Introduction - Georgetown College

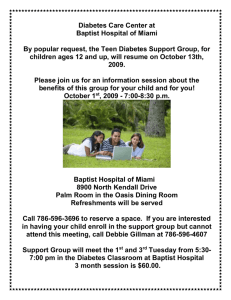

advertisement

Salvaging the Baptist Political Hermeneutic, Salvaging Racial Reconciliation by L. Andrew Watts June 28, 2008 Belmont University Nashville, TN Introduction In one early scene of Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, the protagonist of the novel simply known as the narrator speaks from a dark basement in a white-inhabited tenement lighted by one centered ceiling bulb whose electricity he steals. He tells the reader, before he begins to recall the events that led him to this cellar-prison, of a fight he once witnessed. He recalls: Once I saw a prizefighter boxing a yokel. The fighter was swift and amazingly scientific. His body was one violent flow of rapid rhythmic action. He hit the yokel a hundred times while the yokel held up his arms in stunned surprise. But suddenly the yokel, rolling about in the gale of boxing gloves, struck one blow and knocked science, speed and footwork as cold as a well-digger’s posterior. The smart money hit the canvas. The long shot got the nod. The yokel had simply stepped in side of his opponent’s sense of time.1 As one learns about the life of the narrator, the religious, political and social meanings of the metaphors of science, speed and footwork come into focus in the book. They are manifested in the legal and cultural racism of post-reconstruction America, a racism experienced by the narrator. They give form and shape to the very barriers Ellison describes above. These metaphors, if Ellison is right in his 1995 introduction to the novel, still function powerfully in 21st century America. They shape the fellowship of American Christians. Consequently, an initial question concerning black and white fraternity arises which drives this paper: could it be that when it comes to Christian reconciliation between the two, for baptist 1 Ralph Ellison. Invisible Man, 2nd edition (New York: Vintage Books, 1995), 8. Americans black and white both, there seems to exist a kind of theological “science”, a kind of discursive “speed” and a kind “ecclesial” footwork obstructing faithful koinonia. Not to take anything away from the Holy Spirit, but, in other words, could it be that baptist theology, discourse and ecclesial practice serve as the very topoi, literally “places” and liberally, patterns of meaning construction, where Christian reconciliation breaks down? This paper will suggest, following James McClendon’s lead in Witness, that baptist koinonia is sick. Given the weight of social data showing stark differences in the welfare of black and white lives in the United States, reconciliation between black and white baptists is in need of a good diagnosis. McClendon believes that the failure of baptist peoplehood has three causes: hermeneutical, cultural, and ecclesial.2 In what follows I will focus on the hermeneutical causes. I will examine the reading strategies practiced by black and white baptists. My interest is in the political or anti-political nature of both, What “thises” and “thats”? Why Baptist? Are not other types of Christians beset by the sin of racism? Plainly, a Baptist vision for koinonia exists. A Baptist vision for reading the story of Jesus and living faithfully in that story does indeed exist. It exists as Baptists as Baptists are caught up in the story of Jesus, or as Carlyle Marney stated matter-of-factly in The Recovery of the Person, as believers who are members of “the Holy and Blessed Trinity [as] the Father, the Son and the Believer possessed of and by the Holy Spirit.”3 It exists as Baptists are believers who have an eschatological role in Jesus’ story, which gives them a distinct but not exclusive vision concerning God’s redemptive action in and through Jesus. For this reason, the forms of racism 2 James Wm. McClendon. Witness: Systematic Theology (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 2000), 374. 3 Carlyle Marney. The Recovery of the Person (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1963), 151. 2 that function to divide Baptists are similar to those dividing other denominations, yet distinct as well. In this paper I will refer to EuroAmerican baptist heritage as the dominant tradition baptists, borrowing language from theologians concerned with race, gender and class. It is descriptive rather than prescriptive. In using dominant, I seek constantly to remember that white baptist theology, history and practice is caste simply as “baptist theology.” Following Will Campbell, I will also refer to racial reconciliation as simply reconciliation. This is neither a refusal to acknowledge the centrality of race in the separation of baptist, nor is it a naïve experiment in baptist race blindness. It is simply the recognition that a koinonia in disrepair is a theological problem. My burden, then, is to be consistent in maintaining that t what is ‘theological’ is also always racial as it a human work. Otherwise, I would perpetuate a tragic consequence of race blindness: race neglect. What is the Baptist vision? A first assumption established here is that baptists are those Christians who have convictions without which they would be different people, to paraphrase James McClendon’s often used definition of convictions. This assumption has been seen to be a positive description of baptist Christians in America, and indeed by the grace of Christ it has. Yet, it also describes the root cause of a baptist koinonia in disrepair. Following McClendon in his first volume, Ethics, the baptist vision pictured here begins with a lower case ‘b’. This is a broad reaching tradition: baptists with a little ‘b’ are Christians whose identity is construed through narratives that are historically set in another time and place but display redemptive power here and now.4 McClendon has in mind, primarily, the unity of Christians divided by formal causes: denomination or doctrine. The little “b” identifier pays attention to other 4 James Wm. McClendon. Ethics: Systematic Theology (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1986), 34. 