Beowulf Essay.doc - The Risberg Family

advertisement

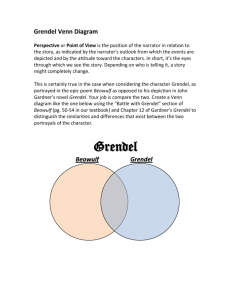

Risberg 1 Lauren Risberg Ms. Stegmiller British Literature E 21 October 2008 The War Against Paganism The story of Beowulf occurs in a pagan society that adheres to a code favoring authoritarianism, vengeance, and material wealth – all of which are values that led the Anglo-Saxons into a chaotic lifestyle full of wars with neighboring tribes and cutthroat vendettas against their brothers. In this Anglo-Saxon epic poem, their wars with neighbors are replaced with wars against demons, but the same drive for blood and wealth remains in their monstrous fictitious enemies and continues to wreak death and destruction. The evil monsters in Beowulf, translated by Seamus Heaney, are motivated by pagan principles that are also taboos of Christianity, and their portrayal in the poem eventually paves the way towards stabilization of the chaotic pagan culture through Christianity. Jealousy is one such Christian taboo that leaks into Heorot and Beowulf must meet and battle with in the form of Grendel. First, in the Christian Bible, jealousy appears in stories that demonstrate the horrible possibilities that could arise if one indulges in envy. In the story of Cain and Abel, for example, jealousy is the iniquitous human emotion that ultimately leads to fratricide and exile. The Bible clearly states that jealousy is a treacherous human fault that can be dangerous: “Jealousy is cruel as the grave. Its flashes are flashes of fire, a most vehement flame”(Song of Songs 8:6). Christians are encouraged to let go of their envy, but the Risberg 2 inhuman fiend, Grendel, initially appears in Beowulf as a monster who is absolutely consumed by greed and resentment: A powerful demon, a prowler through the dark, nursed a hard grievance. It harrowed him to hear the din of the loud banquet every day in the hall, the harp being struck and the clear song of a skilled poet telling with mastery of a man’s beginnings. (lines 86–91) As an outsider and unwelcome guest, Grendel, the ‘demonic prowler of the dark’, is enraged by the sounds of merriment coming from the Danes’ halls, pleasures that he will never be able to partake in due to his banishment. This exile from society has alienated him so much that he is driven to forcefully invading the Heorot and antagonizing his hosts. Grendel is portrayed as a manifestation of an anti-Christ character, another alias of Cain, who is consumed by his greed and jealousy of organized society. Not only is Grendel a slithering example of jealousy gone too far, but also a literal manifestation of the lurking enemies outside of the Danes’ windows: the constant fear of attack from guests who take more than they are offered. When Beowulf fights against Grendel in the battle to take back the Heorot, it is not just a battle of protection and honor, but also reinforces the fear of what could happen if we allow strange and foreign guests into our homes. In the end, Grendel’s role as a Risberg 3 snarling fiend in the story shows us the Anglo-Saxons’ acknowledgment of the destructive outcomes of envy. In the minds of the human characters, there are also allegories of man’s constant struggle with our own tendencies towards jealousy, such as Unferth’s speech challenging Beowulf’s exploits. “Unferth, a son of Ecglaf’s, spoke / contrary words. Beowulf’s coming, / his sea-braving, made him sick with envy”(lines 502 – 503). The indignant Unferth is extremely bitter and resentful of Beowulf’s accomplishments, and as such he is portrayed as ‘sick with envy,’ a negative depiction that shows us another fear of where envy can lead. Not only does this obvious jealousy make him a clearly defined antagonist but Unferth is also a known kin-slayer, the most evil crime that can possibly be committed in this ancient society. This mark of shame and his brooding verbal attack on Beowulf show us the recognition of monstrous qualities that are dreadfully prevalent in humanity. The next monster that expresses a Biblical sin, vengeance, is the lamenting mother of Grendel who is driven into a wrathful frenzy because of the murder of her son. Barely a day after the death of Grendel, his mother makes her appearance as an embodiment of devilish influences, seething with anger and desire for retribution: “But now [Grendel’s] mother / had sallied forth on a savage journey, / grief-racked and ravenous, desperate for revenge”(lines 1277–1279). Not