Newspaper Template Volume 1, Issue 1 April 2011 Sidebar

advertisement

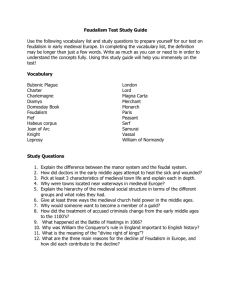

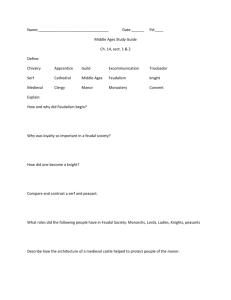

NEWSPAPER TEMPLATE Volume 1, Issue 1 April 2011 Research & Analysis Project Spring 2011 Instructions for Using This Template Type your sub-heading here Dr. Sarah Vonhof Columnist Instructor, ESF Press This is a template from Microsoft Word for a newsletter. That’s a bit different than a newspaper, but I thought it would help to have columns and headings set up and a layout from which to begin. Don’t forget to include citations as endnotes! (See the sidebar article). If we cannot discern your quotation (whether it is primary or secondary) you will not receive credit. Remember that the sample online was from a prior year and had different criteria. Review the grading rubric and the notes on secondary citations on the course website. Also read through the syllabus description before you finalize your project. The teaching team is happy to review drafts and provide comments and suggestions. Your By-line Your Company Name Using Styles in This Template To change the Style of any paragraph, select the text by positioning your cursor anywhere in the paragraph. Select a Style from the drop-down Style list at the top-left of your screen. Press Enter to accept your choice. The styles available in this template allow you to change the look of your headlines and other text. The remainder of what follows is from Microsoft—a set of instructions for working with this template. continued on page 2 SIDEBAR / ADVERTISEMENT? See Page 4 to learn how to edit or replace this picture. The following is a list of some styles and their uses: Body Text - Use this style for the regular text of an article. Byline - Use this style for the name of the author of an article. Byline Company - Use this style to type the author’s company. continued on page 3 Newsletter 1 continued from page 1 This document was created using linked text boxes, which allow articles to flow continuously across pages. For example, this article continues on page two, while the one to the right continues on page three. When you add lines of words to a text box, the words in the following text box flows forward. When you delete lines of words from a text box, the words in the next text box move backward. You can link several text boxes in an article, and you can have multiple articles in a document. The links do not have to occur in a forward direction. Inserting Linked Text Boxes To insert linked text boxes in a document, click Text Box on the Insert menu. Click and drag in your document where you want to insert the first text box, and insert additional text boxes where you want the text to flow. To select the first text box, move the pointer over the border of the text box until the pointer becomes a four-headed arrow and then click the border. Click the right mouse button and then click Create Text Box Link. Click in the text box where you want the text to flow. (When you move the upright pitcher over a text box that can receive the link, the pitcher turns into a pouring pitcher.) Repeat these steps to create links to additional text boxes. In the first text box, type text that you want. As the text box fills, the text will flow into the other text boxes that you’ve linked. Formatting Text Boxes You can change the look of linked text boxes by using color, shading, borders, and other formatting. Select the text box you want to format and then double click its border to open the Format Text Box dialog box. If you want to change the color or borders on a text box, choose the Colors and Lines tab. To change the size, scale, or rotation, click the Size tab. To change the position of the text box on the page, click the Position Tab. If you have other text surrounding the text box, and want to change the way the text wraps around it, click the Wrapping tab. If you want to format all the text boxes in an article, you must format them individually - the formatting on one text box will not apply to the others in the sequence. Using Linked Text for Parallel Articles You can use linked text boxes to flow text in parallel “columns” from page to page. This method gives different results than using the Column command on the Format menu, which causes text in column 1 to flow or “snake” to column 2 on the same page. By using linked text boxes, you can instead have text from column 1 flow to column 1 on the next page. The text beside it in column 2 can flow to column 2 on the next page, parallel to column 1. This technique is useful if you need to group two similar articles, for instance, an article translated in