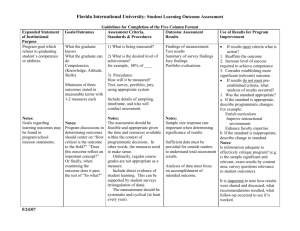

Issues Paper - Department of Justice

advertisement