NIJ Final Report - University of Delaware

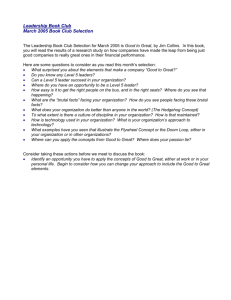

advertisement