THE GREEK MYTHS

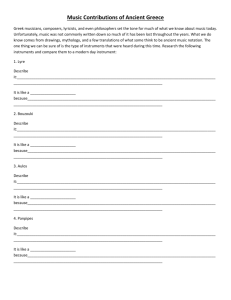

advertisement

THE GREEK MYTHS

Greek Mythology as Historical Tradition

William Harris, Prof. Em. Middlebury College

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

PREFACE

This book investigates the Greek myths as a thinly cloaked chapter in an ancient Historical

Tradition, which goes far back into the history of the Near East. A captious critic of conservative

cast might call this approach Cultural Materialism, while many who have read and loved the

Greek stories as highschool students will resent a theory which threatens the pleasure of the days

when they were entranced with their Bulfinch's Mythology. The Myths themselves have no real

basis in a Greek "Theology", which never was developed at any period.. The Mystery Religions

which coursed through Hellenic culture from Homer to Christ were the real "Religion" of the

Hellenic world, but their myths which were secret are ill known and generally had small influence

outisde the cults.. But the Myths do have many traces of historical fact, much of it going back to a

Pre-Greek period, even into the third millennium BCE. Examining these considerations will be the

core of the twelve chapters of this study.

The ancient Greek myths are a familiar part of the intellectual background of Western society.

Along with the materials of the Old Testament and New Testament, Greek mythology supplies a

variety of names, situations and awarenesses which no educated person can ignore. Reading the

Greek and Roman literary Classics, one is constantly confronted with mythological references,

and this is equally true of our English Classics, which from the Renaissance on used Classical

mythological names and references as a part of the modern Western cultural tradition. The Greek

and also the Hebraic traditions did contribute many of the views and traditions which crystallized

in the mind of modern Western society. But it was from Charles Bulfinch's popularizing book (The

age of Fable, l855) that Greek mythology became a part of the English language consciousness,

while mythical motifs reappeared indirectly in painting, sculpture and the curious Greek Revival

architecture in America. Even now elementary school classes learn the more common stories

about the Greek gods, especially those which present material consonant with our society's

esthetics and morals, while the less attractive tales of incest, murder and cannibalistic atrocities are

conveniently avoided.

For the Romans the Greek myths were readily available, and since they reflected the values and

status of the literary models of the Greek world, they were often used for largely illustrative and

decorative purposes. We see a fascination with the Greek stories in Ovid's and Propertius' poetry,

but sheer proliferation of mythologizing tends to become an end in itself. Mythological

"references" in Propertius are often nothing more than literary "asides" for the recognition of an

educated class of readers, while the poet's value lies more in his personal and subjective processes

than in the mythological trimming.

For earlier authors Aeschylos and especially Pindar, the myths were intertwined with the poet's

meaning in an inextricable interplay of forces, but already in the Hellenistic period and especially

in Alexandrian circles the Greek myths were either reference points for new treatments of

traditional themes, or used for purely decorative effects. By the time Apollodoros' Library of

Mythology was put together about l50 B.C. for literary readers' use, the myths had become a web

of stories which had lost both religious and historical significance. When the Roman learned his

mythology out of Julius Hyginus' strange little abridgment in Latin, he was familiarizing himself

with materials which he would find useful in his Classical reading, much as the modern student of

literature uses his pocket dictionary of mythology to decode Milton's Paradise Lost or the Greek

Drama which is on his reading list.

When one compares Greek mythology with the myth cycles of the Indian tradition, one sees

immediately that there is a vast difference between the two. The Indian myths have as wide a

story-telling range as the Greek myths, but they have also been incorporated into, and also formed

by a strong religious tradition. They are used to develop philosophical points, to indicate moral

choices, and to reinforce sincere religious views if value to the society. Part of the reason for this

transparency of purpose lies in the fact that there is a continuous religious tradition which extends

with many changes from Vedic to modern times, even as Hinduism became fused and

amalgamated with Buddhism, to reappear later as the dominant religious system of India. Within

this long, living tradition the position of the myths in India is full of new developments but their

use is relatively stable and clear.

Working with the Greek myths carefully, I have always felt that they are far more History than

Storytelling. Their theological and philosophical content is questionable and can often seem

evanescent. We do know the Greeks were early in contact with India by the 7th century BC, and I

believe some thoughtful Greeks absorbed some of the format of the Indian myths while entirely

missing their religious and philosophical penchant. But most of the the Greek myths reach further

back into the history of migrations into Europe from the Near East, and represent a different

segment of historical evolution.

I and many others have found the mythic interpretations of Joseph Campbell misleading and

embarked on an entirely wrong track. But Campbell achieved a certain degree of public fame in

the decades before his death. I feel we should not leave the public with an impression of Campbell

as the major authority in this area. Campbell started his studies with serious interest in the Hindu

myths, which are remarkable examples of myth, story and philosophy rolled into one. But then he

returned to the Greek materials, with a conviction that they were analogous to the Indian corpus

and throughout his long career he preached the message of the Indian doctrine on very different

Greek social and textual grounds. It is no pleasure to discredit Campbell under the adage "Nihil de

mortuis nisi malum...", but his loose and uncritical treatment of Greek myths as a close cousin of

the Indian mythologies, which has become popular in the last few decades, has led us on an

entirely wrong path.

The Greek myths had no regular religious structure or "Theology" to reinforce popular belief,

since Greek religion never became institutionalized beyond the needs of the individual city-state.

Myths became formalized and politicalized after the fifth century, and in the Hellenistic period

they became more of a political or even literary tradition than a religious phenomenon. It was the

ancient Mystery Cults which were the real religion of the Greeks, from the time of Homer down

into the Hellenistic Period, even with some features which were absorbed into early

Christianity.The myths were reduced to a complicated system of formalized storytelling, largely

bereft of historical and the earlier pre-Greek associations. Greek mythology turned into a

formalized political apparatus with specific associations and rituals assigned to each city-state, but

it could also be used as entertainment for a literary Hellenistic society. It is in this mode that it

appeared in Bulfinch's l9th century translation as a delightful set of stories from the ancient world,

arranged,compacted and regularized for modern readers.

Beyond being entertaining and useful for understanding the Classics read in translation and our

older English poetry, what do the Classical myths tell us? Often their meaning is obscure,

contradictory and (if taken literally) frightening. One might well ask if there is another way of

approach. Euhemeros, a Greek writer on myth and mythic history in the early third century B.C.

had already suggested an alternate path of interpretation for myths, his views were widely known

in the ancient world, and the fact that he did develop a new method of approach shows that even in

the Classical period people were not satisfied with the traditional, story-cycle approach to

mythology. His methods were of a sort that educated Hellenistic Greeks could understand and use.

His ideas enjoyed a considerable vogue in the Hellenistic world, although their extension was

limited by the accusation of atheism which was leveled against their founder. In the Christian

period Euhemeros' theories were used in another way, to demonstrate the man-made and hence

harmless notions of the Greek gods, and his notions became a stock demonstration of the futility

of the heathen world's atheistic theology.

In the last two centuries we have learned a great deal about man's behavior from the formal fields

of sociology, psychology, political science and economics. Archaeology has thrown a whole new

light upon man's recently unknown past, while anthropology has broadened the scope of all

studies of the human condition. Scientific aids, such as carbon-dating methods and pollen

identification, as well as information gathered by students of the history of science, have extended

our range of inquiry far beyond what the ancient Greek could have imagined. This "new thought"

must be present in any serious study of humankind, and much of this material is so important and

pervasive that it simply cannot be ignored. Our study of Man's history extends from the very

beginning of humankind some five millions years ago, to the time after the last glacial retreat,

when much factual material about the rise of civilization as a social phenomenon starts to appear.