3 differences, though and McClendon gives them deliberate attention throughout the three systematic volumes. He teaches us to be mindful that first and foremost, being a little “b” baptist means recognizing what Hans Frei, George Lindbeck, Stanley Hauerwas and Kathryn Tanner have recognized in their work, but what James Cone, Deotis Roberts, Martin Luther King and Will Campbell have known for a while, that what divides Christians cannot be neatly categorized as doctrine, custom, belief or conviction. What is a baptist hermeneutic? It is the “this is that” and “then is now” vision. It is the necessary and sufficient organizing principle for a little “b” baptist theology. 5 It serves as a “hermeneutical motto, which is shared awareness of the present Christian community as the primitive community and the eschatological community.” Barry Harvey explains the complexity of McClendon’s interpretive maneuver in his essay “Beginning in the Middle of Things: Following James McClendon’s Systematic Theology”, written shortly after the publication of McClendon’s third systematic volume, Witness. Harvey highlights the summative phrase, “that past, present and future are linked by a ‘trope of mystical identity binding the story now to the story then, and the story then and now to God's future yet to come’.”6 The best way to explain how this hermeneutic works, as Harvey notes, is through the analogy of the Catholic Eucharist, which serves as McClendon’s primary trope. Ultimately, the upshot of the “this is that” hermeneutical vision leads us to understand that, again according to Harvey, “One way of parsing this complex relationship between past, present and future is to say that the church does not simply have a hermeneutic for interpreting world and Bible, but that it is that hermeneutic.”7 5 McClendon, Ethics, 34. Barry Harvey. “Beginning in the Middle of Things: Following James McClendon’s Systematic Theology” in Modem Theology 18:2 April (2002), 261. 7 Ibid., 255. 6 4 Though more will be said about this vision below, and Harvey does so as well in his excellent essay, what I find intriguing in this vision is the link between interpretation and something other than the biblical text. It is a vision not only for how Scripture interprets Scripture, how Scripture interprets the church, how the church interprets scripture and how both interpret the world, but also it is a vision for how the church interprets itself. In fact, McClendon asserts the same: the “this is that” vision is a reading strategy sufficiently distinctive to enable us to interpret the baptist way of life by it.8 It follows, then, that we should look at the ways in which both dominant tradition baptists and black baptists interpret themselves. We should learn, as Harvey says, how they see themselves as a normative mode for Christian existence here in the middle. We are led to inquire, then, which “thises” and which “thats” for being baptist are norms? The baptist answer is, of course, all of them. African American baptists might object to this response, however. For example, different baptismal statements for blacks than whites circulating in northern and southern churches during slavery must be reconsidered as normative practice. Could it be that a hermeneutic of the baptist hermeneutic is a first order of business for reconciliation? Being dominant tradition baptist means living in a melee of normed norms. Prayers sometimes erupt in the middle of a fight service. For example, respected Baptist Historian Walter Shurden has a friendly conversation with the 1997 McClendon-influenced document, “Re-Envisioning Baptist Identity: A Manifesto for Baptist Communities in North America”. Of the Manifesto he comments, “…because of its studied, strained, and unfortunate de-emphasis on 8 McClendon. Ethics, 34. 5 the role of the individual, nonetheless fails to paint a balanced picture of the Baptist identity.”9 The authors of the 1997 document interpret the baptist tradition to be more communitarian, or more catholic. Shurden and the Manifesto authors read the tradition differently. For baptists, these small differences have no bearing on the common worship of a unified body of believers. At least, this is the hermeneutical position of dominant tradition baptists. Are there consequences for reconciliation in this hermeneutical norm of disagreement? The baptist ethic of toleration based in freedom is itself an indicator of one of the two fundamental hermeneutical barriers between the two churches: depoliticized identity and ahistorical fellowship. Toleration works as a contract with historical, social and political factors, both positively and negatively. More will be said about the contractual nature of the dominant tradition’s hermeneutic below. The upshot is, since rules of the baptist game are different for blacks than they are for whites, the two churches remain intolerably separated, not simply segregated. The way these dominant norms work can be seen in the work of many baptist scholars, including my own. David Gushee in his recent book The Future of Faith in American Politics spends time early in the text defining evangelical Christians. He explains that they share common beliefs, like “the final ultimate authority is the Bible,” that “Christ dies for the salvation of all,” and a belief in “engaged orthodoxy.”10 He later observes, based on social analysis in a very provocative book, Divided by Faith, that “this cluster of beliefs is equally applicable across racial lines. White and non-nonwhite evangelicals do not differ theologically in any significant Walter B. Shurden. “The Baptist Identity and the Baptist Manifesto” on Perspectives in Religious Studies, 25:4 Winter (1998), 321-340. 