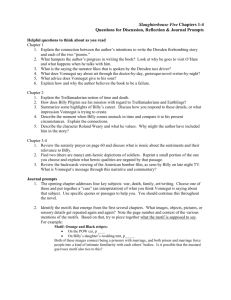

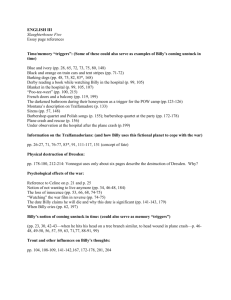

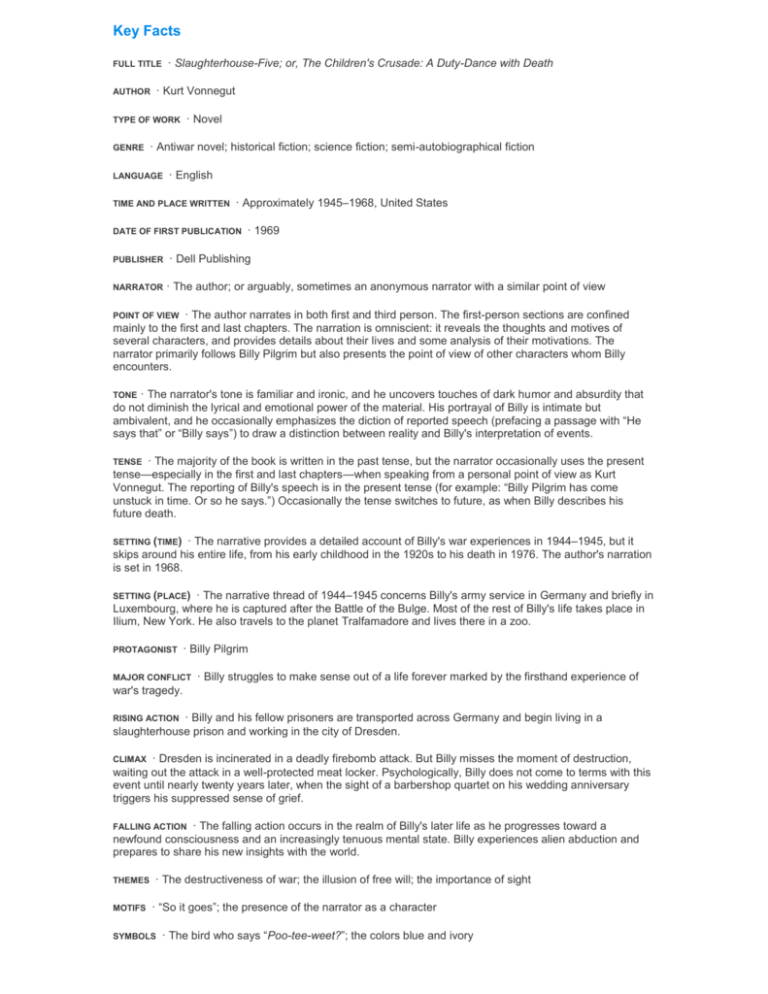

Slaughterhouse Five Sparknotes.doc

advertisement