym.

Experimental Writing:

This module considers why and how writers produce new forms. It explores the historical and

current uses of a variety of names for writing that defies generic expectations ('innovative,'

'avant-garde,' 'experimental,' 'difficult,' and 'cross-genre,' to name a few). The module will

require that students read a wide range of exemplary texts (likely but not necessarily chosen

from the modern and contemporary periods) that eschew easy generic categorisation. A

particular theme or problem may be selected by the tutor each year (e.g., cross-genre writing,

innovative poetics, documentary writing, speculative fiction). Readings might include work by

Walter Benjamin, Andrea Brady, Anne Carson, Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, Renee Gladman,

Bernadette Mayer, Fred Moten, Harryette Mullen, Maggie Nelson, Raymond Queneau, Charles

Resnikoff, Sophie Robinson, Fran Ross, Muriel Rukeyser, Monique Wittig. Critical inquiry will

focus on the effects of formal techniques within specific literary historical and social contexts.

Students will also develop their own writing, and up to 50% of class time may be devoted to

workshopping student work. As writers, students may be asked to identify the tensions or

contradictions that animate their writing and to work up, in structured, experimental, or

procedural fashion, a set of formal mechanisms for reframing these tensions. The module will

help students to bring creative writing and critical practice together in order best to navigate their

aims and objectives for writing. Final assessment will involve a critical/creative dissertation of

6,000 words.

The Migrant Writer: Postcolonialism and Creativity:

‘To write…is to travel’, according to Iain Chambers; the module will use this idea to explore the

displacement of the writing subject within the historical context postcolonial migration. The work

of key immigrant writers will be analysed in relation to central concepts in literary and cultural

criticism: hybridity and dialogical discourse, the development of ‘border languages’, mimicry

and the migrant subject, homelessness and the creation of new cartographies, and diasporic

and non-originary histories. In the process the centrality of migration, exile and displacement to

a range of critical and theoretical approaches will be highlighted.

5. Teaching and learning

Depending on where you were an undergraduate, you may find that you have either fewer or

more teaching hours as an MA student than you did when you were studying for your BA. Fulltime students will normally be doing two modules at any one time (plus the writing workshop):

each of these will involve a weekly seminar of just under two hours. You are also strongly

encouraged to attend The Wing, plus any other relevant open seminars that are brought to your

attention. In addition, you should spend at least 15 hours a week in individual study. The

University and the School of Humanities provide certain facilities and resources – most notably,

a library, the use of computers, and a space where learning is constantly pursued. Your tutors

will direct your study with reading lists and all kinds of informal advice. Your ideas and

conclusions will be put to the test in seminars, where you will be expected to have reached

some views of your own and to be able to argue for them. Your written work will be formally

assessed to determine your degree result, and you will receive feedback on your term papers

as you go along. We will help you as much as we can, but what you get out of your study will

depend on how much you put into it: your mastery of the subject is primarily something for you

to achieve. Though the structures we put in place will assist you in this endeavour, they cannot

do the work for you.

Individual Study

The largest, and in many ways the most important, part of your working time will be spent on

your own, or discussing problems with your fellow-students. It is important to organise your time

effectively, and to plan your use of the library, especially if you have to do paid work as well as

your academic work. A word of advice: always set yourself specific and realistic targets when

you work, and take regular breaks. Set yourself to read a particular article or chapter of a book,

or to work for a pre-determined length of time (say one and a half hours) and then pause when

you have completed this task. A few periods of intense concentration, separated by short

breaks, will serve you far better than any amount of time spent sitting at a desk but not really

concentrating.

Module seminars

The focus of your work for each module will be a weekly seminar. You should be in command of

the reading set, and be prepared to try out your own ideas and to defend them in discussion.

Module seminars are compulsory. In many seminars, some form of presentation will also be

required: your tutor will give you guidance on the form which presentations are expected to take

and how to prepare them.

Training sessions

The Graduate Centre in Humanities organises several training sessions for all MA students in

the Humanities in the course of the year, on generic topics like ‘writing a term paper’ and ‘writing

a dissertation’. These sessions will be advertised to you in advance and we strongly advise you

to attend them. Fuller details are given in the Graduate Centre in the Humanities Postgraduate

Handbook.

Essays

We require that your essays be professionally presented: typed or word-processed, with full

scholarly references and a bibliography. Pay particular attention to matters of spelling, style and

punctuation. Poor punctuation is one of the commonest failings in student essays, even at

graduate level. If you are unsure about correct punctuation, get hold of a guide: there are

several cheap and readable such guides on the market.

You can find further information about how to research and write term papers and dissertations

at http://www.sussex.ac.uk/cssd/info_for_MA_students/index.shtml.

