PHILOSOPHY 100 (STOLZE)

advertisement

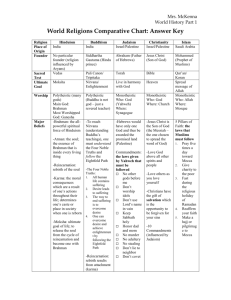

PHILOSOPHY 100 (STOLZE) Notes on Victoria Harrison, Eastern Philosophy: The Basics What is “Eastern” Philosophy? Harrison stresses the wide variety of philosophies in Asia and that there is no clear geographical border dividing “West” from “East.” Her emphasis is on the classical origins of Indian and Chinese philosophies. Philosophy as a Cross-Cultural Phenomenon Harrison argues that philosophies have “family resemblances” just like religions or games. There are some basic philosophical questions that occur across traditions: What is the self? What is the best way to live? Where do we come from? What happens when we die? Two Categories of Indian Sacred Texts Sruti: “revealed truths” Vedas Upanishads Smrti = “memory” Mahabharata Bhagavad Gita Ramayana Nine Indian Philosophical Perspectives (Darsanas) Astika = “affirmers” Nastika = “non-affirmers” Nyaya = the school of logic Carvaka = the school of Vaisesika = the school of materialist and hedonist atheists Jaina = the school originating from the teachings of Mahavira Buddhist = the school originating from the teachings of the Buddha atomism Samkhya = the school of dualistic discriminations Yoga = the school of classical yoga Mimamsa = the school of Vedic exegesis Vedanta = the school based on the “end of the Vedas” or the Upanishads) Ignorance In Indian philosophy ignorance “is a principal source of suffering because it gives rise to the attachments that lead to rebirth” (p. 25) Chapter Two: Reality In the history of Indian Philosophy there have existed three broad approaches to ontology (the philosophical study of what exists and what is ultimately or fundamentally real): • • • Pluralism (Nyaya/Vaisesika) = “reality is composed of an irreducible plurality of different kinds of object” Dualism (Samkhya/Yoga) = “reality is composed of two fundamentally different substances (matter and mind)” Monism (Advaita Vedanta) = “despite appearances to the contrary, at the most fundamental level only one thing is real” Śankara on Three Levels of Reality Śankara (788-820? CE) argued for nondualism = Layer 1: Absolute reality. Nirguna Brahman, Qualityless Brahman, Brahman/Ātman. Layer 2: Absolute reality seen through categories imposed by human thought. Saguna Brahman, Brahman with qualities. Creator and governor of the world and a personal god (Īśvara). Layer 3: Conventional reality. The material world, which includes “empirical selves.” Objections to Śankara By contrast, Rāmānuja (c. 1017-1137) defended only a qualified nondualism. He denied that Brahman could exist without qualities and argued that the qualities of Brahman are real in an absolute sense: “According to Rāmānuja, the absolutely real is a trinity of Brahman )as a personal God), a plurality of selves and the material world. These three together form a unity in which selves and the material world are portrayed as Brahman’s body. Brahman is the cause of the existence of selves and the material world. However, in creating them Brahman has transformed itself into these things in an absolute sense. Hence, Brahman has become dependent upon them. Each of these items is thought of as ultimately real in the sense that none can be reduced to the others. Nor could any of them exist without each of the others” (p. 61). Śankara vs. Rāmānuja on Liberation Liberation (moksa) for Śankara is achieved “when ātman realized that it was already united with qualityless Brahman” (pp. 61-62), whereas Rāmānuja argues that liberation “is a state of freedom from ignorance in which one is aware of one’s essential nature and of one’s relationship to Brahman” (p. 62). An underlying question: “Would you rather taste sugar or be sugar?” Chapter Three: Persons Self and World Self in the Upanishads Rebirth Karma Freedom Individuals No Abiding Self Dependent Co-Arising Liberation Krisha Teaches Arjuna about the Self (Ātman) “The self is not born nor does it ever die. Once it has been, this self will never cease to be born again. Unborn, eternal, continuing from the old, the self is not killed when the body is killed…. Just as one throws out old clothes and then takes on other, new ones; so the embodied self casts out old bodies as it gets other, new ones. Weapons do not cut the self, nor does fire burn it, nor do waters drench it, nor does wind dry it. The self is not to be pierced, nor burned, nor drenched, nor dried; it is eternal, all-pervading and fixed— unmoving from the beginning. The self is not readily seen; by sight or mind; it is said to be formless and unchanging; so, when you have known this, you should not mourn.” (Excerpted from The Bhagavad Gita 2.20, 22-25, translated by Laurie L. Patton [New York: Penguin Books, 2008, pp. 21-25.) The Three Jewels of Buddhism Buddha = a title not a personal name (“Awakened One”) especially Siddhartha Gautama (born c. 563 BCE in Lumbini, modern Nepal; died c. 483 BCE [or 411-400 BCE] in Kushinagar, modern Uttar Pradesh, India) Dharma = teaching about the way things are (from linguistic root dhr = “to fasten, support, or hold”) Sangha = the community of Buddhists, especially monks and nuns For an excellent overview of the Three Jewels (and the historical development of Buddhism), watch the BBC documentary Seven Wonders of the Buddhist World: www.youtube.com/watch?v=sQRCGBeXiow&feature=youtu.be Buddhist Ontology: Three Signs/Marks of Existence Anitya/Anicca = “impermanence” Anatman/Anatta = “not-self” Dukkha = “suffering, unsatisfactoriness, distress” The Four Noble Truths Dukkha The Cause of Dukkha (= “thirst,” craving, attachment, excessive desire) The Cessation of Dukkha (= Nirvana/Nibbana, “blowing out”) The Way leading to the Cessation of Dukkha (= The Noble Eightfold Path) The Noble Eightfold Path Wisdom Right Understanding Right Thought Right Speech Virtue Right Action Right Livelihood Meditation Right Effort Right Mindfulness Right Concentration The Buddha’s Theory of Anātman or “Not-Self” According to the Buddha, every human being is composed of physical and non-physical components that can be categorized as belonging to one of the following five categories or “aggregates”: • Body • Feelings • Perceptions • Mental Formations/Dispositions/Tendencies • Consciousness Key Confucian Concepts Confucius (551-479 BCE) = Latinized form of Kongzi = “Master Kong” Dao = way, or the Way (to understand the world or to lead a good life) De = virtue or ethical power to follow dao, to “do the best you can with what you have”—what you have is de Li = everyday rites or rituals that embody and express one’s virtue Ren = benevolence, humaneness, or human-heartedness, the chief Confucian virtue Junzi = a gentleman , an “exemplary,” or “exceptional” person—one who embodies and expresses ren to the highest degree Five Relationship and Virtues Relationship Father/son Husband/wife Older/younger brother Friend/friend Ruler/subject Virtue Filial piety Submission Brotherly respect Sincerity Loyalty NOTE: These relationships indicate an “expanding circle” of interactions with others and form the basis of society: showing concern for inferiors and respect for superiors. Moreover, the Confucian tradition considers the self to consist precisely of the complex structure of these overlapping relationships.