Human Needs: Overview

advertisement

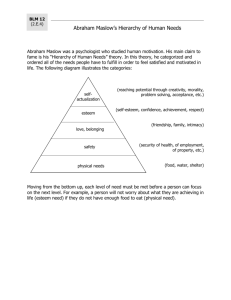

Human Needs: Overview Michael A. Dover and Barbara Hunter-Randall Joseph Abstract Human need is a central theme for social work, yet has been both a neglected and contested concept. Moralistic views of need prevailed in social work’s early years. More recently, needs concepts have influenced social work education, practice, research and ethics as well as social welfare policy and social action. Human needs theory, along with conceptions of human rights and social justice, provide a strong conceptual basis for social work. Keywords: human needs; human rights; social justice; needs assessment; basic needs; empowerment The notion of human need recognizes a central aspect of the human condition. Human need is both a neglected and a contested concept, one which has been invoked in social work’s calls for social reform but has rarely been central to our practice models or social welfare policy development and analysis (Timms & Timms, 1977). Human need has been seen as empowering, in that it leads to demands for human rights (Wronka, 1992), but also as humiliating, in that it can subject those with unmet needs to negative, stigmatized, minimal definitions of need by those with power (Illich, 1978). The concept of human need goes to the heart of rational human development, since it draws its imperative from each person’s intuitive understanding of the requirements for individual survival. Although at the societal level human needs have often been obfuscated, the concept of human need is an important foundation for social work practice and societal social policy. History of Usage of Needs Concepts in Social Work According to one study of the proceedings of the National Conference of Charities and Corrections, covering the early development of social work through 1914, no unified concept of need was ever defined (Joseph, 1975). References to need were transformed into needy, neediness and needful or “in need,” or replaced with associated terms such as requirements, necessaries, human nature, problems, rights, poverty, standard of living, living wage, and relief. The marriage of need to relief may have impeded the development of the concept. According to 21 the prevalent moralistic view of the time, need was an evil which had to be resisted even in the face of terrible suffering. What the poor needed more than relief was spiritual uplift. Edward Devine stressed service needs rather than human needs (Devine, 1909). He also warned not to make possibly erroneous assumptions about human nature. Such lack of confidence in the veracity of theories of human needs has produced an ongoing ambivalence towards the use of needs concepts in social work. Another source of social work’s ambivalence towards needs may be that it brought to mind the famous slogan, “From each according to his abilities, to each according to his needs!” (Marx, 1978). For instance, Devine made sure to note that some needs could be met within the present system, without being revolutionary (Devine, 1909). During the McCarthy period, the plates to Towle’s book Common Human Needs were destroyed in 1951 by the federal government after criticism by American Medical Association officials (Posner, 1995; Towle, 1965[1945]). The book was reissued by the AASW in 1952 and again in 1957 by NASW and remains in print today. Needs concepts including basic human nutritional requirements were advanced in early 20th century England (Booth, 1902; Rowntree, 1902; Webb & Webb, 1927). This early work influenced England’s subsequent social welfare theorists (Bradshaw, 1972; Titmuss, 1968). In times of crisis, human consciousness about human need increases (Joseph, 1975; Wronka, 1992). Often, recognition of universal needs evolves from relief efforts during disasters and epidemics that affect every one across class and color lines. During the 1950s, international attention turned to issues of human need. McHale and McHale cited a 1954 UN report on measures and standards of living (McHale & McHale, 1978; United Nations, 1954), and conceptualized a set of psychophysical and psychosocial needs amenable to cross-national comparative research (McHale & McHale, 1979). For some time during the 1970s and 1980s, U.S. international development policy was guided by what was known as the basic needs model (Moon, 1991; Sartorius & Ruttan, 1989). Declarations of need were the foundation of rights statements such as the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights and Article 25 of the International Declaration of Human Rights (Reichert, 2003). A review of theoretical and empirical work on needs by social workers shows a rich history albeit a masked one seemingly relegated as a central concept to a few books (Thursz & Vigilante, 1975; Towle, 1965[1945]), a limited number of journal articles (Posner, 1995; Vigilante & Mailick, 1988), brief sections in social work textbooks, and three social work dissertations (Hage-Yehia, 1983; Joseph, 1986a; Steiner, 1986). Nevertheless, Wilensky and 