High School Socialization Practices

advertisement

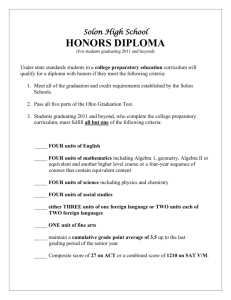

High School Socialization Practices and the Social Relations of Production: A Partial Replication of mid-1970’s Research by Danielle Schofield Abstract This replication of Dr. Shea’s 1977 doctoral dissertation on high school socialization processes was done to compare teachers’ responses to surveys completed at two different times (1977 and 1998). A questionnaire was given to 46 randomly selected full-time teachers at Amherst County High School. Of those, 43 percent responded. This research is based on the Bowles-Gintis correspondence principle. Their research supports the conclusion that schools socialize students to meet the demands of the occupations they will most likely pursue1. This questionnaire was designed to find out if teachers socialize students differently on the basis of different track assignments (college preparatory versus non-college preparatory). The results show that the majority of the fulltime teachers at Amherst County High School who responded to the survey, equally emphasize the same attitude and behaviors in both tracks. This is very different from the 1977 data, which had much more track-based variance among the responses. In the 1998 data the majority of teachers who responded reported that none of the classroom behavior problems listed were serious for either non-college or college-preparatory students. This also varies from the 1977 data, which had a much more wide variation of responses. Introduction The section that was replicated from Dr. Shea’s doctoral research on the Bowles and Gintis thesis is an important area of research. Academic tracking is widespread. According to the National Educational Longitudinal Survey, 86 percent of public high school students are placed in ability-grouped classes2. Tracking is a highly controversial practice, often criticized because it locks students into a particular track for an entire secondary school career. From a conflict theoretic perspective, “…education is directly linked to social stratification. Schools act as screening devices that limit occupational opportunities and reinforce social inequality.”3 Therefore this area of research is important in order to address the BowlesGintis thesis with empirical data, as well as to see if there have been any changes in teachers’ responses at two different time periods (1977 and 1998). 1 Bowles, S., and Herbert Gintis. Schooling in Capitalist America. New York: Basic Books. (1976). Mostellar, Fredrick, Light, Richard, and Jason Sachs. “Lessons from Ability Grouping.” Harvard Educational Review. (1996): 812-822. 3 Thompson, William, and Joseph Hickey. Society in Focus. New York: Harper Collins Publishers. (1995). 2 Methods After choosing what to eliminate from Dr. Shea’s original 135-item doctoral dissertation questionnaire, it was decided that we would use 43 questions from the original survey. It was also decided that, as with the original survey, we would send the teachers a five dollar check when they returned the survey. After permission was granted from the superintendent and the high school principal, the questionnaires were dropped off for the school secretary to put in the teachers’ mailboxes. Attached to the surveys, which were printed on light blue paper, were a cover letter, a consent form (printed on yellow paper), and a postage-paid white envelope addressed to Dr. Shea. Also included was a white envelope so that the teacher could write the address where the five dollar check would be sent. All these materials were enclosed in a manila envelope with the teacher’s name hand printed on the front. Results The results show that the majority of full-time teachers at Amherst County High School who responded to the survey teach more non-college preparatory (70%) than college-preparatory (30%) students. The data also indicates that the majority of teachers who responded equally emphasize the same attitudes and behaviors in both tracks (questions #316). The results also indicate that the majority of the teachers who took part in the questionnaire did not view the listed classroom behavior problems as serious for either noncollege or college-preparatory students (questions #17-26 and questions #30-39). Also, most of the teachers who responded believe that less than half of the students they have taught (this includes both non-college and college-preparatory students) will become either professional-managerial, clerical-sales, or blue-collar employees (questions #27-29 and #4042). Though, 68.4% of the teachers responded believe schools have a strong obligation to prepare students for future work (question #43). In addition, 55.6% of teachers who responded believe it is not serious for either non-college preparatory students or collegepreparatory students not to hand in homework, and 65% equally emphasized conformity to time schedules and regulations in both non-college and college-preparatory classrooms. It must be pointed out that the data results are insignificant, due to the small sample size. A small sample size, such as this one, which was twenty cases, produces a problem called cell frequency attenuation. In other words, there are too many cells for such a sample size. When there is an expected frequency fewer than five in each cell, the computer cannot do a statistical analysis of such small numbers. To remedy this problem, we would need a much larger response rate. Discussion The majority of the teachers who responded to the survey equally emphasized the same attitudes and behaviors in both college-preparatory and non-college preparatory students. I found this surprising. In the original survey, there were much more variance in the responses. For example, in the 1977 data, 100% of the teachers answered that they emphasize “ability to take initiative” more with college preparatory classes. In the 1998 data, 65% responded that they emphasize this characteristic equally among non-college preparatory and college preparatory students. The