9 10 David P. Gushee. The Future of Faith in American Politics: The Public Witness of the Evangelical Center (Waco, TX: Baylor University Press, 2008), 18. 6 way.”11 Although Divided by Faith certainly gives data that reveals theological commonality between black and white evangelicals, it also reveals differences that are not simply the same theological perspective. Gushee seems to fall into this perspective as he posits a theological unity. But is it an artificial unity? It might appear that the questions here reveal questionable commitments to the postmodern condition of a plurality of truths. Yet, the point is significant. This kind of language reveals the barriers to reconciliation between white and black baptists in the United States, even as Gushee has carefully spoken in that text and other writings about African American sisters and brothers. Such language illustrates how the social and theological barriers are, as we shall see, constructed hermeneutically. White baptists have learned to read their own tradition from foundations and with methods which black baptist faith rejects in formal theological expression and in daily practice. One symptom lies in the way core distinctives are understood. Certain baptist distinctives are constitutive of the baptist identity. It follows, then, that how they function as rules for being baptist significantly affects the baptist body. How they function is revealed by the work that the language in which they are uttered does. African American theologian Vincent Wimbush reminds us that every discursive formation is political.12 Likewise, James Cone insists that God is a political God.13 A guiding image for this politics might be found in Jacquelyn Grant’s playful but tragic title of her critique of white feminist Christology, White Women’s Christ and Black Women’s Jesus. What is meant 11 Ibid., 18. Vincent Wimbush, “We Will Make our Own Future Text: An Alternative Orientation to Interpretation” in True to our Native Land: An African American New Testament Commentary, Brian K. Blount, general editor (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2007), 44. 12 13 James H. Cone. God of the Oppressed (New York: Orbis Books, 1997), 57. 7 by political? Is it the same meaning that contemporary baptist discourse shaped by the dominant white tradition intends—the culture(s) of governance, including partisan loyalties? Or does it look like the religious action of a young pastor named Martin Luther King, Jr., who in his first senior pastorate at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama in 1954 made registration to vote a prerequisite in the congregation? Cornell West helps us understand King’s action. He states that black theology claims that, 1) the historical experience of black people and the readings of the biblical texts that emerge form the centers around which reflection about God evolves; and 2) This reflection is related, in some way, to the liberation of black people, to the creation of a more abundant life definable in existential, economic, social and political terms.14 Interestingly, soon after he took up residence in Montgomery King earned his Ph.D. and the Montgomery bus boycott began. Richard Lischer tells us that after the boycott, King moved from the personalist idealism of Brightman to the realism of Niebhur. The political nature of black theology, the black church and its existence in a racialized society returned King to his roots, Lischer says. Once there, he engaged the specificity of race in all its meanings. This “sharpened the point of his biblical interpretation and preaching.”15 It sharpened his Christian witness. In addition, Dwight Hopkins directs us back to King when he portrays black theology as a “Christian movement of freedom for the transformation of personal and systemic power relations.”16 For Hopkins, the relations are the subject of a constructive and systematic black 14 Cornel West. Prophesy Deliverance! An Afro-American Revolutionary Christianity (Philadelphia: The Westminster Press, 1982), 107. 15 Lischer, 55. Dwight Hopkins, Linda E. Thomas. “Black Theology U.S.A. Revisited” in Journal of Theology for Southern Africa, March 1998:100, p. 63. 16 8 theology of liberation, comprising politics and culture, women and men, Christian and nonChristian, and church and non-institutional church.17 Nowhere is this seen as poignantly as it is in the association of the political world and the spiritual world in King’s preaching and speeches. As Lischer explains, King’s power of action lay in his power of interpretation of the state of the body politic.18 The interpretive norms for black theology are laden with the political. Difference matters. Race matters. In Katie Canon’s thought, black theology is human archeology. 19 Black theology and its hermeneutic perspective are political as the prophets of the Old Testament, Jesus, and the saints of the Black church are prophetic. This means, as Dennis Wiley writes, the black church must not only be committed to the poor and to service to the community, it must be one with the poor and one with the community.20 For a black hermeneutic to be described as politicized is to understand that in black theology, its subject includes the political as the whole of faith for black baptists: life in the church, the school, the plantation, the office, and the family because it negotiates, and continually sifts, power relations formed around the category of race. Dwight Hopkins. “Black Theology and the Second Generation” in Black Theology: A Documentary History, eds. James Cone and Gayraud S. Wilmore (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2001), 63. 