A great deal of light on the human condition can be elicited from the rich matrix of human history

interpreted in the light of the newly evolving disciplines, and it is in this spirit that the present

study of Greek mythology is undertaken. Euhemeristic interpretation of myth has much to work

with in conjunction with modern studies of myth as part of the human social and historical record.

The Greek myths are of two sorts. Some are what can be called the "mythic" myths, which are

stories which find ways of telling important things about difficult and even ineffable matters

through stories. Some of the Greek myths explore profound matters and have through the ages

challenged people with examples of serious thought, these are the true and spiritual myths, which

abundantly deserve religious and philosophical study, and constitute to a major section of Greek

thought.

A second much larger group may be called the "historical" myths. These are the ones which

Euhemeros identified and began to interpret, and it is these which the present study will discuss.

Many of the myths, when viewed as mythology will seem confusing, self-contradictory and

somewhat pointless as myths, but this is because are historical records of social and historical

events which lose their meaning when read as quasi-religious mythology. And when the historical

mythology loses its original social and historical factuality, it becomes inane and superficial. Over

the years it has become common to tell and retell the myths as imaginative stories, leaving

historical origins aside, rather than trying to fathom an original meaning.

A partial parallel may be seen in the fossilized Mother Goose stories which date from l8th century

England. Children and their elders still enjoy telling and retelling the traditional tales about Jack

and Jill, Humpty Dumpty, and the old lady who lived in a shoe, but most of us have no idea of

they mean, if they do mean anything. Historical studies have shown that these stories once had

pertinent, often trenchant political meaning, but for most of us, they are amusing but essentially

meaningless. Yet by being familiar and historically "indestructible", they do form a part of our

cultural baggage, meaning left quite aside. We can enjoy the mouse who went up the clock,

without having any idea of what he was doing and that the story means. Appreciation of most of

the Greek myths is exactly of this nature, we know and retell and enjoy Greek mythology without

having much idea of what it is really about.

The germ of the idea behind the present study goes back to Euhemerus, a writer on mythology

who flourished about 300 B.C. at the court of Cassander, the king of Macedonia. Very little is

known about his life, even the place of his birth is disputed, the date of his death is unknown, and

there are no personal particulars to give us a better idea of the man. He is known chiefly as the

author of a book called The Sacred History, which purports to be based on inscriptional material

found on the island of Panchaea while traveling around the coast of Arabia Felix. These

inscriptions have never been taken to be any more real than the imaginary island of Panchaea, but

the Sacred History also outlines the theory for which Euhemerus' name is famous. Euhemeros

seems to have picked up some parts of his theory of interpretation from eastern sources which he

heard of on his travels, but some parts of his theory may come from Greek sources, or even from

his own imagination.

This study proceeds with an analysis of the Greek myths partly analogous to Euhemeros' outline.

His scant material has been collected by Nemethy (Euhemeri Reliquiae, Budapest l889), as a

source of what later became the Euhemeristic school of interpretation of the Greek myths. His

suggestions seem perhaps hesitant or tntative, either because they were not well developed in

ancient times, or because our historical information about them is so fragmentary. This study will

graft onto the Euhemeristic rootstock, a number of concepts and sources of information which are

available at the present time. Using Euhemeros' original and authentically Greek interpretations as

a starting point, we can go a great deal further than he would have gone, probably further than he

could have imagined.

Some of the inscriptions Euhemerus cites claimed to have come from Greece proper, others from

"Panchaia" which may be as far away as Ceylon (Sri Lanka). The Sacred History has never been

taken seriously as a document, but a full and entertaining description of Euhemerus' travels among

the Panchaeans is found in Diodorus Siculus (V, c. 4l-46), which at first glance might seem to

belong somewhere in the imaginative range between Psalmanazer's 1702 description of Formosa

and Gulliver's Travels. But we have more skills these days about processing of presumed "fake"

data for bits of fact, enough perhaps to make rereading the Sacra Historia worthwhile, if it is

undertaken by someone competent in ancient Near Eastern history.

One may wonder why Euhemerus was traveling in the Near East in the first place. He was

authorized to travel there by Cassander who found himself passed over after Alexander's death as

ruler of Macedonia, a position which he clearly expected not only because he was ambitious, but

also since he had married Alexander's half-sister Thessalonica. After killing Alexander's son

Alexander, and Alexander's wife Roxana, and making connections with various powers, he did

finally become ruler of Macedonia in 30l, just four years before his death. Everything that

Cassander did, seems to have been done in opposition to Alexander. He worked against

Alexander's family, against the assignment of rule in the empire, and he even rebuilt Thebes,

which Alexander had previously razed. Hence it is not surprising that the chapter of Alexander's

history, his trip to the East and specifically to India, should have been the one thing which

Cassander could not equal. When he sent Euhemerus to the East on an exploratory

cultural-historical mission, he probably thought he was ensuring for his memory the kind of fame

which Alexander had accrued in his lifetime as world-king in Greece and abroad.

Euhemerus' name would have probably been consigned to the library files of antiquity forever, had

he not incorporated in his writing the one idea which made his name famous. He maintained that

heroes and gods were actually men of note, who were commemorated for their achievements by

being relegated to divine status by a grateful populace. It has been suggested that this idea was

drawn from Indian or Arabian sources, which Euhemerus may have picked up in his travels either

from written materials or from discussion with the natives. Whatever the origin of this singular

idea, the ancient world fastened onto it with great interest, since it promoted a train of historical

thinking about the gods and heroes which few people in Greece had contemplated.

Euhemerus' theory proposed that the divine and semi-divine personages of myth were just people,

perhaps remarkable people, but actually humans and not of divine origin. For some people

Euhemerus was considered an evil man, oras the poet Callimachos put it "an idly babbling old

man", or still worse, an atheist, although for Hellenistic scholars his name was not identified with

atheism.

But the Christians took an opposite tack. If one could prove that the gods of antiquity were mere

human fabrications, whether they were so constructed for bad or for good reasons, Christians can

get rid of the weight of millennia of pagan thought with one swift stroke. This is rendered even

more plausible when it is suggested that Euhemerus himself was an atheist. From this odd notion

comes the important flow of Christian comment and quotation on this author, to which we owe a

great deal of our knowledge of Euhemerus and his theories. A great deal of this material is

hopelessly garbled, not only because of slanted arguments which the Christians were using, but

also because they had almost no authentic material at hand on which to base their views.

Second-hand historical criticism, especially when done with a zealot's vengeance, is not a good

source for exact information, but this is exactly the case of the many Christian apologists who

rehandled Euhemeros' name in the interests of proving old errors and establishing the true faith.

In l889 Geyza Nemethy brought together everything that is known about Euhemerus (G. Nemethy:

Euhemeria Reliquiae, Budapest l889), and this material was carefully sifted through by Jacoby in

his article on Euhemerus (Pauly Wissowa s.v. Euhemerus). Much of the ancient material is thin

and disappointing, especially when one considers the serious studies in the Euhemeristic spirit

which have been undertaken since the l8th century, starting with Banier's "Explication de la Fable,

Expliquee par la Histoire ", the l9th century factualizing historians and even the sociology of

Herbert Spencer.