only is Grendel’s mother portrayed as fanatical with anger beyond all hope of forging a truce, but also her desperation for vengeance turns her into a ‘ravenous savage,’ a creature totally Risberg 4 inhuman and terrifying that invalidates all of her human qualities, a monster beyond all hope of redemption. The Bible states: “You shall not take vengeance or bear a grudge against the sons of your own people”(Leviticus 19:18). Revenge in any form is not advocated by Christianity, yet it is rife amongst the overbearing human characters, such as Beowulf, and also the monster characters. Grendel’s mother does not spare even a minute before storming the sleeping Heorot and attempting to avenge her son’s murder. Grendel’s mother is not the only character in the poem who is guilty of this crime against Christianity; the Danes lose many beloved men when Grendel sieges their hall, and they also desire reprisal for their fallen. However, due to the beliefs of their warrior society that clash with Christianity, they have their own rules that justify attacks against demons. Beowulf claims that: “It is always better / to avenge dear ones than to indulge in mourning”(lines 1384 – 1385). The Anglo-Saxons see the reprisal that Grendel’s mother covets as foreign and malicious, the savage desire of a demonic, nonhuman enemy, which to them distinctly differentiates from their own desire to repay the deaths of their good kinsmen. They thought that her retaliation was unsubstantiated, while theirs was justified murder. This egocentric mentality effectively allowed the Anglo-Saxons to pursue their own fights by battling vengeance with vengeance. It was back-and-forth disputes like these that created intricate webs of unpaid debts between the warring pagan tribes, and Grendel’s mother represents another foreign threat hungering to collect its due that Beowulf thinks he needs to neutralize. Therefore, Christianity’s Risberg 5 claim that vengeance is a heinous crime was quickly welcomed by the Anglo-Saxons who had lost their loved ones to their own obsession with violent retribution. Grendel’s mother’s motivations are yet another instance of the poet illustrating the folly in pagan values, and he gives us a calamitous image of what vengeance really looks like. Finally, another aspect of pagan religion that plays a huge part in their lives and motivations is the possession of material wealth. The Bible states: “take heed, and beware of all covetousness; for a man’s life does not consist in the abundance of his possessions”(Luke 12:15). Christianity urges its followers to abandon their attachments to material goods, for the value of life is not measured by physical objects. The gold-hoarding dragon, however, exists solely for the protection of his earthly treasures, and when a single goblet is stolen from him, he is immediately frenzied with vehement disregard for human life: So the guardian of the mound, the hoard-watcher, waited for the gloaming with fierce impatience; his pent-up fury at the loss of the vessel made him long to hit back and lash out in flames. (lines 2302–2306) The furious dragon is a perfect example of the intent behind Christianity’s urge to let go of materials. The creature is so attached to a mere golden goblet that he is instantly enraged with the desire to violently lash out against the thief and anyone Risberg 6 who stands in his way as soon as the goblet is stolen from him. However, material wealth, according to Christianity, does not ascend with us to the next life, which means that the lengths that the dragon goes to only to protect his earthly treasures are a waste of his life and the lives of the innocents that he kills in his rampage. Beowulf, too, falls into the same trap of holding treasure in higher priority than his own life: “I shall win the gold / by my courage, or else mortal combat, / doom of battle, will bear your lord away”(lines 2535–2538). Although he does believe he is earning wealth to pass on to his people, Beowulf does not risk his life on the necessity of needing to save his men’s lives or to fulfill his duty as shield to his people. In fact, there is no evidence in the text that implies that he is required to fight the dragon at all; he fights the dragon solely for his own desire for treasure and glory, which are fallible rewards that, according to Christianity, will do him no good once he passes away. The ancient dragon that exists for nothing more than to protect his hoard is an exemplar