English on the left and the same article translated in French on the right. To flow text in parallel, display paragraph marks in your document. Click at the top of the page where you want the side-by-side columns to start, and press Enter twice. Click in the first paragraph mark on the page. On the Insert menu, click Text Box and drag on the page where you want the first column. Click Text Box again and then click and drag where you want the second column. Click in the last paragraph mark on the page, and press Ctrl + Enter to create a page break. Repeat the process for each page that will contain side-byside columns in your document and then return to the first text box you created. Click the text box on the left once to select it. Click your right mouse button and then click Create Text Box Link. The pointer becomes a pitcher. Click the text box on the left side of the second page to create a link. Create links for all text boxes within the same article on the left side of the document. Repeat the process for every text box in the right chain or article. Pressing Enter twice at the top of each page will create an extra empty paragraph. This blank paragraph is useful if you want to insert text or graphics outside of the text boxes. You can delete the extra blank paragraph if you don't need it. Copying linked text boxes You can copy an article or a chain of text boxes that are linked together, to another document or to another location in the same document. To copy linked text boxes and the text they contain, you must copy all the linked text boxes in an article. Select the first text box in an article. Hold down Shift, and click each additional text boxes you want to copy. On the Edit menu, click Copy. Click where you want to copy the text boxes and then click Paste. To copy some of the text from an article, select the text you want to copy from the article and then copy it. Do not select the text box. You can paste text you’ve copied directly into your document, into another location within the same article, Newsletter 2 or into another article. Notes on Linked Text Boxes continued from page 1 SIDEBAR ARTICLES This sidebar article was created by inserting a text box and then changing the color and line formatting. You can use a sidebar article for any information you want to keep separate from other articles or information that highlights an article next to it. These could include a smaller self-contained story, an advertisement, or whatever – be creative. (Italicized suggestion added by Dr. V) INSTRUCTIONS FOR ENDNOTES From Dr. V…. a must read :-) Endnotes are formatted differently than footnotes, but they contain all of the citation information. They should be numbered consecutively, and sequentially. (That means you don’t use number 1 more than once. ) If you are not sure about your citation, please check with Dr. Vonhof or (worst case) add the text “primary source” at the end of your endnote. At least we will evaluate the quote as such, rather than not knowing it was one of your primary sources. With endnotes, the first time you cite a source you need the full-blown citation. Upon subsequent references, you can simply type the last name of the author, the titles, and the page number. I’ve copied part of my dissertation notes to the last page to illustrate (Chicago style). Of course, these are just the endnotes—the superscript notes (the numbers) should be in the text of your article. The version of Word that I now have requires you to compose your bibliography through something called “The Source Manager.” This can be accessed from the Document Elements tab—then References / Manage. From there you can add sources and then citations. You may have to compose secondary citations manually. Consult the help menu if you have troubles. SIDEBAR HEAD - Use this style to type a second-level heading in a sidebar article. SIDEBAR SUBHEAD - Use this style to type a third-level heading in a sidebar article. Sidebar Text - Use this style to type the text in a sidebar article. SIDEBAR TITLE - Use this style to type first-level headings in a sidebar article. Footer - Use this style to type the repeating text at the very bottom of each page. Heading1 - Use this style to create headlines for each article. Heading2 - Use this style to create section headings in an article. Jump To and Jump From - Use these styles to indicate that an article continues on another page. Mailing Address - Use this style in a mailing label to type the destination address. POSTAGE - Use this style in a mailing label to type postage information. Return Address - Use this style in a mailing label to type your address. Picture Caption - Use this style to type a description of a picture or illustration. Subtitle - Use this style to type sub-headings in an article. Use PullQuote to excerpt text from the main text of a story to draw a reader’s attention to the page. See page 4 for an example. And remember… you still have to compose a complete bibliography of all the sources you researched—not just those you cited or quoted. Newsletter 3 MORE WAYS TO CUSTOMIZE THIS TEMPLATE Inserting and Editing Pictures Type your sub-heading here FOOTERS To change the text at the very bottom of each page of your newsletter, click Headers and Footers on the View menu. Use the Header and Footer toolbar to open the footer, and replace the sample text with your own text. INSERT SYMBOL It is a good idea to place a small symbol at the end of each article to let the reader know that the article is finished and will not continue onto another page. Position your cursor at the end of the article, click Symbol on the Insert menu, choose the symbol you want, and then click Insert. CONTINUED TEXT To let the reader know that an article will continue on another page, insert a small text box under the text box, choose the Continued To style, and then type the words “Continued on Page”. QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS Q: I would like to change some of the text box shading to improve the print quality. Can that be done? A: Yes. To change the shading or color of a text box, select it and double click its borders to open the Format Text Box dialog box. Click the Colors and Lines tab and then choose the new color from the Color dropdown list in the Fill section. Q: What’s the best way to print this newsletter? A: Print page 2 on the back of page 1. Fold in half and mail with or You can replace the pictures in this template with your company’s art. Select the picture you want to replace, point to Picture in the Insert menu, and click From File. Choose a new picture and then click Insert. Select the Link to File box if you don’t want to embed the art in the newsletter. This is a good idea if you need to minimize your file size; embedding a picture adds significantly to the size of the file. To edit a picture, click on it to activate the Picture toolbar. You can use this toolbar to adjust brightness and contrast, Choose a new picture, and click the Link to File box if you don’t want to save the art with the newsletter. change line properties and crop the image. For more detailed editing, double-click on the graphic to activate the drawing layer where you can group or ungroup, re-color, or delete picture objects. without an envelope. For best results, use a medium to heavyweight paper. If you’re mailing without an envelope, seal with a label. change the text in the footer, select it and type your new text. To change the border, click Borders and Shading on the Format menu. Q: I would like to use my own clip art. How do I change the art without changing the design? Q: Can I save a customized newsletter as a template for future editions? A: To change a picture, click on the picture, then point to Picture on the Insert menu and click From File. Choose a new picture, and click Insert. A: Yes. Type your own information over the sample text and then click Save As on the File menu. Choose Document Template from the Save as type drop down list (the extension should change from .doc to .dot). Save the file under a new name. Next time you want to create a newsletter, click New on the File menu, then choose your template. Q: How do I change the text and borders that appear at the bottom of every page? A: Click Headers and Footers on the View menu. Use the Header and Footer toolbar to navigate among headers and footers, insert date or time, or format the page numbers. To Newsletter 4 ENDNOTES 1 Robert C. Palmer, AThe Origins of Property in England,@ Law and History Review 3 (1985): 7. 2 R. Allen Brown, Origins of English Feudalism (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1973) 28. Interestingly enough, the word feudal did not appear in the English language until 1614; and although Adam Smith used feudal system in 1776, feudalism was not used until 1839. Ibid., 21; The Barnhart Concise Dictionary of Etymology. 3 David Herlihy, Introduction to Part Two: Feudal Institutions, In The History of Feudalism, ed. David Herlihy (New York: Harper & Row, 1970) 74. Palmer, AThe Origins of Property in England,@ 5. 4 5 Marc Bloch, Feudal Society, Vol. 1, The Growth of Ties and Dependence, trans. L.A. Manyon (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1961) 115. 