Cicero intelligently remarks that "Those who maintain that famous and important men after their

death became the gods to whom we pray and bow.... are these men not actually immune to religion?

This kind of thinking has been developed by Euhemerus, which our Roman Ennius later translated

and interpreted. But it is Euhemerus who has portrayed the deaths and burials of the gods. Does he

(Euhemerus) seem on the one hand to have provided a factual base for religion, or has he actually

removed the need for it?" (Cicero De Natura Deorum I 42).

One wonders why, with all the rich Greek literary materials available, the 3 c. BC Roman poet

Ennius chose to translate the work of Euhemerus. It may have been that the Romans were uneasy

with the superior status of the Greek deities as compared to their own familiar if shadowy

Animistic spirits, and wanted an explanation which rendered these distant theological concepts

more understandable. If they turned to debunking them by analysis, it suits well the hardheaded,

practical Romans, who were at work developing a few things on their own, like Rustic Comedy

and the genre of Satire. Most people in the third century B.C. would still have been aware of the

subtleties of the old Roman animistic beliefs, which carried their own interpretation for a

perceptive country folk . If the Greek gods and heroes were not interpretable, they would seem

inaccessible, and in such a quandary Ennius' interest in approaching Euhemerus' doctrine seems

reasonable. Since Ennius' translation with his own commentary has disappeared and is known

only from slight references, there is little more that we can draw from this source.

Sextus Empiricus is not the best witness for subtle thought, he is as often disappointing in his

remarks about early Greek philosophical figures as he is informative. But in the case of

Euhemeros he is the only source which gives a clear and unequivocal statement of his basic views,

and his remarks can serve as a general introduction to Euhemeristic thought:

"In the days when life was unsettled, those who were superior to the others in strength and

intelligence, so as to get greater control over the rest (figuring that they might seem more

remarkable and serious), fabricated the story that there was some surpassing and, as it were, divine

power about their persons, and it is from this that they were venerated by the people as gods."

This is an extension of the rule of "man is the measure of all things", to the role of "measure of the

gods". Man made the gods, and in a typically Greek mode, made them out of human forms and

notions, and even eventually from human beings who had died. Xenophanes had said in parallel

spirit some centuries earlier "if oxen and lions had hands which enabled them to draw, they would

portray their gods as having bodies like their own, horses would portray them as horses, and oxen

as oxen". Moreover he noted "Ethiopians have gods with flat noses and black hair, Thracians have

gods with blue (glaukos!) eyes and red hair." With such well known statements serving as

intellectual background, Euhemeros' words would not have been surprising to the educated Greek

public. However he does, as Cicero remarked, work this process in reverse, and the results of his

theorizing can finally dispense with deity altogether.

In the history of the West after the Greek period, divification is common. It started with the cult of

Romulus and the Roman founding fathers, who are not actually deified, but given a special

position of respect and veneration in the Roman consciousness. The serious tone in which the

Augustan poets speak of these early heroic figures at Rome marks a semi-religious sanctity which

verges more on the religious than on the historical side. The formal divification of Caesar and the

Roman Emperors follows easily from Greek myths, from the old idea Eastern Monarchs were

gods in their own right, and from the old Roman hero tradition. As Christianity gathered strength

and numbers within the Roman world, it too found the practice of sanctifying certain holy men

with the title of "saint" to be a useful focus for public veneration. The transition from humanness

to godliness seems easier to imagine than the conversion of a god into a human being, which can

only be done as aa temporary disguise. Holifying famous men produces hallowed examples of

holiness out of human fabric, and this probably offers a greater opportunity for social

identification than the gods who reside apart in the clouds like Epicuros' "reformed" deities, aloof

and unconcerned.

The very familiarity of a great deal of Greek mythology, which was heavily used in a borrowed

form by everybody from the Romans to the classically oriented nineteenth century, obscures the

fact that many Greek myths are obscure in themselves, and so heavily reworked into later fabrics

that the basic meaning of the original cannot be imagined. But following an Euhemeristic thread,

and weaving it into the fabric of modern studies of the three pre-BC millennia which are now

appearing, we may elicit from the Greek Myths a wealth of surprising information.

In summary, the aim of this study is to bring into focus the Greek myths of the class which belong

less to a religious than to a historical class, and to elicit from them where possible,factual social

and historical meaning. There is much important information which we can draw from myths if

we treat them as carriers of the social and historical activities which were current in the early

Greek and pre-Greek periods, at the time when story-cycles (later to become myths) were alive

and responsive to social issues. In the last two hundred years we have learned a great deal about

man and his early history. If we can use a portion of our modern, multifarious frame of reference

in the interpretation of Greek myths, we can extend our knowledge of man's earlier history

considerably further back into the shadowy realm of Pre-History.

Chapter 1

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------The Heroes and Heroic Deeds

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------The world we live in is the natural frame or reference for our views, since our lives are passed in

close physical association with others, and we work closely with other people as the normal

function of urban living, which is now almost synonymous with the idea of civilization. It is

natural for us to see other human beings, whether in the past or present, as social animals, Aristotle

put it just that way, and for him, living in Greece in the fourth century B.C., the term was perfectly

well suited. But as we roll back the curtain of Greek history into Homer's time, and into the myths

which themselves reach into remote prehistory, we find a considerable list of important personages

(called Heroes) who do remarkable deeds, and are in every way worthy of admiration, except for

one thing: They have almost no capacity for integrated social behavior. When Diomedes in the

Iliad says,"This I learned from my father, always to seek after super-excellence (arete), and to be

superior to others... ", he a speaks of a world in which the individual is still the protagonist on the

human stage. He works alone, wins fame alone, and usually dies tragically, without the comfort of

family or solace of progeny.

What we call Civilized Man's history dates only from the period of the retreat of the last glacial

cold, after which time by crossbreeding and selecting certain strains of grasses, which were

eventually to become the grains as we know them, he made possible a greatly expanded human

population is needed, which in turn depends on a greatly expanded food supply. In order to

manage this, large numbers of people were need to plant, tend, harvest and finally store the

relatively non-perishable grains, thereby extending life through the non-growing winter months in

a secure manner. Whether the grains were evolved in response to larger population, or the

population increased because of the availability of the grains, is not clear, and this may ultimately

be something of an academic distinction. We know that both things happened about the same time,

and neither would have occurred without the other. The major discovery of this period was

certainly the realization that concerted, social behavior, probably with a great deal of organized

control from a ruling class, ushered in the larger social groups which we know as the ancient

kingdoms of the Near East and the Indus Valley. Without social interaction none of what we call

"Major Civilization" would have been possible.

On the other hand, ninety nine percent of man's known history was passed in the hunter-gatherer

stage, iin small social units of family, extended family and tribe. Within this pattern, the individual

hunter who works alone has a sure niche of identity. To expect that old patterns going back

hundreds of thousands of years should immediately fall into line with new social demands, and all

this in half a dozen millennia, is unreasonable. One of the important messages which we can read

in the Greek myths, is that most of the great heroes had a such a strong preference for working

alone that they were virtually unable to engage in regular social interaction with their peers. In fact,

heroes can never have peers, since they believe that they are unique and live their lives in this

spirit. To us they may seem uncooperative, egotistical, and fatally flawed by a sense of

overweening pride, but we should remember that our world on the other hand produces many

persons flawed by having no sense of their own value or personal identity. We and the early Greek

heroes are a world apart, actually polar opposites, and this often makes it difficult for us to see

what they were doing or from what historical level they were emerging. In the following pages we

can examine some of the more important Greek heroes in the matrix of their myth-histories, not

viewing the sagas literarily and humanistically in relation to our world, but as documentary

statements coming from a remote past.

