From “Providing Housing” - Albany Housing Authority

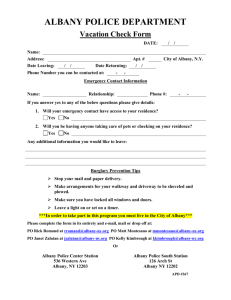

advertisement