17 18 Richard Lischer. The Preacher King: Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Word that Moved America (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995), 198. Katie Cannon. “Remembering what we never knew” in Journal of Women and Religion, vol. 16 (1998), 167 19 Dennis W. Wiley. “Black Theology, The Black Church, and the African American Community” in Black Theology, A documentary History, vol. 2, eds. James Cone and Gayraud S. Wilmore (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2001), 127. 20 9 White baptist theology has a similar hermeneutical tradition. For example, McClendon confirms that theology itself is political because of its dynamic structural character.21 Yet, the modern Western ethos produces an atomistic division of human life of discreet meanings. Abstract principles are sought out to explain history, principles whose meanings create division. That their meaning construction might be historically and theologically problematic due to the distance from the history they interpret cannot be developed fully here. However, some observations can be made concerning the existence of this method in dominant tradition baptist practices. For example, the reading strategy utilized by dominant tradition baptists to interpret the mark of religious liberty found its watermark in E.Y. Mullins famous phrase, “soul competency.” Mullins, educated in Southern Baptist doctrine and American individualism at the turn of the 20th century, positioned his famous principle under the “Religious Axiom” in the 1908 publication The Axioms of Religion. This axiom, he says, simply asserts the inalienable right of every person to deal with God for himself, and is “based upon the soul’s competency in religion.”22 Mullins further states that this axiom asserts the principle of individualism in religion. Although this principle does not exonerate one from duties to society, it does assert that the primary relation of religion is between God and the individual. Religious privilege and duty, he adds, subsist between men and God in the first instance in their capacity as individuals and only secondarily in their social relations.23 21 James Wm. McClendon. Doctrine: Systematic Theology (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1994), 50. 22 E.Y. Mullins and Herschel Hobbes. The Axioms of Religion, revised edition (Nashville: Broadman Press, 1978), 75. 23 Ibid., 76. 10 William Brackney notes that although Mullins’ phrase became the very essence of baptist identity for Southern Baptists, other baptists questioned it. Some like Brit H. Wheeler Robinson liked the concept but somewhat derisively characterized Mullin’s angle of approach as “naturally American.”24 McClendon himself says the phrase was framed too much in terms of the rugged individualism of pre-New Deal America to do justice to the shared discipleship that earlier baptists had embraced.25 Whether Mullins intended the emphasis on the individual’s exclusive access to God to have the unique life it has had for baptists is beyond the scope of this paper. It is my hunch that it would have, given the cultural milieu of the church in racist America at that time. We ask, then, through this phrase, did Mullin’s simply invest baptists in Troeltsch’s spiritualizing of the nature of the church?26 Mullins’ apparent separation of the liberty of conscience from the politics of its origin, be it the politics of governance or the politics of the church, has been read as one more statement in a strong baptist tradition of autonomous individualism against absolute governing authority. Yet, other baptists see it as an “infection of autonomous individualism” undermining absolute biblical authority.27 Ironically, both keep the autonomous individual intact, either as citizen or biblical exegete. At the time when Mullin’s penned the phrase “soul competency” to describe religious liberty, not only had the social, political economic and religious contexts of baptist life changed 24 William H. Brackney. A Genetic History of Baptist Thought (Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 2004), 409. 25 McClendon. Ethics, 30. Arne Rasmussen. “Historicizing the Historicist” in The Wisdom of the Cross (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1999), 232. 26 27 Al Mohler, Founders' Day address at Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, March 30, 2000. 11 from the worlds of Mullin’s theological progenitors. The rules of the baptist game had changed, as well. Although Francis Wayland inserted a rugged form of spiritualized individualism into baptist discourse 60 years before Mullins, Mullins might be said to be the final word on the depoliticized interpretation and practice of the concept of religious liberty. TO make the case, we should travel back to earlier baptists to hear what they had to say about religious liberty. Thomas Helwys, in The Mystery of Iniquity (1612), declares to James I that as monarch he has no authority over the immortal souls of his subjects. That Helwys seems compelled, furthermore, to communicate his Christian concern for the king who exercises authority reserved for God alone, is not surprising. This spiritual conscience in political clothing is consistent with the radical and English reformers. This concern, however, is