of what could happen if someone took the pagan emphasis on wealth too far: an empty existence based on nothing but mortal objects that have no meaning in the Christian afterlife. The pagan societies place such a high value on material wealth that Beowulf ends up paying the ultimate price: the dragon claims his life, and the Geat people suffer for generations to come in his absence: [Beowulf’s] royal pyre will melt no small amount of gold: heaped there in a hoard, it was brought at a heavy cost, Risberg 7 and that pile of rings he paid for at the end with his own life will go up with the flame, be furled in fire: treasure no follower will wear in his memory, nor lovely woman link and attach as a torque around her neck– but often, repeatedly, in the path of exile they shall walk bereft, bowed under woe, now that their leader’s laugh is silenced, high spirits quenched. (lines 3010-3021) In a futile sacrifice, Beowulf robs the Geats of both the blood-marked treasure and their finest ruler through the loss of his own life. The narrator places significant emphasis on the Geats’ war-torn future to show the havoc that Beowulf’s covetous behavior brought to them. They will ‘walk bereft, bowed under woe,’ all hope for survival burned up with the body of their leader. Beowulf’s material-driven sacrifice results in no joy at all for his people, and the treasure he died for will never be worn by his people in his memory, for the objects that Beowulf sold his life for become useless as soon as he is no longer alive protect the Geats’ assets. The prospect of possessing treasure brings the Geats no comfort when they face the bleak, kingless future ahead of them; in fact, having the treasure would make them an even larger target for oppressors that desire to enslave them. Without a strong leader, the Geats are vulnerable to attack and certainly unable to protect themselves, let alone Risberg 8 safeguard a dragon’s hoard, all because of Beowulf’s selfish gamble with his life. Starkly contrasting with Christianity’s detachment from physical materials, the pagan obsession with material wealth leads the Anglo-Saxon communities into chaos and their own destruction. The loathing of pagan values like vengeance and materialism began long before Christianity was introduced into the feudal world. It began in tales like Beowulf, where the heroes fought against monsters that represented their own faults, and nonChristian codes claimed the lives of countless innocents before the ideals of virtuous commandments appeared instead of paganism. Although the monsters in Beowulf are described as sinister creatures that are inhuman and alien to the core, their motivations show us the internal struggles and fears that the Anglo-Saxons had about their own nature and reflect these fears in their behavior. The poet created these flawed antagonists as representatives of the Christian view on the pagan belief system, painting it as a religion of sinners and coveters, while all the time placing a sparkling crown upon the head of the Christian god by incorporating him into an evidently pagan story. Historically, Beowulf’s time period was followed by the conquest of Christianity, certainly due in no small part to the negative portrayals of pagan values in pieces of Anglo-Saxon literature such as Beowulf. Ultimately, the Anglo-Saxons embraced Christianity, which served as an opposite of the spectrum, a solution to the pagan system that their heroes, like Beowulf, were already fighting against in its most gruesome and tangible forms. Risberg 9 Works Cited Beowulf. (Translator: Heaney, Seamus). New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2000. The Holy Bible, Revised Standard Version. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1952. Risberg 10 Revision Statement: I have condensed the thesis into a single sentence to make it more concise and I have split up the two longest paragraphs into separate paragraphs. I have also totally revised the ‘wealth’ paragraph and made it more closely tie to the quote, how and what the Geats are losing as Beowulf passes away, etc. Finally, I have added a major theme to the conclusion paragraph that relates the conclusion to the poet’s motivation behind personifying the antagonists with pagan values. Lauren Risberg October 1, 2008 Ms. Stegmiller British Literature Beowulf Essay Outline -Are these monsters truly monstrous? Each monster represents a different aspect of humanity that we fight – Grendel = jealousy, Grendel’s mother = vengeance, the Dragon = desire for material wealth. GRENDEL – motivated by human emotions -Loneliness, jealousy P41 “he had dwelt for a time in misery among the banished monsters, / Cain’s clan, whom the Creator had outlawed / and condemned as outcasts.” Lines 105 – 108 “spurned and joyless,” line 720 “the dread of the land was desperate to escape, / to take a roundabout road and flee / to his lair in the fens.” “Like a man outlawed for wickedness, he must await the mighty judgment of God in majesty.” 