Report

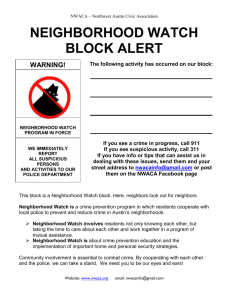

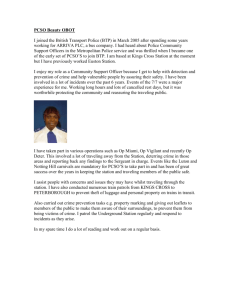

advertisement