Crucial Conversations

advertisement

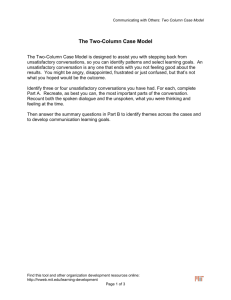

Crucial Conversations Excerpts from the book by Patterson, Grenny, McMillan and Switzler When we face crucial conversations, we can do one of three things: We can avoid them. We can face them and handle them poorly. We can face them and handle them well We are designed wrong -- when conversations turn from routine to crucial, we’re often in trouble because emotions don't prepare us to converse effectively. Your brain diverts blood from activities it deems nonessential to high-priority tasks such as hitting and running. We are under pressure; we are stumped; we act in self-defeating ways in our doped up, dumbed down state. The strategies we choose for dealing with our crucial conversations are perfectly designed to keep us from what we actually want. At the core of every successful conversation lies the free flow of relevant information. People openly and honestly express their opinions, share their feelings, and articulate their needs and theories. To put a label on this talent; it's called dialogue. When people feel comfortable speaking up, meaning flows freely and the shared pool of information can dramatically increase the ability to make better decisions. The pool of shared meaning is the birthplace of synergy. Start with heart. If you can't get yourself right, you'll have a hard time getting dialogue right. When conversations become crucial, you will be tempted to resort to the forms of communication that you've grown up with, that is a debate, silent treatment, manipulation, etc. First, focus on what you really want. What is your goal? Then refocus your brain. What do I really want for myself? What do I really want for others? What do I really want for the resulting relationship? There are common, but not all that healthy for dialogue, objectives including wanting to win, seeking revenge, and hoping to remain safe. Wanting to win is the dialogue killer that sits at the top of many of our lists. We start out with the goal of resolving a problem, but as soon as someone raises a red flag of inaccuracy or challenges or correct us, we switch purposes in a heartbeat. First we correct the facts and quibble over details and point out flaws in the other person's arguments. As they push back, it’s no longer about having dialogue and a free flow of relevant information, but a switch in our goal to winning. As our anger increases, sometimes we move from wanting to win to the point of wanting to harm the other person that is seeking revenge. We moved so far away from adding meaning to the pool of shared information, that dialogue stops Hoping to remain safe does not add to the pool of meaning as we can go to silence. Because were so uncomfortable with the immediate conflict, we accept the certainty of bad results to avoid the possibility of uncomfortable conversation. We choose (at least in our minds) peace over conflict. “They had lived together for so many years that they mistook their arguments for conversation.” Marjorie Kellogg If you spot real safety risks as they happen in conversation, you can step out of that conversation, build safety, and then find a way to dialogue about almost anything. What do you do when you don't feel like it's safe to share what's on your mind? The key is to step out of the content of the conversation. What will help establish safety, even when the topic is high risk, controversial, and emotional? The first step to building more safety is to understand which of the two conditions of safety is at risk as each requires a different solution. Suzanne L. Brunsting, Esq. :: 16 N. Goodman St. Suite 113 :: Rochester, NY 14607 :: (585) 244-4239 :: www.suebrunsting.com Mutual purpose Crucial conversations often go awry not because of the content of the conversation, but because others believe that the painful and pointed content means that you have a malicious intent. How can they feel safe when they believe you're out to do them harm? The first condition of safety is Mutual Purpose. Mutual purpose means that others perceive that we are working toward a common outcome in the conversation, that we care about their goals, interests and values. And vice versa. When purpose is at risk we end up in debate. Mutual purpose is not a technique. To succeed in crucial conversations, we must really care about the interests of others and not just our own. The purpose has to be truly mutual. Mutual Respect - As people perceive that others don't respect them, the conversation immediately becomes unsafe and dialogue comes to a screeching halt. Why? Because respect is like air. If you take it away, it's all people can think about. The instant people perceived disrespect in the conversation, the interaction is no longer about the original purpose -- it is now about defending dignity. Can you respect for crucial conversation purposes people you don't respect? Dialogue truly would be doomed if we had to share every objective or respect every element of another person's character before we could talk. We can, however, stay in dialogue by finding a way to honor and regard another person's basic humanity. In essence, feelings of disrespect often occur when we dwell on how others are different from ourselves. We can counteract these feelings by looking for ways we are similar. Without excusing behavior, we can try to sympathize or even empathize with them. Can we find a sense of kinship, a sense of mutuality between ourselves and even the thorniest of people? It is this sense of kinship and connection to others that motivates us to enter tough conversations and it eventually enables us to stay in dialogue with virtually anyone. Summary -- Make It Safe Step out and decide which condition of safety is at risk: 1. Mutual purpose -- to others believe you care about their goals in this conversation? Do they trust your motives? 2. Mutual respect -- to others believe you respect them? Apologize When Appropriate When you clearly violated respect, apologize. When others misunderstand either your purpose or your intent, use contrasting. Start with what you don't intend or mean and then explain what you do intend or mean. Get to Mutual Purpose When you are at cross purposes, use four skills to get back to mutual purpose: Commit to seek mutual purpose, recognize the purpose behind the strategy, invent a mutual purpose, brainstorm new strategies. “It's not how you play the game, it's how the game plays you.” How to stay in dialogue when you are angry, scared, or hurt. How many times have you heard someone say, “he made me so mad or she made me so mad”? Emotions don't just happen. They are not foisted upon you by others. No matter how comfortable it might make you feel by saying it, others don't make you mad. You make you mad you and only you create your emotions. Once you've created your emotions, you have only two options: you can act on them or be acted on by them. Suzanne L. Brunsting, Esq. :: 16 N. Goodman St. Suite 113 :: Rochester, NY 14607 :: (585) 244-4239 :: www.suebrunsting.com