more that a spiritual concern. It is political and material, arising in a day in which one’s baptism looked ahead to deep political consequences that would affect the entirety of one’s social existence. Helwys can view the situation no differently and communicates his concern by way of political analogy. He must, he says, “seek the salvation of the king although it were with the danger of our lives” just as “if we saw our kings person in danger by privy conspiracy or open assault we were bound to seek the kings preservation and deliverance, though it were with the laying down of our lives, which if we did not, we should readily and most worthily be condemned for traitors.”28 Treason is not only a moral failing but also a political crime of greatest social gravity. Religious liberty appears to bear upon not only upon the soul of the individual body, but upon the soul of the greater body politic as well. The concern for the king extends beyond his individual welfare to the welfare of society. Thomas Helwys. “The Mystery of Iniquity” in Baptist Roots: A Reader in the Theology of the Baptist People, eds. Curtis W. Freeman, James Wm. McClendon, and C. Rosalee Velloso da Silva (Valley Forge, PA: Judson Press, 1999), 84. 28 12 When John Leland writes nearly two hundred later in A Blow at the Root, he explains that liberty of conscience is “the inalienable right each person has, of worshipping his God according to the dictates of his conscience, without being prohibited, directed, or controlled therein by human law, either in time or place, or manner.”29 That the rights of the religiously formed conscience are inalienable because religion is a matter between God and individuals is argued also in The Rights of Conscience Inalienable (1791). There he invokes religious liberty as litmus against the Constantinian nature of Congregationalist Standing Order. Described by many as a Calvinist, his opposition to the kind of theocracy embodied in Puritan Massachusetts begs further research into his political theology. My interest concerns the interpretive frame for his defense of religious liberty. In The Rights of Conscience Inalienable, Leland argues for the inalienable conscience of a person within a broader argument that one’s religious beliefs should not exclude one from the social compact, as the Standing Order did. He argues that theocracies sinfully seek uniformity of beliefs, the exclusion of the best of men, and a distortion of truth.30 He unsubtly indicates that the religious conscience is a formidable obstacle to political tyranny. In fact, he argues that religion can and has stood apart from, and, being its own society, against the law. Could it be that Leland had a view of the church as a politics in its own right, which in its baptist form had assented to other political compacts? John Leland. “A Blow at the Root” in Baptist Roots: A Reader in the Theology of the Baptist People, eds. Curtis W. Freeman, James Wm. McClendon, and C. Rosalee Velloso da Silva (Valley Forge, PA: Judson Press, 1999), 174. 29 John Leland. “The Rights of Conscience Inalienable” in Political Sermons of the American Founding Era, 1730-1805, ed. by Ellis Sandoz (Indianapolis: Liberty Press, 1991), 1088. 30 13 Helwys and Leland are but two among many who emphasized liberty of conscience as a distinctive mark for baptists, whether particular or general. Questions need to be asked, however, at the correlation between the “this” of Mullins’ soul competency and the “that” of liberty of conscience as the two evolve in baptist thought through the 19th century. Curiously, if one compares the Philadelphia Confession, the New Hampshire Confession and the three Southern Baptist statements of faith coming after the entrance of Mullins, one finds a changed context for “liberty of conscience”. Each version of the Baptist Faith and Message—1925, 1963, 2000—states that “The state owes to the church protection and full freedom in the pursuit of its spiritual ends” as it warns the state neither to interfere nor privilege any one kind of church. The earlier documents contain do not contain this dualism, leaving instead religious liberty as liberty of conscience to be, as Helwys and Leland indicate, a loyalty to Christ rather than to government and a divinely given right to all rather than kings alone. Furthermore, the Philadelphia Confession (1742) confers the conscience, of which Christ is the sole Lord, into the hands of the magistrate as a political aid in living a “quiet and peaceable life, in all godliness and honesty (Chapter 25). In the same way the New Hampshire Confession (1833), with its milder Calvinism, links the conscience to political duties, maintaining that Christ is Lord both of the conscience and the prince. Is it possible that Mullins, considering his affinity for personal experience as a hermeneutical lens, reconfigures liberty of conscience into a depoliticized, individualistic freedom, either intentionally or unintentionally?31 Could it be that the mark of liberty of conscience came through 19th and early 20th century theological intellect in bad shape because of incomplete readings of the tradition? Is the kind of freedom liberty of conscience is a positive 31 Brackney. A Genetic History of Baptist Thought, 404 ff. 14 freedom, an outward focusing freedom of conscience that enables the body of Christ to seek the politics of Jesus rather than necessarily that of the state? Does its spiritualized meaning signify that current efforts to Christianize the state are just another form of statecraft that effaces the political essence of the reign of God? Stipulating “that” out of “this” Barry Harvey observes that McClendon’s baptist vision