21 Lebeaux argued that an integrative view of human needs was a requirement of any advanced social welfare system (Wilensky & Lebeaux, 1958). Theories of Human Need For decades, the main needs-related theories used in social work were the theories of Abraham Maslow, Erich Fromm, and Henry Murray (Allen-Meares, 1987; Fromm, 1955; Maslow, 1943; Murray, 1938). Maslow’s hierarchical theory of human need (physiological, safety, belonging/love, self-actualization) was later amended to include self-transcendence, although few texts reflect this (Koltko-Rivera, 2006; Maslow, 1969, 1971). Maslow’s theory has been subjected to widespread criticism for not being grounded in empirical research and for being a value-laden hierarchical list, rather than a theory constructed using philosophically rigorous methods (Cofer, 1986; Springborg, 1981). However, some important approaches to human needs arose from within social work in the United States (Vasey, 1958; Wolins, 1967). Gil viewed human needs as including the following interrelated dimensions: Social/psychological needs for meaningful human relationships of the “I-Thou” type (Buber, 1937); productive/creative needs such as meaningful work; security needs derived from trust that the earlier-mentioned needs have been met; self-actualization needs, citing Maslow’s updated edition (Maslow, 1970); spiritual needs (Gil, 1976, 1984, 1992, 1998, 2004). Concurrently with these developments within social work, feminist and Marxist and neo-Marxist contributions tackled the concept of need (Fraser, 1998; Heller, 1976; Hughes, 2000; Soper, 1981). Since 1987 a number of monographs have appeared that focus squarely on human needs (Braybrooke, 1987; Hamilton, 2003; Reader, 2007). Recently, Noonan has asserted the primacy of needs-based concepts in moral philosophy and ethics (Noonan, 2002, 2004, 2006). In addition, a number of edited collections on human needs appeared (Brock, 1998; Reader, 2005; Taylor, 2006). In A Theory of Human Need, Len Doyal and Ian Gough presented a theory that views civil, political and women’s rights as a precondition for the development of culturally embedded methods of satisfying intermediate needs, including food, water, housing, nonhazardous work, and physical environment; appropriate health care; security in childhood; significant primary relationships; economic security; safe birth control and child-bearing, and basic education (Doyal & Gough, 1991; Gough, 2000a). Those intermediate needs, in turn, must at least be 21 satisfied at a minimally optimal level in order to meet two primary basic needs, physical health and autonomy of agency. These two needs must be met in order to avoid serious harm and engage in social participation. (Doyal, 1998; Doyal & Gough, 1991). The theory built on Rawls’ original position approach and its specification of various specific democratic rights seen as logically as necessary for protection against harm, given the distinct possibility, under the veil of ignorance, that one might need such rights (Rawls, 1971). Social Work Education Early on, it was recognized that teaching about human need should be an integral part of social work education (Bisno, 1952; Boehm, 1956; Stroup, 1953). However, debates arose over how central needs concepts should be for social work. Lee criticized hierarchies of need and contended that needs were unique within different societies (Lee, 1948, 1959). Boehm argued that human needs were both universal and culturally specific, but concluded that social work’s focus should be on human social functioning and societal level resource distribution (Boehm, 1958). Kahn also criticized the confusion regarding the nature of human needs (Kahn, 1959). Although Maslow had warned that field theory should not be a substitute for needs theory, Hearn relied on Lewin’s field theory to develop general systems theory, which became the foundation of social work education’s ecosystems perspective (Hearn, 1979; Lewin, 1947; Maslow, 1943). Despite calls for needs content in social work education (Blake, 1994; Jones & Pandey, 1977), very little actual curriculum content has addressed human needs concepts, with the exception of brief coverage of Maslow’s work (Maslow, 1970). However, CSWE’s current Educational Policy and Accreditation Standards included the following statement about the purposes of social work education (Council on Social Work Education, 2004, p. 4): “To formulate and implement social policies, services, and programs that meet basic human needs and support the development of human capacities.” Social Welfare Policy Needs concepts have been most strongly represented in contributions to social welfare policy and social policy analysis. In Unravelling Social Policy, Gil pioneered proposals for making human needs central to social policy (Gil, 1992). Gil said that the level of human needs attainment depended upon the structures, dynamics, and values of the social order (Gil, 1984). 