PPS Review consultation - Reach of the Act - Attorney

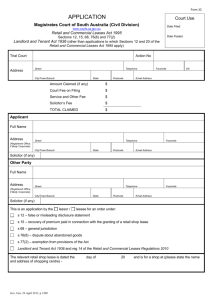

advertisement