is one with which many congregations and associations in the free-church tradition would have little sympathy.32 At first glance one might assess that the “is” in the epithet “this is that” carries too much Catholic baggage. Yet, earlier Harvey observes that McClendon’s vision draws upon a form of figural and typological reading of scripture lost on modernity, using the Eucharistic “is” really only as a trope. Perhaps the offense of the reading strategy lies here rather than its Roman quality. Harvey explains that with his baptist hermeneutic McClendon posits here a most extraordinary (and no doubt controversial) thesis about time and history. The secular conception that animated the modern world and now haunts postmodernity depicted time apart from any relation to God and thus either as an empty container or channel (Newton) or as a formal condition, supplied by the mind, for organizing the sensible manifold (Kant). History according to either conception becomes a mere succession of happenings without connection, purpose, or goal other than the meanings we impose on a particular sequence of events, and the arbitrary nature of these impositions only serve to mock us with the capriciousness of our existence. What happened in the past is over and done with and therefore has no abiding claim over the present, and the future is little more than a domain to be conquered and colonized by human action that has no intrinsic relation to anything outside itself, and most especially to the presence of God. Harvey seems to be on to something here, something more than a descriptive assessment, for he highlights a tension concerning time and history that exists between the “this” and the “that” of the dominant tradition baptist hermeneutics. The implications of this tension for baptist 32 Harvey. “Beginning in the Middle of Things: Following James McClendon’s Systematic Theology”, 256. 15 reconciliation are disastrous. Baptists cannot escape modern, liberal views of history. Time and history have become non-relational quantities valued for their usefulness in understanding human progress.33 Slavery and the war that abolished slavery, though they are views as having paved the road to a just and egalitarian America, remain frozen in the cement of the past. Adonis Vidu explains the problem, identifying several liberal assumptions of history interpretation.34 (1) All discourses, including the theological ones, are historical; they can have no justification beyond a merely local and conventional warrant; they can make no claim on absolute truth. (2) The past, the tradition, and what it means for a theological discourse to be called Christian all have to undergo a certain amount of revision, while still keeping continuity with tradition. Vidu argues that liberal theologians look at tradition and conclude that what appeared to be privileged definitions of orthodoxy are nothing but interpretations that happen to have gained historical acceptance. Though they involve historical, cultural, and political decisions, they have no inherent claim on the heart of the tradition.35 Tradition’s discourses communicate meaning to its hearers only in so far as they mean something to them. This makes hermeneutics a process of contracting. According to political theorist Sheldon Wolin, many implications attend to a hermeneutic of contract. He explains, Michael S. Northcutt, “Being Silent: Time in the Spirit” in The Blackwell Companion to Christian Ethics, edited by Stanley Hauerwas and Samuel Wells (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2004), 415. 33 34 Adonis Vidu. The Place of the Past in Theological Construction in Theology Today, Col. 64 (2007), 205. 35 Ibid., 219. 16 The idea of a contract is familiar to us not only as a legal instrument by which most business transactions are negotiated but also as one of the archetypal metaphors of political theory. It is associated with such masters of political thought as Hobbes, Locke, Rousseau, Paine, and Kant. It has represented a distinctive vision of society, and nowhere has it been more influential, both in theory and in practice, than in the United States. It is a core notion in two of the most widely discussed political theories of recent years, those of John Rawls and Robert Nozick.36 Contract theory, he continues, conceives of a political society as the creation of individuals who freely consent to accept the authority and rules of political society on the basis of certain stipulated conditions, such as each shall be free to do as she or he pleases as long as his or her actions do not interfere with the rights of others. We could that another stipulation of a contractual political society is the freedom of belief as long as… Wolin explains that the contract way of understanding political life has been criticized for being unhistorical, as in giving a false account of how societies have actually come into existence. It assumes that “it is possible to talk intelligibly about the most fundamental principles of a society as though neither the society nor the individuals in it had a history.”37 Using the Genesis story of Jacob and Esau as a religiously authoritative trope, he imaginatively and clearly outlines a politics of contract. Moderns, too, like Esau have made it possible to contract away our birthright, its privileges and burdens, by forgetting its true nature and thereby preparing the way for its being reduced to a negotiable commodity with the result that its disappearance is not experienced as loss but as relief.38 Furthermore, the birthright we have made over to our Jacobs is our politicalness. Wolin’s definition of politicalness is not one government or political party identification, but is “our 36 Sheldon S. Wolin. The Presence of the Past: Essays on the State and the Constitution (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1989), 138. 