6 Marc Bloch, Feudal Society, Vol. 2, Social Classes and Political Organization, trans. L.A. Manyon (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1961) 445. Allodial is the term for unconditional tenure. In Anglo-Saxon England, bocland or book-land was not subject to services or rent. In modern usage, allodial denotes an estate in fee simple absolute. 7 John Hudson, Land, Law, and Lordship in Anglo-Norman England (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1994) 9. 8 Kenneth Pennington, The Prince and the Law 1200-1600 (Berkeley; University of California Press, 1993) 4. 9 Sir Frederick Pollock and F. W. Maitland, The History of English Law before the Time of Edward I, vol i, second ed. (Cambridge: N.p., 1968) xlvii; cited in Hudson, Land, Law, and Lordship, 9. 10 Sir Frederick Pollock, The Land Laws, second ed. (London: Macmillan and Co., 1887) 53. 11 F. L. Ganshof, Feudalism, trans. Philip Grierson, Third English ed. (New York: Harper & Row, 1964) xv. 12 Bloch, Feudal Society, 2: 446. 13 Brown, Origins of English Feudalism, 32. 14 Ibid., 83, 21. 15 Eric Kerridge, Agrarian Problems in the Sixteenth Century and After (London: George Allen and Unwin, 1969) 61. 16 J. C. Holt, Magna Carta and Medieval Government (London: Hambleton Press, 1985) 11. 17 Kerridge, Agrarian Problems in the Sixteenth Century and After, 61. 18 Kerridge, Agrarian Problems in the Sixteenth Century and After, 60. 19 Hudson, Land, Law, and Lordship, 209. 20 Harris, Origin of the Land Tenure System, 25. 21 Trevor Rowley, AMedieval Field Systems,@ In The English Medieval Landscape, Leonard Cantor, ed. (London: Croom Helm, 1982) 29-30. Newspaper Template 5 22 Leonard Cantor, AForests, Chases, Parks, and Warrens,@ In The English Medieval Landscape, Leonard Cantor, ed. (London: Croom Helm, 1982) 56, 82. 23 Pollock, The Land Laws, 41. 24 Holt, Magna Carta and Medieval Government, 22. 25 V. H. Galbraith, The Making of Domesday Book (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1961) 160; cited in Brown, Origins of English Feudalism, 87. 26 Brown, Origins of English Feudalism, 53, 87. 27 D. C. Douglas, William the Conqueror (N.c.: Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1964) 372; cited in Cyril E. Hart, Royal Forest (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1966) 7. 28 Oliver Rackam, Ancient Woodland (London: Edward Arnold, 1980) 175. 29 Hart, Royal Forest, xix. 30 Cantor, AForests, Chases, Parks, and Warrens,@ 62. 31 Ibid., 57-8. 32 Charles R. Young, The Royal Forests of Medieval England (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1979) 167-8. 33 John Gillingham, The Normans, In The Lives of the Kings & Queens of England, Antonia Fraser, ed. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995) 41. 34 Ibid., 42. 35 Palmer, AThe Origins of Property in England,@ 9. 36 Hudson, Land, Law, and Lordship, 150. 37 Palmer, AThe Origins of Property in England,@ 3. 38 AIf any free tenant dies, let his heirs remain in such seisin of his fee as their father had on the day on which he was alive and dead.@ Assize of Northampton, c. 4, Select Charters and Other Illustrations of English Constitutional History from the Earliest Times to the Reign of Edward I, ninth ed. , ed. W. Stubbs (Oxford.: Oxford University Press, 1913) 179; cited in Hudson, Land, Law, and Lordship, 69. 39 Palmer, AThe Origins of Property in England,@ 7. Palmer states that Athere were only two elemental legal ideas in twelfth century England: wrongs and obligations.@ Ibid., 8. 40 Hudson, Land, Law, and Lordship, 270. 41 Young, The Royal Forests of Medieval England, 18. 42 P. R. Hyams, AWarranty and Good Lordship in Twelfth Century England,@ Law and History Review 5 (1987): 478; cited in Hudson, Land, Law, and Lordship, 258. 43 Cantor, AForests, Chases, Parks, and Warrens,@ 61. 44 Young, The Royal Forests of Medieval England, 28. 45 Hart, Royal Forest, 13. Newspaper Template 6 46 David C. Douglas, and George W. Greenway, eds. English Historical Documents 1042-1189, vol. 2 (London: n.p., 1953) 418-20; cited in Young, The Royal Forests of Medieval England, 28. 47 Ibid. 48 Holt, Magna Carta and Medieval Government, 20. 49 Young, The Royal Forests of Medieval England, 171. 50 Ibid., 135. 51 Holt, Magna Carta and Medieval Government, 173. 52 Ibid., 128. 53 Ibid., 97. 54 Ibid., 166. 55 Ibid., 173. 56 Young, The Royal Forests of Medieval England, 164-65. 57 Ibid., 68. 58 Hainsworth, Stewards, Lords, and People, 6. 59 Leonard Cantor, AIntroduction: The English Medieval Landscape,@ In The English Medieval Landscape, Leonard Cantor, ed. (London: Croom Helm, 1982) 19. 