Module Evaluation

Student evaluation forms are issued at the end of each module and are scrutinised by the tutors

associated with the module before it is taught again. These forms are anonymous, and are an

opportunity for you to tell us what you felt about all aspects of the module, including the material

covered, teaching methods, and the adequacy of library and web resources. We take your

comments and suggestions for improvement very seriously. We do not, of course, guarantee to

be able to meet all student requests, first because we have to operate within tight financial

constraints, and second because we have to exercise our own academic judgement about the

desirability of any change. In addition, some key areas – notably the library – are beyond the

immediate control of the Graduate Centre. But we do guarantee to give active consideration to

all serious suggestions for change and improvement.

6. Assessment Criteria

Band

Distinction

Percentage

70-100%

Variation

80-100%

70-80%

Merit

60-69%

Qualities

Truly exceptional work that could be published with

little or no further development or alteration on the

strength of its original contribution to the field, its

flawless or compelling prose, its uncommon

brilliance in argument and its demonstration of

considerable knowledge of the topics and authors

treated on the module.

Outstanding work that might be fit for publication

or for development into a publishable article. Work

that is exceptional for its originality of conception

and argument, its conduct of analysis and

description, its use of research and its

demonstration of knowledge of the field and of the

core materials studied on the module.

Good or very good work that is thoughtfully

structured or designed, persuasively written and

argued, based on convincing use of research and

fairly original in at least some of its conclusions.

Pass

50-59%

Fail

0-49%

Satisfactory work that meets the requirements of

the module and sets out a plausible argument

based on some reading and research but that may

also include errors, poor writing, or some unargued

and improbable judgments.

35-49%

Unsatisfactory

Work that is inadequate with respect to its

argument, its use and presentation of research and

its demonstration of knowledge of the topics and

authors treated on the module, or that is poorly

written and difficult to follow or understand.

15-34%

Very

unsatisfactory

Work that plainly does not meet the requirements

of the course and that fails to make any persuasive

use of research or to conduct any argument with

clarity or purpose.

0-15%

Unacceptable or not submitted.

7. Teaching faculty

Peter Boxall (English) has published widely on modern and contemporary writing. Recent

books include Twenty-First Century Fiction: A Critical Introduction, Don DeLillo: The Possibility

of Fiction, Since Beckett: Contemporary Writing in the Wake of Modernism and an edition of

Beckett's novel Malone Dies. He is currently editing a volume of the Oxford History of the Novel

with Bryan Cheyette. He is the editor of the UK journal Textual Practice.

Nicholas Royle (English) works in the fields of modern literature and literary theory, as well as

Shakespeare. His books include Veering: A Theory of Literature, How to Read Shakespeare,

The Uncanny, E.M. Forster, Jacques Derrida, Telepathy and Literature and (with Andrew

Bennett) An Introduction to Literature, Criticism and Theory. He is an editor of the Oxford

Literary Review. He has also published numerous works of short fiction, as well as a novel,

Quilt.

Minoli Salgado (English) works on postcolonial literature and theory, as well as

poststructuralist debates in history. She is the author of the critical study Writing Sri Lanka; her

short fiction and poetry have been published internationally.

Sam Solomon (English) works broadly on twentieth century and contemporary literature

(poetry and cross-genre writing especially) as they relate to radical social movements; he has

written on the connections of gay and women's liberation to political economy, particularly in the

context of Marxist-feminist praxis. Research and teaching interests include: creative writing,

feminism, Marxism, contemporary poetics, cross-genre and documentary writing, queer theory,

critical university studies, Yiddish literature and culture, literary translation, aesthetics and

politics.

Bethan Stevens (English) has research interests which involve people and groups whose

work crosses over between the visual and the literary, such as William Blake; the Flaxmans (an

eighteenth-century family including an RA sculptor, book-illustrator and amateur writer);

eighteenth- and nineteenth-century producers of chapbooks and illustrated novels; the PreRaphaelites; Virginia Woolf and Vanessa Bell.

Keston Sutherland (English) works on 20th century and contemporary poetry; Marx, the

reception and translation of Marx, and Marxism; Adorno; Wordsworth; Pope; Beckett. Recent

books include TL61P, a suite of five greater odes dedicated to the now-obsolete product code

for a Hotpoint tumble and spin dryer, Stupefaction: a radical anatomy of phantoms, The Stats on

Infinity, Stress Position and Hot White Andy. He is the editor of Quid, Brighton's chief organ of

neopreraphaelite totalitarian poetics, and co-editor of Barque Press. He is currently working in

scholarly fashion on the poetics of Marx's critique of political economy, on the problem how

perfection may be disgusting, and on mouths.

![MA in Creative and Critical Writing Course Handbook 2015-16 [DOC 1004.00KB]](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/015093854_1-3b74976a6e091fb24ee673c19017fb58-300x300.png)