37 Wolin, 139. 38 Ibid., 139. 17 capacity for developing into beings and know and value what it means to participate in and be responsible for the care and improvement of our common and collective life.”39 This means, he adds, that the historical things of our birthrights (he speaks of Americans) must be interpreted for their meaningfulness then and now, and this requires an interpretive mode that is able to reconnect past and present experience as construing political life then and now. Yet, the hermeneutical implications of a contract perspective become clear: to relieve individuals and society of the burden of the past by erasure.40 Or, in the theology of dominant tradition baptists: to relieve them of the costly practice of reconciliation. It has already been suggested, rightly or wrongly, that contemporary dominant baptist reading strategies are depoliticized in that they have misconstrued the baptist mark of liberty of conscience into a spiritualized competency of the soul. Now, we are concerned with the how of the what of the history. Following McClendon, I am suggesting that “liberty of conscience” functions like the rule of a game: it is constitutive of being baptist.41 As such, it is political, or it has a politicalness, because it moves us to participate pace Wolin in baptist, ecclesial and human collectives and it enables us to pace Harvey practice human community. 42 Yet, dominant tradition baptists have contracted out the deep political meanings of the distinctive liberty of conscience from their theology in part because of their ahistoricist, spiritualized view of the past. McClendon describes this hermeneutical error in Witness. There he locates this difference in how blacks and whites came to read the Bible differently. The “this 39 Ibid,, 140. 40 Ibid., 144. 41 McClendon. Ethics, 163. 42 Harvey, 221. 18 is that” double voice of African American interpretation of scripture is like W.E.B. DuBois’ “double vision” or double consciousness. Baptists of the little “b” type lost this double vision about the time of slavery, a time when historicist views of history froze redemption in the past, and when dispensational premillennialism bracketed the present for the future. He charges the historical-critical method with the loss of this double vision. Agreeing with Michael Cartwright he concludes that the existence of the difference in interpretation means that the two churches will not soon read scripture together.43 Consequently, the political actions that make intelligible the mark “liberty of conscience” have little bearing upon dominant tradition baptist peoplehood today. Now that the politics of believers’ baptism have been stipulated out of the baptist contract through soul competency, historic baptist freedom does different work. McClendon’s reliance on Austin’s speech-act theory grounds the explanation of why this is so. McClendon uses Austin to explain how the words we base our identities on form us. But Paul Ricouer helps us understand, also using Austin, how the actions on which we base our identities, or historical things as Wolin calls them, form us as well. His first significant point is that human action functions as discourse. It does so as more than a language-event or linguistic usage but still a speech-act, drawing on the work of Austin. Subsequently, human action operates in a sense according to the paradigm of the text, or the speech-act. As such, human action, as with written and spoken discourse, contains locutionary, illocutionary and perlocutionary force. The meaningfulness of an action has “propositional 43 McClendon. Witness, 375. 19 content that can be identified and reidentified as the same.”44 This is its locutionary force. The noema—the meaning—of the action likewise displays illocutionary traits as it becomes a paradigm for further action as “typology” and “criteriology” containing constitutive rules for further actions of the same meaning. Actions, too, as grounded in some circumstance with some actor and some intent, contain an essential condition without which the sense content of the action would be lost. “For example,” Ricouer says, “to understand what a promise is, we have to understand what the “essential condition” is according to which a given action “counts as” a promise. Consequently, just as written text “rescues” the sense content of any discourse from vanishing, a repeated action brings forward the meaning and sense content of the original action, yet in both instances the ideology of an absolute text or an absolute action falls away with the perlocutionary force—or the meaning of the speech-act or action on this or that hearer or actor. He concludes that a “meaningful action is an action the importance of which goes beyond its relevance to its initial situation.” 45 Consequently, an important action develops meanings that can be actualized or fulfilled in situations other than the one in which this action occurred, flowing the paradigm of written discourse, or the text.46 Reading for Reconciliation How then, can black and white baptists read together the tradition to reconcile koinonia in the North American baptist church? What reading strategy can step ‘inside of the time’ of a hermeneutic that depoliticizes liberty of conscience, relieving the conscience of its duty to examine racism in its form as prejudice and social structure? How can the histories being lived 44 Paul Ricouer. From Text to Action: Essays in Hermeneutics, II, trans. By Kathleen Blamey and John B. Thompson (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1991), 151. 