difference in responses could be due to the possibility that in 1998 there is much more awareness of the potential ill-effects of tracking than in 1977. In the last 20 years there have been numerous studies on the inequalities of tracking. The trend now in many schools is to “de-track” and lean more toward cooperative learning. Therefore it is possible that teachers are aware of the research on tracking, and they answered with more socially desirable responses. It is also probable that the differences between college-preparatory and non-college preparatory classes are not as pronounced as in 1977. One teacher wrote on the survey that they were not sure which students are college preparatory versus non-college preparatory. The majority of teachers who responded to the survey answered that the problems listed in questions #17-26 were not too serious. For question #23, 63.2% answered that it is not serious to hand in homework late. In the 1977 data, 5% thought it was not serious. It is possible that in the 1990’s, these problems listed in questions 17-26 and 30-39 are seen as “not too serious.” Perhaps teachers view weapons, drugs, and gangs as serious problems whereas in 1977, “late for class” was seen as more serious because weapons, drugs, and gangs were not as prevalent then as they are today. For question #27, 5.3% of the teachers who responded to the survey answered that more than half of the non-college preparatory students will become professional managerial employees (73.7% thought less than half would). In comparison, on question #40, 26.3% of the teachers who responded answered that more than half of the college preparatory students will become professional and managerial employees. This is surprising when compared to the last question (#43), which asks if the teachers believe the school has any obligation to prepare students for the kinds of attitudes and behaviors that will help them perform well in their later occupations: 68.4% of the teachers who responded, answered “Yes, I strongly believe the school has this obligation.” Teachers strongly believe that a school has this obligation, 5.3% believe more than half of non-college preparatory students will become professional managerial employees, and 26.3% believe that more than half of college-preparatory students will become professional and managerial employees. Yet, the majority of the teachers emphasized the characteristics in questions 3-16 equally with both sets of students. There appears to be a discrepancy: Teachers emphasize the same kinds of attitudes and behaviors for both college prep and non-college prep students, yet they believe more college prep students will become professional and managerial employees. I wonder whether the majority of teachers who responded gave more socially desirable answers. In the 1977 data, there was more variance in the responses for student characteristics emphasized by teachers (questions 3-16). For question #27, 2% of the teachers who responded thought that more than half of non-college prep students would become professional and managerial employees. For question #40, 21% answered that more than half of college-prep students would become professional and managerial employees. The 1977 data supports the Bowles and Gintis thesis that schools socialize students differently on the basis of their socializers’ (teachers’) beliefs about their future occupations. The data from 1977 and 1998 are similar for questions on students’ future occupations, but differ widely on student characteristics that teachers emphasize. My interpretation of the 1998 data is that if teachers equally emphasize student characteristics for both non-college and college-preparatory students, then the beliefs about their future occupations would be more alike than the percentage obtained. Limitations There are several limitations of the research. One is that we had a substantial nonresponse rate. We received only 20 surveys (43%) out of the 46 that were distributed. Some of the responses were close to percentage. This small difference raises concern that, if there was a high enough response rate (at least 60%), the outcome could have been different. Another limitation is that there were several surveys distributed at Amherst County High School around the same time. Another factor that could have limited our response rate is that the questionnaire was given out at the end of the school year. Perhaps because of time restraints, teachers did not fill out and return the survey. Another factor that could have hurt our response rate, is that the first question asked what subjects you have taught in the past school year. Perhaps some teachers did not fill out the survey because this question is a self-identifier. The cover letter was addressed with only the last name; some might have been offended that they were not addressed as Mr., Mrs., Miss, or Ms. We also did not use “live” postage on the return envelope, and perhaps some of the teachers were put off because it was too business like, rather than more personal. There is also the question of whether some of the questions asked on the survey are applicable anymore. It is possible that some of the questions are out of date. For example, the question (#17 and #30) that asks whether it is serious if students leave their seats without permission while the teacher is out of the room. According to some of the teachers’ written responses, it rarely happens that a teacher leaves the room, for fear of students getting hurt. If this research were to be replicated, it might be necessary to revise some of the questions. It would also be wise to distribute the survey not so close to the end of the school year. Since the responses in this study were not as different on the basis of track as those in the 1977 study, it might be beneficial to conduct some classroom observations, to see if teachers really emphasize student characteristics equally in both tracks. Of course there would have to be at least a few observers to double-check the observations.