New breed of organized crime emerges

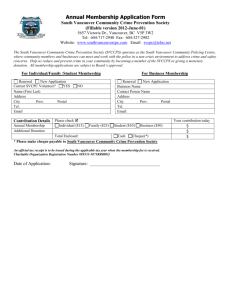

advertisement