In Homer's epic, Achilles has grandeur of manner, he is complete and entire in his absolute

confidence, he has a great-spirit (as the Greek term 'megalo-psychos implies), but he is essentially

a lone warrior who is not able to work closely with a well knit military campaign. As every

student reading Homer immediately notices, Achilles does not play the game right; when crossed,

he withdraws and lets his fellows fend for themselves, he is (in our terms) a poor sport, sulky and

impossibly ego-centric. If everyone in the Greek army behaved like Achilles there would have

been no victory over Troy, let alone even the possibility of a campaign. Achilles stands as the

representative of an earlier genre of hero, who works singlehandedly against great odds, finally

achieving hero-status by his superb and concentrated fighting skill.

Greek mythology is populated by many such heroes, Heracles is another great example, better

documented than Achilles in the wide range of his endeavors. These "left-over heroes" from an

earlier stage of history still dominate the Greek idea of excellence, but they do not fit into the new

social world forming after the deterioration of the Minoan-Mycenean civilization. In that new

world the clever man wins out, he is often unadmirable in the eyes of later generations, he has like

Odysseus "seen many cities, and known the minds of men", he is a socially aware operator who

will lead toward the world which Greece was about to forge. In Homer's story about the campaign

at Troy, Achilles is a throwback to a state of human existence which had probably become extinct

a thousand years before. For that reason he is tragic in spirit, since he is condemned to early death

not by his mother's incomplete immersion in holy water, but by the steady development of a new

kind of society.

The story about Achilles' heel is odd, certainly more is involved than the mother dipping him in

protecting waters by the heel. In the tradition of the Japanese Judo Revival Points, massaging the

heel is performed to revive tired legs, perhaps we had here a similar process, which was

misunderstood by people who had no idea of its meaning.

But even the personal nature of Achilles is unclear to he. In Homer's war narrative Achilles is

fierce and devoted to warfare like a samurai, yet he is said to have been as being disguised as a

girl by his mother to avoid the Trojan war. We must remember his gentle affection and human

connection with Patroclos, which probably had homosexual overtones, as Bayle had already

suggested in l702. in his Dictionaire Biographique et Critique. While sulking in his tent after his

argument with Agamemnon, he plays music on the lyre, which recalls the uses of the samurai who

not only fought to perfection but also painted and composed song and poetry. A brief look at the

history of the l7th century samurai Miyamoto Mushashi arranges the possibilities of a warrior's

life: painting, poetry, calligraphy, design, sculpture, as well as the long list of the victims of his

sword and mind. The range of the warrior tradition was no longer clear in Homer's time, he gives

us only the outlines of Achilles, and none of the inner details about the kind of mind which directs

the body to the highest levels, whether of fighting, or any other human activity. But even so

enough of the Greek samurai comes through to gives us a chilling dash of admiration.

The complete warrior knows that he must expect death at every moment (without expecting or

thinking about it), he must have no regard for himself or any other person, and he will always

seem cold, passionless and faceless to the world. In this removal from connections lies one of the

sources of his power; the other lies in eternal practice with the body, the weapon and with the

mind. Only when Achilles forgets this rule of no-caring-ness, as he return to the fight to avenge

his one friend Patroclos whom he does really love, does he become vincible.

Hector, his opposite in the Trojan ranks, and also his opposite in the way he is cast in life, is warm,

caring, loving, even tolerant of an idiotic dandyish Alexandros, deeply understanding of Helen,

and dear to his family. Having all the human virtues which we think good, he has a weight of

responsibilities which unfit him for the role of a first-class warrior, and it is clear that he must die

in battle. But caring or not caring seems to make little difference, neither hero is fated to have a

long life and die a patriarch at home. Tragedy surrounds the Homeric hero, who is tragic because

he is obsolescent in social terms.

The samurai felt this same sadness when they were formally disbanded in the l7th century, their

days had run out and there was no longer a place for them in the world they had known.In the

story of Ajax, we trace a superior and proven warrior disintegrating into suicidal schizophrenia

over the issue of the inheritance of the famous arms of Achilles. The administrators of the society

refuse his claim, but since he has no understanding of the society's priorities or of the way they

work, giving now this and holding back that for the good of the many perhaps, his sense of self

falls apart. Since there is no other identity than this "sense of self", which is the sole premise on

which Ajax operates, when that identity is violated, there is no other course than death.

The schizophrenia suffered by Ajax when he was denied the arms of Achilles, indicates a general

social appreciation of arms as technology at a time when the availability of such equipment was

scarce. We know that bronze was being cast in the Near East and in parts of Europe before the

fourth millennium B.C., and that iron technology was being developed, if rare, a thousand years

later. Hence this story must go back to a much earlier period, perhaps the first few generations

after the development of usable metal arms. By 700 B.C. arms were sufficiently cheap for the

poet-soldier Archilochos to joke about scrapping a nice new shield in his hasty retreat, something

which Ajax would never have considered.

Ajax slaughtered a flock of sheep, thinking them his enemies, then took his own life. The presence

of sheep may suggest a date for this episode, and either a locale in inner Asia Minor whence sheep

seem to have spread, or a place to which sheep were already being imported. Jason's Argonautic

expedition after the "Golden Fleece" is discussed elsewhere as a first effort to bring sheep for

breeding from the Eastern Euxine area to Greece, and should be of a date somewhat earlier than

Ajax's period.Heracles is the fullest source for information about the man of strength and courage

who antedates regularized socialization, his "Labors" are important marks for man's future

development, but they are outlined as actions which one man performs alone. Only in the

friendship with his apprentice Hylas, who will be discussed later, does he work with another man,

and even then his friend is doomed to death and early disappearance from the story.

Heracles does not deal with other men, he cannot even understand the strategem by which his wife

Deianeira uses a poisoned cloak to burn and destroy him. Even that poison came from the blood of

a Centaur, a man-horse warrior of another age which Heracles still could not understand. Heracles

had tamed the wild horses, but he had not foreseen the social 'poison' that horse-warriors could

bring to to the world, and even finally to him. Heracles is a central figure for Euhemeristic

interpretation. Described and portrayed in art as a massive man with a growth of beard, wearing a

lion's or other animal's skin, and carrying a club as his regular weapon, his date must be pushed

back to a pre-Minoan-Mycenean culture, of the type which existed from Greece northwards into

central Europe at an early period. Perhaps the views of Rhys Carpenter about desiccation of the

Aegean area, and subsequent flight of the Hellenes into the better- watered northlands, may

contain some truth. Were this view eventually found workable, then Heracles would represent the

physical and social type of barbarized Hellene whose people had spent some three centuries in the

wooded north as they reverted to neolithic culture, finally returning when the drought was over, to

their homeland in Greece in the ninth century B.C. with the physical characteristics of a

Heracles-type. Attractive as this view seems, in order to be accepted, it will have to be be

supported by carbon dating of successive campfires going north and finally returning to Greece.

Confirmation of this view must wait until the Balkan countries are in a position to undertake

research of this sort.