21 Other authors viewed human needs concepts as key to understanding social problems (Herman, 1978), housing and employment problems (Mulroy & Ewalt, 1996; Swartz, 1995), and the nature of poverty (Spicker, 2007). Robertson’s overview of the politics of human needs in the modern welfare state stressed the value of human needs concepts in providing a countervailing discourse to the domination of market principles (Robertson, 1998). There has been substantial debate about the degree to which human needs can be met within capitalist societies (Dokecki, 1985; Gough, 2000a; Warshawsky, 1985). For instance, although Nixon argued that there were built-in limitations on meeting human needs under monopoly capitalism (Nixon, 1971), others opposed taking a defeatist position towards the meeting of human needs under capitalism and suggested that radical reforms could meet working class and community needs (Dover, 1992; Olson, 1982). Human needs concepts, others add, could contribute to a strengths-based approach to social policy (Chapin, 1995), and are seen as central to theories of human rights (Wronka, 2008). Mullaly saw universal human needs and the culturally specific ways in which they are met as essential to the emancipatory mission of social work (Mullaly, 2001). Social Work Practice Needs concepts have frequently been utilized in the literature on social work practice, but were not central to any identified practice model. Richmond considered individual needs and community needs within the larger social environment (Richmond, 1922). Robinson embraced relativism with respect to need, and shifted the unit of attention from individual need to the worker–client relationship itself (Robinson, 1930). Hamilton saw psychological needs as culturally differentiated, and viewed need as an issue for eligibility (Hamilton, 1951). Reynolds expressed concern that the new focus on relationship and on the identification of client wants rather than needs carried with it the danger of unclear social worker responsibility for the outcome of work with clients (Reynolds, 1934). Later, Reid criticized a social work role in prescribing solutions for attributed needs (externally defined needs), rather than acknowledged wants (Reid, 1978). The Life Model of practice was concerned that social work tended to try to fit people’s needs into the method of service being used (Germain & Gitterman, 1980). Goodness-of-fit takes place between life tasks, needs, and goals on the one hand, and stimuli and resources on the other (Germain & Gitterman, 1979). 21 Needs concepts were seen by some as important for social work practice (Gil, 1978). Culturally informed social work practice was seen as essential to meeting basic human needs (Applewhite, 1998; Schiele, 1997). Joseph contended that human needs provide a key framework for community organizing practice, which may include efforts to restructure our society in order to distribute resources in a just and equitable basis in order to meet human needs (Joseph, 1986b). Conway stressed the importance of people’s spiritual needs as a focus for practice (Conway, 2005). Briar called for a more integrative response to human need (Briar, 1985). The Doyal–Gough theory of human need was seen as valuable for need-based practice models, needs assessment, and policy analysis (Dover, 1993). The strengths-based model of practice stressed that social workers focus on the assets of clients. This model reflected concern that needs talk can reinforce stigmatizing clients as needy, which could in turn lead to the disempowerment of clients (Saleebey, 2006). Arguably, however, the strengths perspective’s focus on human capabilities is fully consistent with the use of the capabilities concept in human needs theory (Alkire, 2005; Gough, 2003, 2004; Nussbaum, 2000; Sen, 1985). Also, human need was seen as an important concept guiding empowerment based practice (Cox & Joseph, 1998; Gutiérrez, Parsons, & Cox, 1998). Social Research Human needs theory has been used in needs assessment research (Percy-Smith, 1996), crossnational comparative social welfare research (Gough, 2000b), and research on human wellbeing (Clarke, Islam, & Paech, 2006; Costanza et al., 2007; Gough & McGregor, 2007). Maslow’s hierarchy of needs has been used to study palliative care (Zalenski & Raspa, 2006), children in crisis (Harper, Harper, & Stills, 2003), homelessness (Sumerlin & Norman, 1992), and other topics. Maslow’s theory influenced the caregiver’s well-being scale (Berg-Weger, Rubio, & Tebb, 2000; Tebb, 1995). Operationalizations of the Doyal–Gough theory have been used for research on women’s health (McMunn, Bartley, & Kuh, 2006), risk and resilience in children (Little, Axford, & Morpeth, 2004), housing adaptations for persons with disabilities (Heywood, 2004), and community-based needs assessment (Percy-Smith & Sanderson, 1992). Common human needs can be reconciled with individual human differences and with cultural diversity via the utilization of both modern and postmodern frameworks (Guadalupe & Freeman, 1999; Mullaly, 2001). One study found that clients were more concerned with broadly conceived universal human needs, while providers