976 – 979 “Beowulf in his fury / now settled that score: he saw the monster / in his resting place, war-weary and wrecked, / a lifeless corpse, a casualty / of the battle in Heorot.” 1583 “once death removed that murdering, guilt-steeped, God-cursed fiend” 1682 “Unferth, a son of Ecglaf’s, spoke / contrary words. Beowulf’s coming, / his seabraving, made him sick with envy” 502 - 503 Risberg 11 BIBLE: Galatians 5:26 says, “Let us not become conceited, provoking and envying each other.” Song of Songs (Song of Solomon) 8:6, says "jealousy is cruel as the grave: the coals thereof are coals of fire, which hath a most vehement flame." GRENDEL’S MOTHER – motivated by vengeance, just like the humans “But now his mother / had sallied forth on a savage journey, / grief-racked and ravenous, desperate for revenge.” 1277 – 1279 “Her onslaught was less / only by as much as an amazon warrior’s / strength is less than an armed man’s when the hefted sword, its hammered edge / and gleaming blade slathered in blood, / razed the sturdy boar-ridge off a helmet.” 1283 – 1289 “The hell-dam was in panic, desperate to get out, / in mortal terror of the moment she was found.” 1292 - 1293 “The bargain was hard, / both parties having to pay with the lives of friends.” 1304 – 1305 “And the old lord, / the grey-haired warrior, was heartsore and weary / when he heard the news: his highest-placed adviser, / his dearest companion, was dead and gone.” 1307 – 1310 (COMPARISON) “and now this powerful / other one arrives, this force for evil driven to avenge her kinsman’s death.” 1338 – 1340 “It is always better to avenge dear ones than to indulge in mourning.” 1384 – 1385 “So she pounced upon him and pulled out a broad, whetted knife: now she would avenge / her only child.” 1544 -5 “Death had robbed her, / Geats had slain Grendel, so his ghastly dam / struck back and with bare-faced defiance / laid a man low.” 2119 – 1222 THE DRAGON – motivated by treasure, was stolen from, only wants to reclaim what’s his. “a dragon on the prowl / from the steep vaults of a stone-roofed barrow / where he guarded a hoard; there was a hidden passage, / unknown to men, but someone Risberg 12 managed / to enter by it and interfere / with the heathen trove. He had handled and removed / a gem-studded goblet; it gained him nothing, / though with a thief’s wiles he had outwitted the sleeping dragon; that drove him into rage, / as the people of that country would soon discover.” “For three centuries, the scourge of the people had stood guard on the stoutly protected / underground treasury, until the intruder / unleashed its fury” 2280 “When the dragon awoke, trouble flared again. / He ripped down the rock, writhing with anger / when he saw the footprints of the prowler who had stolen / too close to his dreaming head.” Prowler – used to describe both the human thief and the dragon “hoard-guardian” 2295 “So the guardian of the mound, the hoard-watcher, waited for the gloaming with fierce impatience; his pent-up fury / at the loss of the vessel made him long to hit back and lash out in flames.” 2350 “Everywhere the havoc he wrought was in evidence. / Far and near, the Geat nation bore the brunt of his brutal assaults and virulent hate.” 2318 – 2319 “After many trials, he was destined to face the end of his days / in this mortal world; as was the dragon, / for all his long leasehold on the treasure.” 2342 – 2344 “I shall win the gold / by my courage, or else mortal combat, / doom of battle, will bear your lord away.” 2535 – 2538 “Roused to a fury, / each antagonist struck terror in the other.” 2564 – 2565 Hrothgar warns: “Choose, dear Beowulf, the better part, / eternal rewards. Do not give way to pride. / For a brief while your strength is in bloom / but it fades quickly; and soon there will follow illness of the sword to lay you low, / or a sudden fire or surge of water / or jabbing blade or javelin from the air / or repellent age.” 1760