In literary texts Heracles is described as going through various stages of insanity, Euripedes' extant

and very odd play, the Heracles Mad, explores his insane state of mind. But recall that erratic

social behavior, especially in the case of an adoptive neolithic with three centuries of forest living

behind him, may be at the root of this "dislocation". Behavior which would have been well suited

to survival in the forests, would be out of place in a land which was again increasing in population

and developing fast-growing social patterns. The Labors of Heracles (Gr. ' athloi' or 'ponoi') are

listed as an even dozen. This number may have significance, since dozen-counting was practiced

in the Near East in some areas. We can assume that the final listing of Heracles' Labors was late,

since it matches Homer's listing of his books by the dozen, twenty four in all in each epic, but we

cannot be sure at what period of redaction this ennumeration took place. Babylonian counting was

sexagesimal, since sixty is conveniently the common divisor for twelves, tens, and threehundred

and sixty, all of which have strangely persisted to the present day as minutes, seconds, hours, and

degrees, but it difficult to state exactly when these numbers entered into the Greek tradition.

The Greeks' inability to deal with numbers effectively, since they never developed a good cipher

system, makes us suspect that any odd numbers that they used must have been borrowed from

Near Eastern sources, probably along with the Phoenician letters which appeared somewhere in

the ninth century. Looking at the "Labors" in the traditional order, we find a wide range of feats

which must obviously have been performed by many men over a long period of time. Heracles'

name has an etymological connection with Hera, the meaning of which is not clear; perhaps his

name ('Hera' + 'cleos' "fame") may have violated some ancient sacral copyright. However Hera is

his enemy throughout life, ostensibly because of his birth from Alkmene by Zeus. She persecutes

him with serpents when he is an infant, with murderous madness when he is adult, perhaps as

some mark of an ancient cult-rivalry which we are not aware of.

l) The story of the Nemean Lion,which Heracles strangles and then rips open with its own claws in

order to remove the skin from the body, must be a very early myth. Learning to make flaked

flintstone implements, man developed the kind of edged tool necessary to open up an animal

which he had clubbed to death with a stick or a broken off antelope-bone shillelagh.

Anthropologists have discovered that the only animal a man can rip open for food after killing it is

a rabbit, everything bigger resists the action of his nails, fingers and teeth. The man who sees that

the cat's claws are first-rate slitters must be living in early old stone age culture, since later flaked

and sharpened stone gives him his own tools, with an excellent cutting edge. Middens and

stoneworking fields show that slitting stones were common and used everywhere in Europe in

neolithic times.

2) The next encounter was with the Hydra, a watersnake equipped with numerous heads. We may

be dealing with a story describing the octopus, which confuses legs and heads in the whirl of

activity. But soon a crab appears to aid the Hydra against Heracles, his legs are of course

genetically coded for regrowth upon loss, and this feature enters the story. Fighting the hydra and

the crab, which is probably not a freshwater animal, Heracles must be in a very wet, perhaps

brackish area, one suspects a location somewhere in the Euphrates valley near the extensive

marshlands where the river empties into the sea. Clearing wetlands of any dangerous animals (the

exact kind is less important than their presence in the face of increasing population and land-use),

would be an early activity, perhaps derived from the experience of NearEastern history at the time

time when the Euphrates valley was being drained and productively irrigated. Placing the story in

Greece loses the point, since very few Greek locations were suitable for such water-life, and those

were so small in area that they could be ignored without loss. The fifth millennium B.C. might be

a good rough date for this sort of feat, presumably with an eastern locale.

3)The Erymanthian Boar might be a a denizen of deep forest and possibly middling highlands,

either in Asia Minor or Europe. Driving the boar into the snow where its short legs sink it in deep

snowdrifts, Heracles may be reflecting the Carpenter-theory sojourn in Hungary or Southern

Germany, where such a scene could easily have occurred. Were this possible, it would point to a

wide geographical distribution of Heraclean mythologizing, which can be interpreted as the

conflation of many "Heracles-type" adventures which are not necessarily referable to one single

actor. At the present time large and aggressive boars are still found in the marshes of the lower

Euphrates valley, and the story could have its origin there; but the detail of driving it into deep

snow points to a second-level development in the Central European hill country.

4) The Stag of Ceryneia seems to fall into the same class as the boar, it would be the inhabitant of

densely forested areas, again suggesting a northern locale. One difficulty, of course, is that we do

not know exactly which animals inhabited which forests at remote periods, although again further

scientific study of plant pollens and animal bones in identifiable age-levels could be of critical use

in such arguments. We can consider the possibilities now, but for proof we will need more detailed

study.

5) The Birds of Lake Stymphalos (said to be in Arcadia which is centrally located in the

Peleponnese) are harder to understand. They were supposed to be man-eating birds, but we know

now that the largest avian predators have no ability to carry off anything larger than a small lamb,

and this with some difficulty. Perhaps the birds were vultures feeding on dead flesh and

occasionally eating dead human remains, so that hunters chancing on such a scene would naturally

assume the birds had killed the men. Annual migration patterns of birds are quite stable in time,

we should consider whether these birds were storks, cranes or some other large birds migrating

from European summer grounds to North Africa for winter, as they still do. Heracles would have

had no purpose in killing these birds, but if we could identify the migratory patterns, we should be

able to place the scene of his action fairly well. Raptor patterns of annual migration at the present

time go in two paths: Some cross the Mediterranean at Gibraltar, others go clear around the

eastern end of the water. Apparently there is a strong aversion to flying over open stretches of sea,

either from fear, or because of loss of typical landmarks which are their migratory "map". We

would seem to be dealing in this myth with the eastern migratory flight, which would place the

scene in which Heracles is involved either at the Bosporos, or possibly east of the Euxine Sea,

perhaps in Colchis. Again, only ornithological experts with historical background can contribute

useful material here.

6) The episode of the cleaning of the Augean Stables, on the other hand, has clear relevance to an

important stage of developing civilization. The vast herds of King Augeas (said to be of Elis in

Greece), had accumulated such piles of manure, that their disposal presented an insurmountable

problem. The story tells that Heracles was requested to clear out the stables in one day, but the

time factor may be merely a reflection of the fact, that when Heracles diverted a portion of a river

through the stables, the manure went out quickly, perhaps in one day, in a fast-moving, liquid

slurry. Water is still one of the practical ways of cleaning barn manure, in a pre-machinery time it

would have seemed the magic barn cleaning machine.The story implies that animal breeding was

so far advanced that disposal of manure was beginning to be a problem. Herds of hundreds of

horses and cows would make people wonder where the manure might go, but herds of thousands

would make disposal a real problem. Manure fulfils a special role in farming, since the

complicated blends of enzymes which are required to break down grasses in ruminants' multifold

stomachs, when spread on the fields make possible a more intensive and productive farming

enterprise than can be envisioned without animal excrement. The double cycle which involves

animal breeding along with plant cultivation was certainly the foundation of the prosperity and

larger population potential of the Mesopotamian valley area, and the myth of Heracles and the

stables embraces both aspects, since the river conveniently floods the manure out of the barns and

right onto the fields. We may assume that we are dealing with a complicated and well-organized

flood-cleansing system, which used animal manure and plant culture to the fullest potential.

Strangely, the concoctor of this myth saw only the cleaning of the stables as worthy of comment,

he makes no mention of where the river waters went, or what use they finally served. This is a

good example of a Greek myth which contains procedures far more sophisticated than the story

teller knows.

