Your Honour, An Appeal: Re-litigating `Accounting on Trial`

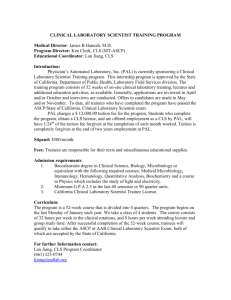

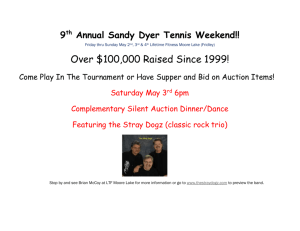

advertisement