Brave New World

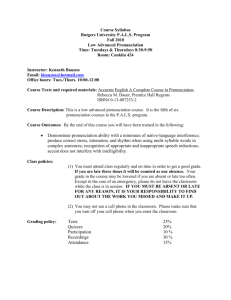

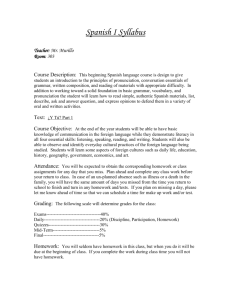

advertisement