9) Heracles expedition against the Amazons is located in the same mythic plane as his struggles

against various monsters, which have led some scholars to believe that the Amazons are as

fictitious as the other beasts. Since we have found grains of truth in many of the other labors, we

will approach the Amazons as reality to start with. First, they are associated with the north shore

of the Black or Euxine Sea, where we know about Greek activity from an early period. Achilles,

Theseus, Priam and others have already been reaching into the Euxine Basin, and the conflicts

which arose from eastward expansion must have been the original cause of the trouble at Troy.

It is possible that western peoples meeting primitive tribes on the southern plains of Russia, where

warlike behavior may have been coupled with long hair and what seemed to the Greeks traditional

female dress, could effect a sexual mis-identification. Killing one of these barbarians, the victor

would soon see that there were no breasts, but rather than yield to fact, he could fabricate the story

that they burned their breasts off for easier fighting, or if they were right-handed archers, they

removed only the right breast. But the difference between male and female genitals is clear,

therefore his seems an obtuse interpretation.

One of the most basic human identifications is the discrimination between the sexes, yet it must be

remembered that even in our time clever transvestites can fool the observant eye. On the other

hand, if we assume the existence of a thorough-going matriarchy, coupled with female

aggressiveness extended even to warfare, then patriarchal Western people would surely see this as

a totally different and threatening type of social organization, to be wiped out not because these

women were inherently dangerous, but because they represented such a basically different social

structure. The Bohemian queen Vlasta in the 8th c. A.D. waged a fully staged war against the King,

in the l6th century Spanish explorers found women warriors in Brazil, which is why they named

the central river the Amazon. Women in the l9th century were active warriors in Dahomey in

Africa, and women have been effective soldiers in the modern army of Israel.

Since Womens' Lib. in the United States, the levels of female violence have risen gradually,

including several murders of seeming rapists by karate-skilled females. Our myths of the naturally

gentle sex have probably been generated by the domination which men have been able to exercise

over women for millennia, although hormonal factors must also be at work. We are probably as

much in the dark in such matters of sexual identification as was Heracles when he faced his first

Amazonic Lady of Scythia. But the interesting point to make in closing, is that despite the long

and even history of "pacification" of women in the Western world, the story of Heracles and the

Amazons documents, although in puzzling manner, the possible existence of wild and untamed

warrior women at an early, pre-Hellenic date.

Perhaps the real difference between Hellene and Amazon lies in the distinction between tame, that

is socialized being and one who is "wild". Anyone who has raised children,or even dogs, will

recognize that in the infant animal there are traits of a "wild phenomenon", which can be subdued

by touching with the hands, petting, cajoling and finally threatening. Children and most

domesticated animals respond well to this pacification if it is done in the period of early

development, and wild animals can be dealt with in the same manner if the treatment is started

early enough, although the results are never completely assured. Certain types of human criminal

"psychopaths" seem not to have been influenced by these processes; in wartime men are "taught"

to unlearn their peaceful training, which may not be recoverable later in the normal social world.

Perhaps the Amazons represent nothing more than the way "wild" humans at a different level of

development would appear to highly socialized Greek men.

l0) The Cattle of the Sun God, which were stolen by a monster named Geryon who fled with them

to the remote western part of the Mediterranean Basin, refers to a western movement of

colonization, which threatened the beef-industry of the East, much as the Australian sheep market

has threatened the European and American lamb and mutton packers. If this is the meaning of this

story, we must tie it to the thrust of Western expansion, which we generally date relatively late in

the second millennium B.C. But on the other hand there are Indic myths of the cattle of the sun

being stolen, but these are always sheep whose fleecy coats are identified with the rainclouds

which must be returned if the country is to prosper agriculturally. The transfer from sheep to oxen

is strange, but after the meaning of sheep (as rainclouds) vanished, the name of any prevalent

herd-animal could easily be substituted. An interesting parallel is found in the myth of Helios the

Sun God, the son of Hyperion and Thea, who each day rides his chariot across heaven and in the

night is transported back again in a golden bowl.

Homer notes in Odyssey Book 11 that the sun-god has cattle and sheep in Trinacria, later renamed

Sicily, which would certainly be a western frontier for the early Greek colonists. If archaeologists

find many sheep bones and few ox bones in the western fringes of civilization, we can assume that

the original meaning of the Vedic myth lay behind the Greek story, and that the desiccation which

Rhys Carpenter has posited for the second half of the second millennium B.C. was the driving idea

behind this myth: Someone had to go and get the rain back. If Heracles is one of the "Dorians"

who went north into Hungary to escape the drought, and his people came back later with rainfall

(in Herodotos' words) as "the return of the descendants of Heracles", then he would be a natural

person about whom to center a story telling why the rainclouds went to the west. If climatologists

find that the rainfall in Spain was plentiful through all this period, then Heracles may be assumed

to be a "rainmaker". Identification of his name with the Pillars of Hercules shows that he was

thought of as going all the way to the Atlantic Ocean in his search.

ll) The Apples of the Hesperides are fruit which Heracles found while on the previous adventure in

the far West. If pollen indicating the presence of Seville Oranges or some similar fruit can be

identified for this period, then we would have to look no further in the unravelling of this myth. In

any case some exotic fruit seems to be involved, and it is either brought to Greece before it rots by

fast shipping, or the plant has been successfully transplanted.

l2) In the final Labor, Heracles descends to the underworld to capture the three headed dog

Cerberus; or in the Homeric variant of the tale, he tries to conquer Hades or Death himself This

story is analogous to the less aggressive descent of Odysseus into the underworld, and furthermore

to the Babylonian epic of Gilgamesh, which in its earlier Babylonian fragments points to a date

before the second millennium B.C. (A full, if old summary of the provenance and detailed

contents of the Gilgamesh material is to be found in the Encyclopedia Britannica, 11th ed.

s.v.Gilgamesh, by the American Semiticist Morris Jastrow.) Here again what seems to be typically

Greek, is clearly connected with the thought and history of a much earlier period in the NearEast.

The fact that the Greek stories are so well known known to us all, while the NearEastern stories

are fragmentary and obscure, makes it difficult see exactly what sections Greek mythology

derived from the myth-histories of the eastern peoples.

A detailed inquiry into the parallels which exist between the Greek and Sumerian stories is beyond

the scope of this chapter; the important thing to note is the existence of clearly parallel storylines,

the Greek myth being the derivative version. All in all, the stories associated with the name of

Heracles contain materials for the identification of a new type of semi-social man who is quite

different from his late neolithic ancestors. He performs heroic deeds which pave the way for the

requirements of civilizing man, opening up large tracts of land for profitable use. But he works

alone, he is a singular figure and only for a short time takes on the apprentice Hylas, who soon

disappears. The broad scope of these stories, as well as their regular development in later Greek

mythologizing culture, places them at the center of any serious search for fact in myth.

A hero of quite different dimensions is the master archer Philoctetes. He has one special ability, he

wields the bow that never misses its mark, and his ability with this remarkable weapon, which

would make him a supreme hunter in a age which lived by hunting, makes him the object of illwill

and hostility in an age which devotes itself to warfare. Needing his bow, but being unwilling to

accept the pure and direct mind of the master hunter who owns it, the Greek leaders are unable to

give Philoctetes recognition for his talents. On the other hand he cannot recognize their the

legitimacy of their military purpose, which is foreign to the world from which his skills in archery

emerged.

