Andrew Jackson

advertisement

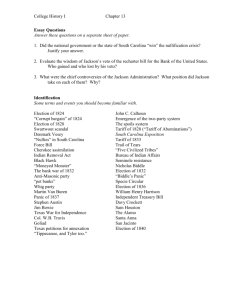

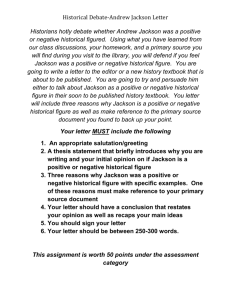

The Big Picture: Who, What, When, Where & (Especially) Why Andrew Jackson: Hero and Villain, Democrat and Tyrant Historians just can't seem to agree about Andrew Jackson. Some see him as a hero; others believe he was a villain. Some portray him as the common man's warrior, a president who attacked a political system that ignored the people's will. Others say that he was a political tyrant, an executive bully who disrespected the processes and institutions essential to republican government. Some celebrate his liberal defense of individual rights; others condemn his racist removal of 90,000 Indians. Some view him as a great nationalist who saved the Union by denouncing nullification. Others claim that he weakened the nation by supporting Georgia in its defiance of the Supreme Court. The problem is that all of these conclusions are true. Jackson ran for president in 1828 determined to restore the will of the people to politics. He believed that Washington power brokers had ignored the people's wishes in 1824 when they deprived him of the presidency despite winning a plurality of the popular vote; true democracy, he felt, would not be realized until America's political processes were significantly reformed. As a candidate, Jackson built a political organization that reached out directly to the public, and as president he attacked the institutions that he believed deepened divisions between the rich and the poor. But Jackson also showed little patience for political processes and institutions that interfered with his "democratic" agenda. He encroached further upon the legislative process than his predecessors, advancing a theory of presidential power that many believed threatened the separation of powers essential to republican government. Jackson showed greater respect for individual political and economic rights than any previous president. He sought to increase the number of offices directly elected by the people, and he sought to restore an economic system that protected the rights of small producers rather than corporations and the wealthy. But when Native Americans turned to the federal government to support their territorial claims, even winning a Supreme Court ruling that affirmed those claims, Jackson turned a deaf ear. He ignored three decades of government precedent, and a clear Court ruling, while implementing a removal policy that displaced over 90,000 people. Jackson took on the state of South Carolina, denounced its nullification theories, and threatened to bring in the United States army to enforce federal law. In doing so, he broke with his vice-president and alienated a portion of his southern political base. He accepted an alliance with politicians he did not respect and who did not respect him. And he outlined an original theory of the Union that would serve Abraham Lincoln when he faced a similar secessionist crisis thirty years later. But Jackson also weakened national authority by siding with the states' rights arguments of Georgia in its battle over federal Indian policy. He undercut the authority of the Supreme Court, approving of Georgia's efforts to circumvent the will of the Court in its assertion of federal law. In short, Jackson was a confusing figure. He was a democrat and a tyrant, a nationalist and a supporter of states' rights. He defended the political and economic rights of common people but ignored the territorial rights of Native Americans. The Age of Jackson 1828-1836: The Good, the Bad, the Evil 1. 2. 3. 4. How could democracy simultaneously expand and decrease? What role did Jackson have in both? How did the masses of Americans participate in politics? How did American Indians react to the growth of the U.S. under the Jackson administration? What characterizes “Jacksonian Democracy”? DEMOCRATIC REVOLUTION Between 1820 and 1840, a DEMOCRATIC REVOLUTION transformed American politics with INCREASED VOTER PARTICIPATION and OFFICE-HOLDING. Two important features of this democratization were: The emergence of the second-party system of Democrats and Whigs The importance of a candidate’s popularity with the "common man" in determining the outcome of elections. ELECTION OF 1828 Popular Politics The Election of 1828 was the first presidential contest where popular votes determined the victor. The election also inaugurated modern-day electioneering, as many state-level candidates gave speeches, held barbecues attract voters, and included “stump speeches” and partisan newspapers. Both sides used character assassination, or rumors and investigations into the “real lives” of the other candidate Showed a new approval of political parties, solidified party loyalties By 1828, party labels appeared, with Andrew Jackson's followers assuming the name of Democratic Republicans, and those in the Adams-Henry Clay coalition calling their party the National Republicans. By 1836, Jacksonians simply referred to their organization as the Democratic Party, and the National Republicans had evolved into the Whig Party. JACKSON’S POPULARITY Image: Military Hero Frontiersman Champion of the People Reality: Wealthy Lawyer/Judge Cultured Gentleman JEFERSONIAN V. JACKSONIAN DEMOCRACY Jackson's election was a victory for the common man (the small farmer and city worker) over the aristocracy of money, factory, and land. The common people viewed Jackson as one of their own. Since Jackson opposed special privilege and campaigned as the champion of the people, his election is often referred to as the Revolution of 1828. By 1828, most states had removed property and religious qualifications for office holding and voting, increased the number of elected state and local offices, and gave the people a greater check upon elected officials by shortening their terms of office. Beginning with the election of 1832, instead of being named by a caucus of a few party leaders, the candidate of each party was named by a number of active party members at a nominating convention. Presidential electors (Electoral College) of all but one of the states were chosen directly by the voters instead of by state legislatures. JEFFERSON JACKSON Believed that capable, welleducated leaders should govern in the people's interest. Represented an agricultural society. Limited democracy to its political aspects Believed that people themselves should manage their governmental affairs. Represented a rising industrial society as well as an agricultural one Expanded democracy