45 Ricouer, 154. 46 Ibid., 155. 20 by African Americans now form the baptist church in a way that the histories of early baptists do not? And, how can dominant tradition baptists reclaim the actions of their forbearers, those noble and ignoble, faithful and sinful, as constitutive of the present church? I want to end with a concept, or vision, for interpretation borrowed from Mary McClintock Fulkerson: irruptive discourse. An irruptive discourse is one that: 1) destabilizes ‘given’ subjectivities through the destabilization of the social codes and power alignments inhering within certain discourses, 2) opens up closed discourses to scrutiny, confronting them with difference and perhaps dissonance, 3) engages the ideas, symbols, expressions and conventions of a discourse. It challenges the economy of meaning not for challenging’s sake, but for the sake of liberation from exclusion. 47 Furthermore, it is a discourse that is appropriately called, to use a term with a tired history in recent theological argument, intertextual. Remembering Ricouer, though, we should treat actions as well as language events as discourse. I believe Will Campbell serves as a contemporary example of such irruptive discourse. Campbell writes in Race and the Renewal of the Church that racism is first a theological problem, not a humanistic of sociological one, because it is sin. For Christians, the category of race must be refuted, a task Bonhoeffer seems to endow Christian ethics with doing in Ethics. The church cannot be concerned with racial reconciliation, but with reconciliation. Hence, the origin of my usage of reconciliation in this paper. A church that is solely concerned with racial reconciliation denies its own being on these premises.48 Moreover, since the racist and Mary McClintock Fulkerson. Changing the Subject: Women’s Discourses and Feminist Theology (Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2001), 355-360. 47 48 Will D. Campbell. Race and the Renewal of the Church (Philadelphia: The Westminster Press, 1962), 4-14. 21 segregationist are orthodox and sit in the church pew, only the Christian message as the message of Christ, rather than message of race, is required. But, of course, for Campbell, the message of Christ is a message about race relations, but one compelling on the gospel’s terms rather than the terms of economics, politics or sociology.49 Campbell seems to come precariously close to Francis Wayland’s 19th century baptist view of the status of the private individual before God, a contradictory view that led him on one hand to be an abolitionist of the slavery practices that contradicted this view, and on the other to reject any activism that would upset the Southerner’s same status as individual and slave holder.50 The primary category for discipleship for Wayland is the individual. Campbell too regards the individual—theologically given, that is—at the essential core of God’s reign. But Campbell seems not to mean, when he says that segregationists are those who regard a person from a human point of view like race, simply that those who address racist structures, or principalities, are battling windmills. To the contrary, he realizes that human sin has constructed real categories to which the church and its theology must respond, “This is no category of God.” The gospel replies to human structures as they are: sinful. Campbell has sought through his writings and stories, to show the church that it has become, as he reports P.D. East telling him in Brother to a Dragonfly, the Easter chicken church: just another chicken in the yard, having lost its Easter morning purple now looking like all the other chickens.51 Seen in the context of Campbell’s little “b” baptist vision, his willingness to risk and suffer political, social and 49 Campbell, 39. 50 Brackney, 259-269. 51 Will D. Campbell. Brother to a Dragonfly (New York: Continuum, 1989), 220. 22 religious ostracism has shaped his theological witness into an irruptive discourse, one that reclaims theology through avenues outside of theology’s home culture. Conclusion When “soul competency” made its way into 20th century Southern Baptist documents as guarantor of the spiritual work of the church, not only did the political meaning of religious liberty disappear, but also the ripples of a changed baptist fellowship were felt around the baptist, soon to include evangelical, world. We should heed Vincent Wimbush’s warning that “[E]very reading of important texts…reflects a reading or assessment of one’s own world.” Our world is one of contract in which individuals float restlessly and longingly for self-justification. It just might be the case that the dominant tradition baptist reading of the larger tradition cannot escape its methodological criteria of contract. This is the hermeneutical hinge, I believe, from which the political and the historical swing. Baptist freedoms have been cemented as stipulations for contracts: a contract with God, a contract with society, and consequently contract with black America. We have seen that black theology rejects a depoliticized view of the Christian existence as human existence in Jesus. To accept white contracts, to accommodate them, to align with them would be tantamount to saying, as Hauerwas accuses liberalism of saying, and believes Will Campbell understood well, “What’s a little slavery between friends?” Though the essence of reconciliation is forgiveness, rightly spoken by Greg Jones, I believe that perhaps dominant tradition baptists should seek forgiveness by way of repentance for their hermeneutic as a first sign of reconciliation. 23