Isolation and tragedy are his reward in the original story, although Sophocles characteristically

gives his play an ending worthy of the social aspirations of the Athenian 5th century, and has him

willingly return to the world of men and the Trojan War.Heracles gave his bow and arrows to

Poias on his death, they passed in turn to Poias' son Philoctetes who was one of the Greek warriors

who sailed against Troy. On the way there, he was bitten in the foot by a snake, the wound festered,

he screamed out in such pain that the superstitious Greeks shanghaied him on Lemnos where he

lived for years, sick and lonely, living by the bow which could never miss its mark. Later it was

revealed at Troy that the city could be taken only with the bow of Heracles, now the Greeks

realized they had to reclaim Philoctetes, or kill him and get his bow, in order to conclude the long

and costly war. But the story has other dimensions. The man who possesses and wields the

unerring bow, is a hunting virtuoso in a primitive hunting world. Philoctetes uses the bow to hunt

and provide his food for all those years at Lemnos, this is probably the original scope of the

unerring-hunter tale. But it is now injected as an episode in the life of a military archer, which is

what the Greeks expect Philoctetes to become. For some reason, circumstantially ascribed to his

bad foot, Philoctetes cannot be drawn into the military expedition against Troy, his excellence

remains entirely with his weapon and never involves social action in an organized army.

When it is revealed that the Greeks cannot win the war without the weapon, they send someone

(Odysseus is just the man for such a job) to get it done at any cost. Sophocles creates a

sophisticated story of honor and duty, finalized with an apocalyptic vision of the hero's patron

"saint" as Heracles gives him instructions, and Philoctetes returns voluntarily with the bow,

behaving as a as a good Greek soldier should. One suspects that the original of the story was less

pleasing, that the soldiers killed the man and thus got the bow, thinking that they too would be

able to use it unerringly. (The missing sequel would have been the efforts of Greek archers to bend

the bow which only Philoctetes can use, in the manner of the story of Robin Hood's bow, but in a

country not populated by a youth skilled in archery, such a sequence would pass unnoticed.)

Archery in fact was more an Eastern than a Greek skill. To become a great archer is a life's work,

the archery tradition in Japan makes this clear, and the remarkable account by Herrigel on the

difficulties of learning bowmanship shows that only a dedicated and talented man, with more than

a little monomania, can become a great archer. There was just such a Greek myth about

Philoctetes, but it focused on his weapon rather than his skill. But when an effort is made to "hire"

Philoctetes into the army, to use his proven skills at archery for a common goal, and no longer for

the private and personal purpose that the hunter and archer have developed, it is doomed to failure.

Philoctetes has powers that cannot be used socially, and for this reason they had to be rid of him.

Needing the bow, they went back to him and probably murdered him; in Sophocles Fifth Century

version an arrangement is made by which Philoctetes goes back to men and the world of Troy, just

as the Elizabethan Prospero must also finally return to the world of men.

Early men of great power, inventors of new techniques and devices, as characters on the stage of

man's early dramatization, seem to have great difficulty in accepting concerted social interaction.

Heracles is the model for a man of great effectiveness, so long as he works by himself or with one

companion, and Philoctetes inherits along with the bow this same social disability. Achilles'

grandeur lies in the fact that he works alone and only for his own honor, this is his heroic mark

and in social terms this is his fatal flaw. The earliest levels of Greek myth point again and again to

a period before the regularized socialization of Man begins, and the tragedy of many of these early

figures, especially in their death scenes, lies in their unwillingness or inability to involve

themselves in social behavior. Note that the Classical Japanese samurai, who have many of the

same traits of independence and individuality,were legally dispersed as a warrior class in the

sixteenth century as the country progressed into a more unified, federally controlled state. They

converted themselves quickly into leaders in the arts and crafts, and finally socialize under an

entirely different professional guise. The Greek individual heroes, like Achilles, Heracles and

Philoctetes, eventually disappear from the scene, and are replaced by willing social partners in the

mould of the wily, venal Odysseus.

It seems that in the course of the development of a civilization, there comes a time when powerful

individualists are no longer needed, when society assumes that it can get the same impressive

results from the group-effort of many less gifted persons. The ants experimented with this problem

three hundred million years ago, they developed societal goals so far as to completely eliminate

individuality and even individual sexuality. They seem to have been correct for themselves in

evolutionary terms, but whether this is also true for our breed remains to be seen.

A Greek wit remarked that there is a curious contradiction in the use of the Greek word 'bios'

(which means both "bow" and also as a separate homonym, "life"), since the bow is the instrument

which represents and at the same time destroys life. The weapon is a great advantage to

humankind, but at the same time a deadly threat to life, situations of this kind are familiar to men

of the twentieth century, the atomic energy which our society has pioneered can offer the greatest

benefit to mankind, since it produces energy without the cumulative combustive pollution of wood,

coal or oil, yet it presents the greatest possible threat to the survival of mankind. This is our

modern "bow". It is worth noting that Robert Oppenheimer, the one member of the original

pioneering group at Los Alamos who had serious doubts about the use and misuse of atomic

energy, was singled out during the infamous MacCarthy period as "suspect", not on the count of a

snakebitten foot, but because he may have carried a Communist card many years before. He was

shanghaied, as was Philoctetes, not to Lemnos but to the Institute for Advanced Studies at

Princeton, where certain political powers felt he would be rendered harmless. He fulfilled

administrative duties there to consume his time, and died many years later, unheard and largely

unknown. The society took his weapon away from him, they used it for their purposes, and they

silenced this one serious opponent of unbridled use of atomic energy by an act of ostracism rather

than by death. Some situations which confront men do not change a great deal through the

centuries, apparently the critical and lethal weapon is still usable without the consent or advice of

its owner. We have progressed greatly in the size and destructiveness of the weaponry, but not in

our understanding of its control or proper use.

A striking example of the opposition of one individual to coercive social commands is the story of

Antigone. In Sophocles' version, from which most of our portrayal of Antigone's character comes,

the issue is between what one owes the "state", represented by Creon the king, as against what one

owes the older structures of clan and family religion. There is more to the story than this skeletal

outline, but the basic problem is simple and central: Does the state have the final say in this new

world of social imperatives, or are there moral and personal roots which go back into the ancestral

past? The drama of Antigone in its most elemental form, demonstrates the inability of a woman

who is schooled in the traditional values inherited from her past, to comprehend, let alone obey,

the orders which society presses on her through the agency of the King.

This is only part of the gist of Sophocles' drama, but it is probably an original part of the ancient

myth, since this same inability to socialize is found in almost all the genuinely early hero-myths.

The insistence of the Greeks in the 5th c. B.C. on the absolute value of social behavior may well

be a last act in the difficult drama of the earlier Greek people in accepting any form of social

enforcement. Even in the Greeks of the later Classical Period there remains a wild streak of

intransigent individuality, which makes the process of democratic cooperation always difficult and

often impossible. Each of the mythic figures which we have been examining has a striking and

distinguished personal history, each reveals details which stem from centuries or possibly

millennia of advancing human experience in the eastern Mediterranean world. But all show the

same inability or at least unwillingness to act in social concert with others, their minds are entirely

oriented to what they are doing and not what the others want. Hence they fail in what socialized

and civilized men and women consider the core of civilized behavior. Yet there is something grand

and independent which we recognize in their lives, since individuality is still prized among us,

especially as vast social forces seem about to swallow up our remaining personal identities.

