批判法學理論

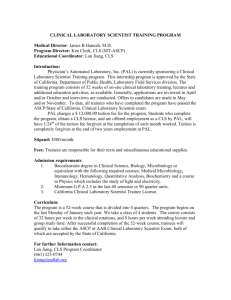

advertisement

批判法學 楊智傑 發展背景 • 「批判法學」(Critical Legal Studies)運動是美國自70 年代以來興起的一種法學運動,它承繼了美國「法律唯實 主義」(Legal Realism)對傳統法學中「形式主義」 (formalism)或「概念法學」(Begriffsjuriprudenz)的批判, 亦帶有些許「新馬克思主義」( Neo-Marxism)對自由主 義、資本主義批判的色彩。從80年代開始,CLS在美國 逐漸趨向多元發展,如「批判女性主義」(Critical Feminist)或「女性主義法律理論」(Feminist Legal Theory)、「批判種族法律理論」(Critical Race Theory)等 更是紛紛出爐,可謂百家爭鳴、百花齊放。 無法約束法官 • A first theme is that contrary to the common perception, legal materials (such as statutes and case law) do not completely determine the outcome of legal disputes, or, to put it differently, the law may well impose many significant constraints on the adjudicators in the form of substantive rules, but, in the final analysis, this may often not be enough to bind them to come to a particular decision in a given particular case. 法律即政治 • there is the idea that all "law is politics." This means that legal decisions are a form of political decision, but not that it is impossible to tell judicial and legislative acts apart. Rather, CLS have argued that while the form may differ, both are based around the construction and maintenance of a form of social space. The argument takes aim at the positivist idea that law and politics can be entirely separated from one another. A more nuanced view has emerged more recently. This rejects the reductivism of 'all law is politics' and instead asserts that the two disciplines are mutually interspersed. There is no 'pure' law or politics, but rather the two forms work together and constantly shift between the two linguistic registers. 法律乃保障有錢人 • the law tends to serve the interests of the wealthy and the powerful by protecting them against the demands of the poor and the subaltern (women, ethnic minorities, the working class, indigenous peoples, the disabled, homosexuals etc.) for greater justice. This claim is often coupled with the legal realist argument that what the law says it does and what it actually tends to do are two different things. Many laws claim to have the aim of protecting the interests of the poor and the subaltern. In reality, they often serve the interests of the power elites. This, however, does not have to be the case, claim the CLS scholars. There is nothing intrinsic to the idea of law that should make it into a vehicle of social injustice. It is just that the scale of the reform that needs to be undertaken to realize this objective is significantly greater than the mainstream legal discourse is ready to acknowledge. 法律自相矛盾 • CLS at times claims that legal materials are inherently contradictory, i.e. the structure of the positive legal order is based on a series of binary oppositions such as, for instance, the opposition between individualism and altruism or formal realizability (i.e. preference for strict rules) and equitable flexibility (i.e. preference for broad standards). 人不是自由的 • CLS questions law's central assumptions, one of which is the Kantian notion of the autonomous individual. The law often treats individual petitioners as having full agency vis-a-vis their opponents. They are able to make decisions based on reason that is detached from political, social, or economic constraints. CLS holds that individuals are tied to their communities, socio-economic class, gender, race, and other conditions of life such that they cease to be autonomous actors in the Kantian mode. Rather, their circumstances determine and therefore limit the choices presented to them. People are not "free"; they are instead determined in large part by social and political structures that surround them.