from its political aspects to include social economic aspects Jackson held that the President, the only nationally chosen official, was the servant of the people, elected to further their interests and protect their rights. To achieve these purposes, Jackson used his powers vigorously: POLITICAL ASPECTS OF JACKSONIAN ERA He employed the veto more than all the preceding Presidents together. He prepared to use force when South Carolina challenged the authority of the federal government He refused to enforce John Marshall's decision prohibiting Georgia from seizing Cherokee Indian lands (Indian Removal Act of 1830) He believed that limited terms of office was democratic because it prevented a permanent class of officeholders from becoming an aristocracy Jackson's enemies referred to him as “King Veto” and “King Andrew I”. They called themselves Whigs, as had the 18th century opponents, of monarchical power in England. To the common man, however, Jackson remained both a valiant hero and a democratic servant. Jackson was the first president to use the spoils system widely, giving federal offices to members of his party to gain support. A Jacksonian supporter coined the phrase, "To the victor belong the spoils." POLITICS OF OPPORTUNITY Western Expansion, Indian Removal, & the Trail of Tears The Tariff of Abominations and Nullification Carrot & Stick: Lower Tariff + Force Bill The Bank War & In his two terms as president, Andrew Jackson worked to enact his vision of a politics of opportunity for all white males. The primary issues of his tenure were westward expansion, Indian removal, nullification, and "war" with the second Bank of the United States. When Jackson became president, a substantial number of Native Americans remained east of the Mississippi River, and he wanted them removed. The government's attempt in 1832 to relocate reluctant western Illinois tribes erupted into war and led to a major defeat for the Indians. The government hoped to remove the southern tribes of Creek, Chickasaw, Choctaw, and Cherokee to the West to open their lands for white settlement and cotton cultivation. Cherokee tried to stop encroachments through cases in the Supreme Court. Jackson repudiated the Court's decisions in their favor, and in 1835, the government was able to make a treaty with a minority faction of the tribe, ceding to Georgia the Cherokee's land in return for $5 million and land in present-day Oklahoma. When the majority of the Cherokee who did not recognize the treaty refused to move, Jackson sent federal troops in the winter of 1838, to force them to move on a twelvehundred-mile journey west. Along this "trail of tears," nearly a quarter of the Cherokee perished. The federal government passed tariffs to protect American manufactures and raise revenue in 1816 and 1824, over the protest of southern congressmen who feared the effects the tariffs would have on the southern export economy. In 1828, a tariff passed for the benefit of the North brought controversy when Southerners opposed the measure, labeling it the "tariff of abominations." South Carolinians, led by John Calhoun, decided to nullify, or make invalid, the despised federal tariffs they believed were responsible for their state's economic stagnation. In response, Jackson sent warships to Charleston and pushed through Congress a Force Bill granting him the authority to use military force if necessary to uphold the tariff laws. As tensions escalated, Henry Clay fashioned a compromise (Compromise Tariff of 1833) that got the South Carolinians the lower tariff they wanted. The major political issue of Jackson's presidency was not the tariff but his war against the Bank of the United States. the Panic of 1837 DECLINE OF DEMOCRATIC PARTY Van Buren Election of 1840: Victory for Whigs Democrats and Whigs Though the bank had had a stabilizing effect on the economy, Jackson considered it a stronghold of elitism, concentrating great power in the hands of a privileged few. Jackson vetoed a plan for the Bank’s recharter in 1832, creating popular antibank sentiment. He ordered all federal deposits withdrawn and redeposited in selected state banks. A fury of speculation ensued, especially in land. In an attempt to control the economy, Jackson issued the Specie Circular, which, along with other factors, crated the Panic of 1837, and another five years of economic hard times followed. Martin Van Buren's political acuteness earned him the nickname "the Little Magician." Elected in 1836, the new president spent the bulk of his four years attempting to deal with the Panic of 1837. As the election of 1840 drew near, the Whigs anticipated victory. They settled on candidate William Henry Harrison to oppose Van Buren. The 1840 campaign was one of the most dramatic, participatory, and exciting in American history. Harrison and the Whigs won a resounding victory in both the popular vote and electoral college. Democratic control over American politics was temporarily over. Democrats put together a coalition of farmers, laborers, commercial men, and slave owners who embraced personal liberty, free competition, and opportunity open to all white men. The Whigs and third parties, were moralistic and favored state (government)sponsored entrepreneurship. National politics were heated and divisive in the 1830s, and voter turnout was high because politics was where different choices about economic development and social change were made. Controversy over issues like slavery, free labor, and women's rights, led to the growth of third parties in the 1840s and eventually undermined the Democratic-Whig party system. DISCUSSION QUESTIONS The Jacksonian presidency was characterized by a “politics of opportunity” that served some groups at the expense of others. Discuss how westward expansion, Indian removal, nullification, and the "war" with the second Bank of the United States fit this pattern. In each case, who benefited and who lost? If the Democrats were the party of personal liberty, free competition, and opportunity, why did they decline after 1840? What campaign strategies were used in the election of 1828? To what extent are the same campaign strategies used today? Give examples of how recent elections have mirrored the pattern established in 1828 of candidates projecting one image but in reality representing something quite different. Determine whether the political, economic, and cultural developments of the Jacksonian Era actually contributed to the well-being of the common people or simply helped candidates to win elections.