The real problem is certainly not a conflict between individual and social action as such, but an

understanding of what each can do especially well in its own sphere. In our day when committees

and think-tanks tend to be the socially approved modes of generating new ideas, we might well

remember the effectiveness of thought and action which individuals have shown in the past. It is

usually when the force of a social experiment is new, or on the other hand when times are

especially desperate, that society tends to force one pattern onto us as mandatory. This is exactly

what was happening in the first two millennia before Christ, and it is the inability of some ancient

men of great force and ability to adjust to the new social ways that is so insistently recorded in the

curious chronicles of Greek mythology.

As times went on, the Romans started to "create" myths of their own, to suit their own social

needs. These are largely based on the form and general style of the Greek mythologists, with

whom the Romans were well acquainted. If they could not read the large full-scale version of

Greek mythology in the Greek of Apollonius they could read an abridged version more

conveniently in the Latin of Julius Hyginus. The myths which they constructed should be

considered "myths-of-the-second-level", or pseudo-myths. As examples of this phenomenon, one

can note these: Aeneas is the sort of fabrication which every people develops for its own honor. It

seems possible that the whole Aeneas myth was generated out of the archaic Latin word

"trossulus" a cavalryman of the early period. The word has no known affinities and may be of

Etruscan origin, but since "trossulus" would be interpreted by any Roman as a "little Trojan,

descendant of Troy", or even more specifically "descendant of Tros (the fourth generation in the

formal family tree of Troy, viz. Zeus, Dardanus, Erichthonius, and Tros), this would provide a

convenient point of departure for a noble legend following the influx of Greek literature into

Rome in the third century B.C. This view is by no means accepted by Classical scholars, however

the fabrication of quasi-archaic figures is well known to Americans, who have acculturated a

largely reshaped Santa Claus, a wholly new Paul Bunyan whose cycle dates only from the l920's,

as well as a long series of Western style gunfighters who have only the slimmest connections with

history.

There is a certain advantage in fabricating one's own national heroes, since they have an uncanny

way of fitting the society perfectly. The one Roman who fits the pattern of the Greek hero tales is

Romulus, and then only in one single matter, the confrontation of the pasturing and the farming

ways of life. When Romulus built a wall for his city, Remus jumped over it with a sneer, to be

immediately killed by his brother, who was not held guilty. We have here in a late form the old

confrontation of the settling field-tender, who marks off land for cultivation, as against the

free-roaming pasturer of flocks. The story is identical with that of Cain and Abel, and it is a

foregone conclusion that the herdsman must die, which signifies that civilization must be allowed

to go forward. Many of the young Greek hunters of myth faced death for similar reasons, since as

hunters they crossed cultivated land (probably unbeknownst to themselves) and thus were a threat

to agriculture.

For a very brief period in the middle of the l9th century the same confrontation was found among

the Western settlers in the United States; the cattlemen detested the dirt farmers, and exactly the

same kind of bloody antagonism prevailed as the earlier peoples had known. The cattlemen

received a secure place in the society only because of the useful transportability of live meat by

the newly developed rail lines to distant markets in the East, as well as increasing American

consumption of meat, while agriculture proceeded at its own pace. A double-headed market can

ensure compatibility between these two opposed groups. If we can reliably date Romulus as 8th c.

B.C., then Cain and Abel would fall into a proper place some centuries earlier; this tells us

something about the date of the advent of serious cultivation of the land for crops in the

Mediterranean area.

At an early date there was a separate Latin divinity named Saturnus, "he who sows (seed for

grain)" from the verb ''serere, satus'. Roman tradition states, in a virtually Euhemeristic tone, that

he was an early king at Rome who introduced agriculture and was hence elevated to deity-status.

(The later identification with Cronos is merely a part of the Greco-Roman equivalent

identification of deities, a process which often obscures important, original details.) Here again we

have a newly fabricated "doer-deity", with real social meaning for his society; he does not

however have a historical pedigree going back into the time of the earlier cultures from which the

Roman benefited. The socialization of man does not take place in a moment or in a thousand years.

Despite the difficulties of early heroes in adapting to group behavior, the process of socialization

goes on unrelentingly, since larger frameworks of social action are needed for larger populations

and their daily support.

A transitional stage between the hero as isolated individual and the new hero as part of a societal

effort, is to be seen in a curious inter-stage, which serves as bridge between the two patterns. We

find as adjunct to lone hero, the hero-pair, consisting of the hero, a man of great power and

experience, and an apprentice and companion, usually a younger man who is clearly in a

subordinate position. This inter-stage marks the transition of the hero as individual to becoming

group-member, it is clearly transitional and short-lived as a social phenomenon. Achilles

relationship to Patroclos is typical of this kind of association. Patroclos is tent-mate, householding

assistant, and a general purpose companion, but when he dies wearing the master's ill-suited armor,

the full depth of Achilles' tragic feeling for him emerges. This is no mere apprentice to the trade, it

may be a relationship which contains seeds of love and even homosexuality. But paramount is the

fact that it is the kind of pair relationship which joins two unequals, as Aristotle will remark of a

class of friends at a later time in the Nichomachean Ethics. There is no competition for honor or

glory, so the two can be companions in a real sense, and useful to each other in dangerous

situations.

The origin of this uneven-pair system apparently goes back in history as far as the story of

Gilgamesh, whose friend and companion Eabani is fated to die, to the hero's great grief. Achilles

and Patroclos fulfill similar roles, and in the Greek cycles of myth there are many examples of

such relationships, including the popular story of the twins heroes Castor and Polydeukes. They

are nearly equal, Polydeukes however is immortal and Castor perishes; the story that Zeus gave

the mourning twins alternate days in Hades as a special favor may well be a later addition. At

Rome Castor is the more popular figure, and Pollux (Polydeuces) is clearly subordinate. The story

of Hylas fits into this hero-friend classification well. On the Argonautic expedition, Heracles took

along the young Hylas, who was sent to fetch water for the sailors when stranded temporarily off

the coast of Mysia (Asia Minor). The nymphs of the fountain at which he was drawing water fell

in love with him, and sucked him down into their world. Heracles was stricken with grief, and

only left the area when, at his behest, the natives instituted a ritual springtime sacrifice to Hylas,

who thus appears retrospectively in the light of a vegetative annual-cycle deity. Hylas fulfills the

basic conditions of companion to a hero: He is young, subservient, handsome, devoted, helpful,

and at the proper moment he dies, leaving the hero free to go on his road of achievement alone, as

was proper. This unequal but friendly working relationship between two men would seem to be

one of the primitive stages of social development. Not only do the two men work and fight beside

each other, but a sincere emotional atmosphere develops between them, so that the survivor

mourns long and hard for his lost friend.

Humans seem to find it much easier to develop working relationships in pairs than to participate in

the more complicated group activities, although the history of civilization in the West has relied on

group efforts in the main. Even today the ancient two-man team persists, we still find it

widespread in the modern world. Carpenters seem to get a great deal more work done if they have

a helper, cement finishers generally work in pairs, and in the army and police force the two man

"buddy system" is found useful. The single-combat, with one man fighting against another as

portrayed in Homeric scenes, is a much older structure, which seems to have intellectually

influenced a great deal of Greek military strategics in the historical period. By the time of the

developing tactics of the Punic Wars we have genuine group tactics on both sides, and the modern

concept of field-warfare is borne.

When Aristotle in the Nichomachean Ethics outlines friendship in its various forms, he speaks of

something which we often fail to identify, the friendship between unequals as contrasted to the

friendship between equals. The working relationships which we have been discussing are all