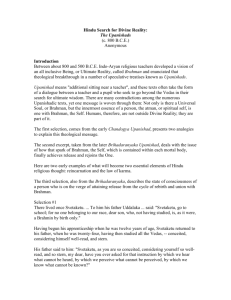

The Wisdom of the Upanishads

advertisement