were more focused on service needs 21 related to domestic violence, child abuse, and substance abuse (Darling, Hager, Stockdale, & Heckert, 2002). Social and Political Action Human needs concepts have strongly influenced social work’s approach to social and political action. Flower and Wagner reported on an example of political action focused on the human needs of poor and working people in Maine (Noble & Wagner, 2004). Olson called into question the extent of social work’s commitment to social justice as an organizing concept (Olson, 2007). Drawing upon Maslow, he viewed the meeting of physiological and safety needs as the foundation of economic justice. Furthermore, he contended that satisfying work, education, and cultural development would meet human needs for love of others and for selflove. He proposed a professional project for social work based upon such a needs-based conceptualization of social justice. Making social benefits a human right was also seen as essential for addressing common human needs (Abramovitz & Blau, 1984), and for building majoritarian coalitions aimed at meeting common human needs (Blau, 1992). Social Work Values and Ethics The 1958 Working Definition of Social Work stated, “There are human needs common to each person, yet each person is essentially unique and different from others” (Boehm, 1958). Kadushin’s inventory of professional knowledge and skills stated that social workers require knowledge of the nature of human needs that social welfare programs are designed to meet (Kadushin, 1959). Timms identified the meeting of common human needs as one of social work’s core values (Timms, 1983). The preamble of the Code of Ethics of NASW, as adopted in 1997, states: “The primary mission of the social work profession is to enhance human wellbeing and help meet the basic human needs of all people.” The inclusion of human needs content in the Code of Ethics and this first-time entry on Human Need in the Encyclopedia of Social Work show increased interest in human need theory in social work. Citing Towle’s Common Human Needs, Reamer pointed out that the concept of common human needs is well established in social work and reinforces our historic commitments to meeting basic needs and enhancing well-being (Reamer, 1998; Towle, 1965[1945]). Despite this use of human needs concepts in social work, Western values of individualism and the 21 influence of Freudian theory may have reduced the influence of human needs theory on social work (Galper, 1975; Lichtenberg, 1969). Needs, Rights, and Justice: Recent Theoretical Developments The relationship between human needs, human rights, and social justice has been the subject of a great deal of debate (Bay, 1988; Wringe, 2005). Gil, Witkin, and Wronka have all argued that human needs concepts are central to social justice and human rights (Gil, 2004; Witkin, 1998; Wronka, 1992). Wakefield utilized Braybrooke’s philosophy of needs in his work on the relationship of psychotherapy to social justice (Braybrooke, 1968; Wakefield, 1988). However, while human needs and human rights concepts are often seen as reinforcing each other, Noonan stressed the centrality of meeting human needs for the development of democratic societies. He pointed out that conceptualizations of rights often give primacy of place to property rights in a way which can inhibit the meeting of human needs (Noonan, 2005). Ife contended that social work should move beyond needs-based approaches and adopt rights-based practice, but still discuss rights related to needs and vice versa (Ife, 2001). One way of reconciling the vocabularies of needs and rights is to better conceptualize human obligations (Wringe, 2005). Wronka has pointed out that duties to the community are recognized in Article 29 of the International Declaration of Human Rights (Wronka, 1992). Amartya Sen pointed out in Development and Freedom that basic political and liberal rights are directly related to people’s social and political participation, and their ability to exercise their claim that their economic needs be respected (Sen, 1985). Political liberty and civil rights are essential if we are to better conceptualize our needs, including our economic needs (Sen, 1999). Despite these advances in theories of human need, debate continues about whether one can speak of universal human needs and rights. Future Trends and Opportunities Social workers on a day-to-day basis witness the impact of unmet needs on people from all walks of life in numerous institutional and community settings. As a profession rooted in practice, social work requires a clear philosophical framework rooted in the longstanding values and commitments of the profession (Reamer, 1993). Social work has pioneered issues of human need, and as Bremner pointed out decades ago, “Human need is a continuing fact, which each age discovers, or thinks it discovers, afresh” (Bremner, 1956, p. xiii). 