Study Guide/Discussion: Swift`s Satire and Gulliver`s Travels

advertisement

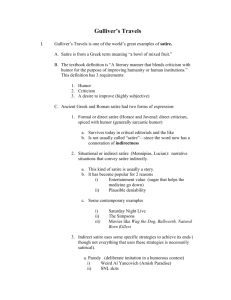

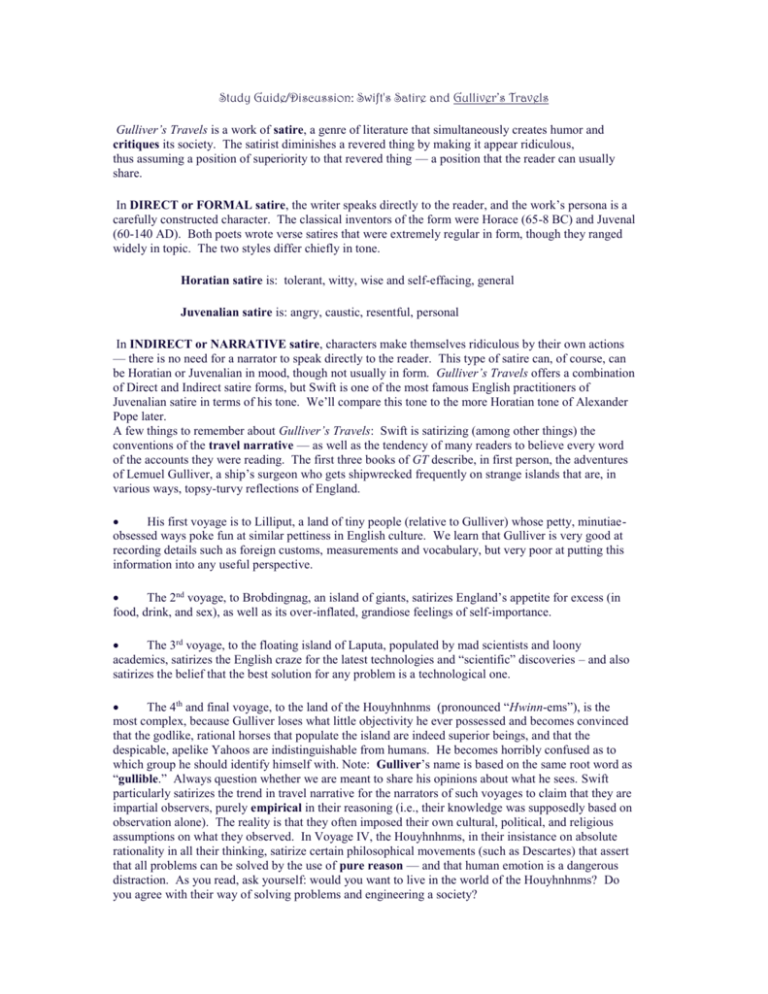

Study Guide/Discussion: Swift's Satire and Gulliver’s Travels Gulliver’s Travels is a work of satire, a genre of literature that simultaneously creates humor and critiques its society. The satirist diminishes a revered thing by making it appear ridiculous, thus assuming a position of superiority to that revered thing — a position that the reader can usually share. In DIRECT or FORMAL satire, the writer speaks directly to the reader, and the work’s persona is a carefully constructed character. The classical inventors of the form were Horace (65-8 BC) and Juvenal (60-140 AD). Both poets wrote verse satires that were extremely regular in form, though they ranged widely in topic. The two styles differ chiefly in tone. Horatian satire is: tolerant, witty, wise and self-effacing, general Juvenalian satire is: angry, caustic, resentful, personal In INDIRECT or NARRATIVE satire, characters make themselves ridiculous by their own actions — there is no need for a narrator to speak directly to the reader. This type of satire can, of course, can be Horatian or Juvenalian in mood, though not usually in form. Gulliver’s Travels offers a combination of Direct and Indirect satire forms, but Swift is one of the most famous English practitioners of Juvenalian satire in terms of his tone. We’ll compare this tone to the more Horatian tone of Alexander Pope later. A few things to remember about Gulliver’s Travels: Swift is satirizing (among other things) the conventions of the travel narrative — as well as the tendency of many readers to believe every word of the accounts they were reading. The first three books of GT describe, in first person, the adventures of Lemuel Gulliver, a ship’s surgeon who gets shipwrecked frequently on strange islands that are, in various ways, topsy-turvy reflections of England. His first voyage is to Lilliput, a land of tiny people (relative to Gulliver) whose petty, minutiaeobsessed ways poke fun at similar pettiness in English culture. We learn that Gulliver is very good at recording details such as foreign customs, measurements and vocabulary, but very poor at putting this information into any useful perspective. The 2nd voyage, to Brobdingnag, an island of giants, satirizes England’s appetite for excess (in food, drink, and sex), as well as its over-inflated, grandiose feelings of self-importance. The 3rd voyage, to the floating island of Laputa, populated by mad scientists and loony academics, satirizes the English craze for the latest technologies and “scientific” discoveries – and also satirizes the belief that the best solution for any problem is a technological one. The 4th and final voyage, to the land of the Houyhnhnms (pronounced “Hwinn-ems”), is the most complex, because Gulliver loses what little objectivity he ever possessed and becomes convinced that the godlike, rational horses that populate the island are indeed superior beings, and that the despicable, apelike Yahoos are indistinguishable from humans. He becomes horribly confused as to which group he should identify himself with. Note: Gulliver’s name is based on the same root word as “gullible.” Always question whether we are meant to share his opinions about what he sees. Swift particularly satirizes the trend in travel narrative for the narrators of such voyages to claim that they are impartial observers, purely empirical in their reasoning (i.e., their knowledge was supposedly based on observation alone). The reality is that they often imposed their own cultural, political, and religious assumptions on what they observed. In Voyage IV, the Houyhnhnms, in their insistance on absolute rationality in all their thinking, satirize certain philosophical movements (such as Descartes) that assert that all problems can be solved by the use of pure reason — and that human emotion is a dangerous distraction. As you read, ask yourself: would you want to live in the world of the Houyhnhnms? Do you agree with their way of solving problems and engineering a society?