60 Marion Clawson, Man and Land in the United States (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1964) 11. The tripartite class division of landlord, tenant farmer, and laborer is often taken as an indicator of agrarian capitalism. However, this period is not labeled as such because there is not a capitalist production process: farmers are subsistence farmers and their decisions about what to produce are not determined by the market. Overton, Agricultural Revolution in England, 203-4. 61 With the increase in population, the only way to increase food production was to decrease the area of royal forest, since all lands suitable for agriculture had already been used. 62 Young, The Royal Forests of Medieval England, 147. 63 Cantor, AForests, Chases, Parks, and Warrens,@ 66. 64 Ibid., 69, 66. 65 Young, The Royal Forests of Medieval England, 154. 66 William B. Greeley, Forest Policy ( New York: McGraw Hill, 1953) 108. 67 Overton, Agricultural Revolution in England, 151. The termination of customary (copyhold) tenures and the establishment of leaseholds were two other changes associated with enclosure. These are discussed in the context of the emergence of property in land in the sixteenth century. 68 Ibid., 4. 69 Matthew Johnson, An Archeology of Capitalism (Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 1996) 48. Newspaper Template 7 70 M. W. Beresford and J. G. Hurst, eds., Deserted Medieval Villages (Guildford: Lutterworth Press, 1971) 12-14; cited in Cantor, AIntroduction: The English Medieval Landscape,@ 22. 71 Robert C. Allen, Enclosure and the Yeoman (Oxford: Clarendon Press,1992) 14; cited in Robert C. Ellickson, AProperty in Land,@ Yale Law Journal 120 (1993): 1392. 72 A. R. H. Baker, AChanges in the Later Middle Ages,@ In A New Historical Geography of England before 1600, H. C. Darby, ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1976) 195; cited in Cantor, AIntroduction: The English Medieval Landscape,@ 21. 73 Joan Thirsk, AEnclosing and Engrossing,@ In Agricultural change: policy and practice 1500-1750, Vol 3. of Chapters from The Agrarian History of England and Wales, Joan Thirsk, ed., (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990) 61. 74 Ibid., 68. 75 Ibid., 76 John E. Martin, Feudalism to Capitalism: Peasant and Landlord in English Agrarian Development, (Atlantic Highlands: Humanities Press, 1983) 102. 77 Johnson, An Archeology of Capitalism, 54. 78 Thirsk, AEnclosing and Engrossing,@ 54. 79 Christopher Hill, The English Bible and the Seventeenth Century Revolution (London: Allen Lane, 1993) 133; cited in Johnson, An Archeology of Capitalism, 58. 80 Overton, Agricultural Revolution in England, 148. 81 Joan Thirsk, AAgricultural Policy: Public Debate and Legislation, 1640-1750,@ In Agricultural change: policy and practice 1500-1750, Vol 3. of Chapters from The Agrarian History of England and Wales, Joan Thirsk, ed., (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990) 145. 82 Johnson, An Archeology of Capitalism, 76. 83 Overton, Agricultural Revolution in England, 165. 84 Johnson, An Archeology of Capitalism, 206. 85 Scott, In Pursuit of Happiness, 9. 86 The death of King Richard III in 1485 is traditionally taken as the division between the medieval and modern era. 87 Kerridge, Agrarian Problems in the Sixteenth Century and After, 23. 88 Pollock, The Land Laws, 97, 104. The statutes are the Statute of Uses and the Statute of Enrollments. 89 Seipp,@The Concept of Property in the Early Common Law,@ 66. 90 Ibid., 84; footnote omitted. 91 Ibid., 84. 92 Ibid., 87. 93 Max Weber, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, trans. Talcott Parsons (1930; reprint, London: Routlege, 1992) 80. Newspaper Template 8 94 Schlatter, Private Property, 80. 95 Ibid., 80. 96 Ibid., 85. 97 Pocock, The Machiavellian Moment, 348. 98 Holt, Magna Carta and Medieval Government, 17. 99 Pocock, The Machiavellian Moment, 348. See also Pockock, The Ancient Constitution and the Feudal Law, Chs. II and III. 100 J. P. Sommerville, Politics and Ideology in England, 1603-1640 (London: Longman, 1986) 145. 101 Ibid., 148. 102 Appleby, Liberalism and Republicanism in the Historical Imagination, 51. 103 Brown, Origins of English Feudalism, 91. 104 Holt, Magna Carta and Medieval Government, 19. 105 Military tenures and their incidents were abolished by Charles II in 1660 with the restoration of the monarchy. Taking the premise that feudalism originated with the knight and his fief, it follows that it would end officially with the abolition of military tenures. 106 Wood, The Politics of Locke=s Philosophy, 15-20. 107 Clawson, Man and Land, 10. 108 Alfred N. Chandler, Land Title Origins: A Tale of Force and Fraud (New York: Robert Schalkenbach Foundation, 1945) 47. 109 Scott, In Pursuit of Happiness, 10. Newspaper Template 9