21 As we have sought to demonstrate in this article, recent developments in theory and research on human need in philosophy and the social sciences justify bringing an end to social work’s ambivalence towards fully integrating human needs concepts into our theory and practice. A more explicit use of human needs-oriented concepts has potential as a central component of social work’s future philosophical base. A fuller incorporation of human needs concepts would help fulfill social work’s more established commitments to human rights and social justice. Human needs theory and research could also contribute to a unifying paradigm for social work practice. Doing so would help reduce the eclecticism which was seen as inhibiting the development of a new paradigm for social work (Tucker, 1996). Although the eco-systems perspective has been criticized on a number of grounds (Wakefield, 1996a, 1996b), the recognition that human needs are either realized or restricted at the intersection of the individual and the social environment would enrich the ecosystems perspective. If social work’s unique point of intervention is at that intersection, further development of needs-based theory and research in social work is essential. After all, social work theory should reflect the reality in which social workers work, a reality which is centered on human need. REFERENCES Abramovitz, M., & Blau, J. (1984). Social benefits as a right: A re-examination for the 1980s. Social Development Issues, 8(3), 50–61. Alkire, S. (2005). Needs and capabilities. In S. Reader (Ed.), The philosophy of need (pp. 229–251). Cambridge, U.K., New York: Cambridge University Press. Allen-Meares, P. (1987). Grounding social work practice in theory: Ecosystems. Social Casework, 68(11), 515–521. Applewhite, S. L. (1998). Culturally competent practice with elderly Latinos. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 30(1–2), 1–15. Bay, C. (1988). Human needs as human rights. In R. A. Coate & J. A. Rosati (Eds.), The power of human needs in world society (pp. 77–101). Boulder, CO: L. Rienner. Berg-Weger, M., Rubio, D. M., & Tebb, S. S. (2000). The caregiver well-being scale revisited. Health & social work, 25(4), 255–263. Bisno, H. (1952). The philosophy of social work. Washington: Public Affairs Press. 21 Blake, R. (1994). Diversity, common human needs and social welfare programs: An integrative teaching strategy. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 10(1–2), 129–135. Blau, J. (1992). A paralysis of social policy? Social Work, 37(6), 558–562. Boehm, W. (1956). The plan for the social work curriculum study. New York: Council on Social Work Education. Boehm, W. (1958). The nature of social work. Social Work, 3(2), 10–18. Booth, C. (1902). Life and labour of the people in London. London: Macmillan. Bradshaw, J. (1972). The concept of need. New Society, 30, 640–643. Braybrooke, D. (1968). Let needs diminish that preferences may flourish. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press. Braybrooke, D. (1987). Meeting needs. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Bremner, R. H. (1956). From the depths: The discovery of poverty in the united states. New York: New York University Press. Briar, K. H. (1985). Emergency calls to police: Implications for social work intervention. Social Service Review, 59(4), 593–603. Brock, G. (Ed.). (1998). Necessary goods: Our responsibility to meet others’ needs. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. Buber, M. (1937). I and thou. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. Chapin, R. K. (1995). Social policy development: The strengths perspective. Social Work, 40(4), 506–514. Cofer, C. N. (1986). Human nature and social policy. In L. Friedrich-Cofer (Ed.), Human nature and public policy: Scientific views of women, children, and families (pp. 39–96). New York: Praeger. Conway, E. M. (2005). Collaborative responses to the demands of emerging human needs: The role of faith and spirituality in education for social work. Journal of Religion & Spirituality in Social Work, 24(1–2), 65–77. Costanza, R., Fisher, B., Ali, S., Beer, C., Bond, L., & Boumans, R., et al. (2007). Quality of life: An approach integrating opportunities, human needs, and subjective well-being. Ecological Economics, 61(2–3), 267–276. 21 Cox, E. O., & Joseph, B. H. R. (1998). Social service delivery and empowerment: The administrator’s role. In L. M. Gutiérrez, R. J. Parsons, & E. O. Cox (Eds.), Empowerment in social work practice: A sourcebook (pp. 167–186). Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole. Council on Social Work Education (CSWE). (2004). Educational policy and accreditation standards. Washington, DC: Council on Social Work Education. Darling, R. B., Hager, M. A., Stockdale, J. M., & Heckert, D. A. (2002). Divergent views of clients and professionals: A comparison of responses to a needs assessment instrument. Journal of Social Service Research, 28(3), 41–63. Devine, E. T. (1909). Misery and its causes. New York: Macmillan. Dokecki, P. R. (1985). Critique of the liberal welfare state: Markets, scholars, and professionals. The Urban and Social Change Review, 18(2), 13–15. Dover, M. A. (1992). Notes from the Winter of Our Dreams. Crossroads: Contemporary Political Analysis & Left Dialogue, 27(December), 20-22. Dover, M. A. (1993). A theory of human need (book review). BCR Reports: Publication of the Bertha Capen Reynolds Society, 5(2), 8. Doyal, L. (1998). A theory of human need. In G. Brock (Ed.), Necessary goods: Our responsibility to meet others’ needs (pp. 157–172). Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. Doyal, L., & Gough, I. (1991). A theory of human needs. New York: Guilford. Fraser, I. (1998). Hegel and Marx: The concept of need. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. Fromm, E. (1955). The sane society. New York: Rinehart. Galper, J. H. (1975). The politics of social services. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Germain, C. B., & Gitterman, A. (1979). The life model of social work practice. In F. J. Turner (Ed.), Social work treatment: Interlocking theoretical approaches (2nd ed., pp. 361– 384). New York: Free Press. Germain, C. B., & Gitterman, A. (1980). The life model of social work practice. New York: Columbia University Press. Gil, D. G. (1976). The challenge of social equality: Essays on social policy, social development, and political practice. Cambridge, MA: Schenkman. Gil, D. G. (1978). Clinical practice and politics of human liberation. Catalyst (US), 1(2), 61– 69. 21 Gil, D. G. (1984). Institutional abuse: Dynamics and prevention. Catalyst, 4, 23–42. Gil, D. G. (1992). Unravelling social policy: Theory, analysis, and political action towards social equality (5th ed.). Rochester, VT: Schenkman Books. Gil, D. G. (1998). Confronting injustice and oppression: Concepts and strategies for social workers. New York: Columbia University Press. Gil, D. G. (2004). Perspectives on social justice. Reflections: Narratives of Professional Helping, 10, 32–39. Gough, I. (2000a). The needs of capital and the needs of people: Can the welfare state reconcile the two? In I. Gough (Ed.), Global capital, human needs, and social policies selected essays, 1994–99 (pp. 3–29). New York: Palgrave. Gough, I. (2000b). Why do levels of human welfare vary across nations? In I. Gough (Ed.), Global capital, human needs, and social policies: Selected essays, 1994–99 (pp. 105–130). New York: Palgrave. Gough, I. (2003). Lists and thresholds: Comparing the Doyal-Gough theory of human need with Nussbaum’s capabilities approach. Bath, England: Well-Being in Developing Countries ESRC Research Group, University of Bath. Gough, I. (2004). Human well-being and social structures: Relating the universal and the local. Global Social Policy, 4(3), 289–311. Gough, I., & McGregor, J. A. (2007). Wellbeing in developing countries: From theory to research (1st ed.). Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. Guadalupe, J. L., & Freeman, M. L. (1999). Common human needs in the context of diversity: Integrating schools of thought. Journal of Cultural Diversity, 6(3), 85–92. Gutiérrez, L. M., Parsons, R. J., & Cox, E. O. (1998). A model for empowerment practice. In L. M. Gutiérrez, R. J. Parsons, & E. O. Cox (Eds.), Empowerment in social work practice: A sourcebook (pp. 3–23). Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole. Hage-Yehia, A. S. (1983). Peace and freedom in a reformulation of basic human needs: Implications for welfare theory and practice. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania. Hamilton, G. (1951). Theory and practice of social case work (2nd ed.). New York: Columbia University Press. Hamilton, L. (2003). The political philosophy of needs. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. 21 Harper, F. D., Harper, J. A., & Stills, A. B. (2003). Counseling children in crisis based on Maslow’s hierarchy of basic needs. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 25(1), 11–25. Hearn, G. (1979). General systems theory and social work. In F. J. Turner (Ed.), Social work treatment: Interlocking theoretical approaches (2nd ed., pp. 333–359). New York: Free Press. Heller, A. (1976). The theory of need in Marx. New York: St. Martin’s Press. Herman, R. D. (1978). A social welfare approach to the value issue in social problems theory. Humanity and Society, 2(3), 163–177. Heywood, F. (2004). The health outcomes of housing adaptations. Disability & Society, 19(2), 129–143. Hughes, J. (2000). Ecology and historical materialism. New York: Cambridge University Press. Ife, J. (2001). Human rights and social work: Towards rights-based practice. New York: Cambridge University Press. Illich, I. (1978). Toward a history of needs (1st ed.). New York: Pantheon Books. Jones, J., & Pandey, R. (1977). Social development: Implications for social work education. Social Development Issues, 1(3), 40–54. Joseph, B. R. (1986a). The discovery of need, 1880–1914: A case study of the development of an idea in social welfare thought. New York: Columbia University School of Social Work. Joseph, B. R. (1986b). Taking organizing back to the people. Smith College Studies in Social Work (Bertha Capen Reynolds’ Centennial Issue), 56(2), 122–131. Kadushin, A. (1959). The knowledge base of social work. In A. J. Kahn (Ed.), Issues in American social work (pp. 39–79). New York: Columbia University Press. Kahn, A. J. (1959). The function of social work in the modern world. In A. J. Kahn (Ed.), Issues in American social work (pp. 354). New York: Columbia University Press. Koltko-Rivera, M. E. (2006). Rediscovering the later version of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs: Self-transcendence and opportunities for theory, research, and unification. Review of General Psychology, 10(4), 302–317. Lee, D. (1948). Are basic needs ultimate? Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 43, 361–395. 21 Lee, D. (1959). Freedom and culture. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Lewin, K. (1947). Frontiers in group dynamics: Concept, method and reality in social science: Social equilibria and social change. Human Relations, 1(1), 13–31. Lichtenberg, P. (1969). Psychoanalysis: Radical and conservative. New York: Springer. Little, M., Axford, N., & Morpeth, L. (2004). Research review: Risk and protection in the context of services for children in need. Child and Family Social Work, 9(1), 105–117. Marx, K. (1978). Critique of the Gotha program. In R. C. Tucker (Ed.), The Marx-Engels reader (2nd ed., 788 + xlii p.). New York: Norton. Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370–396. Maslow, A. H. (1969). The farther reaches of human nature. Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 1(1), 1–9. Maslow, A. H. (1970). Motivation and personality (2nd ed.). New York: Harper & Row. Maslow, A. H. (1971). The farther reaches of human nature. New York: Viking Press. McHale, J., & McHale, M. C. (1978). Basic human needs: A framework for action (report to the united nations environment programme). New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Books. McHale, J., & McHale, M. C. (1979). Meeting basic human needs. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 442, 13–27. McMunn, A., Bartley, M., & Kuh, D. (2006). Women’s health in mid-life: Life course social roles and agency as quality. Social science & medicine, 63(6), 1561–1572. Moon, B. E. (1991). Basic human needs. In The political economy of basic human needs (pp. 3–19). Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. Mullaly, B. (2001). Confronting the politics of despair: Toward the reconstruction of progressive social work in a global economy and postmodern age. Social Work Education: The International Journal, 20(3), 303–320. Mulroy, E. A., & Ewalt, P. L. (1996). Affordable housing: A basic need and a social issue. Social work, 41(3), 245–249. Murray, H. A. (1938). Explorations in personality; A clinical and experimental study of fifty men of college age. New York: Oxford university press. Nixon, R. A. (1970). The limitations on the advancement of human welfare under monopoly capitalism. Paper presented at the 78th Annual Meeting of American Psychological Association, Miami. 21 Noble, F., & Wagner, D. (2004). Running as a radical: The challenge of mainstream politics. Journal of Progressive Human Services, 15(1), 1–24. Noonan, J. (2002). Between egoism and altruism: Outlines for a materialist conception of the good. Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy, 5(4), 68–86. Noonan, J. (2004). Death, life; war, peace: The human basis of universal normative identification. Philosophy Today, 48(2), 168–178. Noonan, J. (2005). Modernization, rights, and democratic society: The limits of Habermas’s democratic theory. Res Publica: A Journal of Legal and Social Philosophy, 11(2), 101–123. Noonan, J. (2006). Democratic society and human needs. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University. Nussbaum, M. C. (2000). Women and human development: The capabilities approach. New York: Cambridge University Press. Olson, L. K. (1982). The Political Economy of Aging: The State, Private Power and Social Welfare. New York: Columbia University Press. Olson, J. J. (2007). Social work’s professional and social justice projects: Discourses in conflict. Journal of Progressive Human Services, 18(1), 45–69. Percy-Smith, J. (1996). Needs assessments in public policy. Philadelphia: Open University Press. Percy-Smith, J., & Sanderson, I. (1992). Understanding local needs. London: Institute for Public Policy Research. Posner, W. B. (1995). Common human needs: A story from the prehistory of government by special interest. Social service review, 69(2), 188–225. Rawls, J. (1971). A theory of justice. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press. Reader, S. (2007). Needs and moral necessity. New York: Routledge. Reader, S. (Ed.). (2005). The philosophy of need. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Reamer, F. G. (1993). The philosophical foundations of social work. New York: Columbia University Press. Reamer, F. G. (1998). The evolution of social work ethics. Social Work, 43(6), 488. Reichert, E. (2003). Social work and human rights: A foundation for policy and practice. New York: Columbia University Press. 21 Reid, W. J. (1978). The task-centered system. New York: Columbia University Press. Reynolds, B. C. (1934). Between client and community; a study of responsibility in social case work. New York: Oriole. Richmond, M. E. (1922). What is social case work? An introductory description. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. Robertson, A. (1998). Critical reflections on the politics of need: Implications for public health. Social Science and Medicine, 47(10), 1419–1430. Robinson, V. P. (1930). A changing psychology in social case work. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. Rowntree, B. S. (1902). Poverty: A study of town life (2nd ed.). London: Longmans, Green & Co. Saleebey, D. (2006). The strengths perspective in social work practice (4th ed.). Boston: Pearson/Allyn & Bacon. Sartorius, R. H., & Ruttan, V. W. (1989). The sources of the basic human needs mandate. Journal of Developing Areas, 23(3), 331–362. Schiele, J. H. (1997). The contour and meaning of Afrocentric social work. Journal of Black Studies, 27(6), 800–819. Sen, A. K. (1985). Commodities and capabilities. New York: Elsevier. Sen, A. K. (1999). Development as freedom (1st ed.). New York: Knopf. Soper, K. (1981). On human needs: Open and closed theories in a Marxist perspective. Atlantic Highlands, NJ: Humanities Press. Spicker, P. (2007). Concepts of need. In The idea of poverty (pp. 29–42). Bristol, UK: Policy. Springborg, P. (1981). The problem of human needs and the critique of civilisation. Boston: Allen & Unwin. Steiner, J. (1986). Need structure and self concept of battered women. Garden City, New York: Adelphi University. Stroup, H. (1953). The field of social work. Sociology and Social Research, 37(6), 395–398. Sumerlin, J. R., & Norman, R. L. (1992). Self-actualization and homeless men a knowngroups examination of Maslow hierarchy of needs. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 7(3), 469–481. 21 Swartz, S. (1995). Community and risk in social service work. Journal of Progressive Human Services, 6(1), 73–92. Taylor, A. J. W. (Ed.). (2006). Justice as a basic human need. New York: Nova. Tebb, S. (1995). An aid to empowerment: A caregiver well-being scale. Health and Social Work, 20(2), 87–92. Thursz, D., & Vigilante, J. L. (1975). Meeting human needs: An overview of nine countries. Beverly Hills: Sage. Timms, N. (1983). Social work values: An enquiry. Boston: Routledge & Kegan Paul. Timms, N., & Timms, R. (1977). Some neglected key concepts. In N. Timms & R. Timms, Perspectives in social work (pp. 133–151). Boston: K. Paul Titmuss, R. M. (1968). Commitment to welfare. London: Allen & Unwin. Towle, C. (1965[1945]). Common human needs (Rev. ed.). Silver Spring, MD: National Association of Social Workers. Tucker, D. J. (1996). Eclecticism is not a free good: Barriers to knowledge development in social work. Social Service Review, 70(3), 400–434. United Nations. (1954). Report on international definition and measures of standards and levels of living. New York: United Nations. Vasey, W. (1958). Government and social welfare; roles of federal, state, and local governments in administering welfare services. New York: Holt. Vigilante, F. W., & Mailick, M. D. (1988). Needs-resource evaluation in the assessment process. Social Work, 33(2), 101–104. Wakefield, J. C. (1988). Psychotherapy, distributive justice, and social work—part 2. Social Service Review, 62(3), 353–382. Wakefield, J. C. (1996a). Does social work need the eco-systems perspective? Part 1. Is the perspective clinically useful. Social Service Review, 70(1), 1-32. Wakefield, J. C. (1996b). Does social work need the eco-systems perspective? Part 2. Does the perspective save social work from incoherence. Social Service Review, 70(2), 183-213. Warshawsky, R. (1985). Social justice and the welfare state. The Urban and Social Change Review, 18(1), 20–24. Webb, S., & Webb, B. P. (1927). English local government: English poor law history. London: Longmans, Green & Co. 21 Wilensky, H. L., & Lebeaux, C. N. (1958). Industrial society and social welfare; the impact of industrialization on the supply and organization of social welfare services in the united states. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. Witkin, S. L. (1998). Human rights and social work. Social Work, 43(3), 197–201. Wolins, M. (1967). The societal function of social welfare. In N. Gilbert & H. Specht (Eds.), The emergence of social welfare and social work (pp. 106-133). NewYork: Peacock. Wringe, B. (2005). Needs, rights and collective obligation. In S. Reader (Ed.), The philosophy of need (pp. 287–208). New York: Cambridge University Press. Wronka, J. (1992). Human rights and social policy in the 21st century. NY: University Press of America. Wronka, J. (2008).. Human rights and social justice: Action and service for the helping and health professions. Lanham, MD: Sage. Zalenski, R. J., & Raspa, R. (2006). Maslow’s hierarchy of needs: A framework for achieving human potential in hospice. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 9(5), 1120–1127. 21