Early American Securities — Database Overview

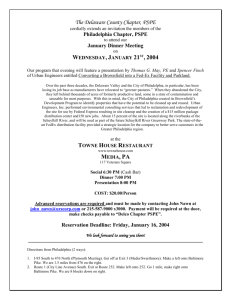

advertisement

Price Quotations in Early U.S. Securities Markets, 1790-1860: Description of the Data Set Compilers: Richard E. Sylla, Stern School, New York University, rsylla@stern.nyu.edu Jack Wilson, North Carolina State University, wilson@gw.fis.NCSU.EDU Robert E. Wright, Winthrop Group, alexanderhamilon@comcast.net Abstract: This document describes a large data set of prices of public securities (equities and bonds) that traded in 9 U.S. securities markets and London between the end of the Revolution and the Civil War. The description includes a basic orientation to the data, its electronic formats, its limitations, and two examples of its potential use. It also includes a brief bibliography and a full list of the periodicals consulted. Acknowledgment: Funding for this data set was provided by the National Science Foundation, grant no. SES-9730692, “America’s First Securities Markets, 1787-1836: Emergence, Development, Integration.” 1 Table of Contents: Project Overview 2 Geographical, Temporal, and Sectoral Scope of the Data Set 3 Electronic Format of the Data Set 5 Data Limitations 8 Data Interpretation Examples 11 For Further Guidance 14 Appendix: Periodicals Consulted 15 Project Overview Over a period of several years, members of the Project, which was composed of two P.I.s (Richard Sylla and Jack Wilson), a postdoctoral associate (Robert E. Wright), a database assistant (Namsuk Kim), and several undergraduate research assistants, scanned early U.S. periodicals (1786-1862) for the prices of public securities -- public and corporate debt and corporate equities. (Details of the sources consulted, the years searched, and the general usefulness of each consulted source are provided in the Appendix.) Not every extant newspaper for every year was searched because the purpose of the project was not to find every extant securities quotation, but rather to find “runs” of securities quotations (daily, weekly, or monthly) in each of the major securities markets (Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Charleston, S.C., New Orleans, London, and, to a lesser extent, Alexandria, Norfolk, and Richmond, Va.), over the core period under study, 1790 to 1850. (Quotations before and after that period were also recorded where time, financial resources, and primary sources allowed. See below for details.) 2 Quotations of inland and foreign exchange, coins and specie, and non-interest bearing cash instruments like bills of credit and banks notes were not included in the data set. Geographical, Temporal, and Sectoral Scope of the Data Set The following table provides an overview of the geographical and temporal coverage of the data set: Market Earliest Latest Number of Weeks of Prices Date Date Recorded Alexandria 1806.0929 1814.0528 246 Baltimore 1803.0214 1862.0531 2,912 Boston 1789.0303 1859.1214 3,792 Charleston, S.C. 1787.0315 1860.1217 2,639 London 1792.0606 1843.1229 1,363 New Orleans 1810.1020 1858.1002 574 New York 1790.0331 1853.1228 3,493 Norfolk 1804.0804 1819.0506 250 Philadelphia 1786.0816 1850.1228 3,148 Richmond 1799.0914 1859.1230 18,417 Total 1786.0816 1862.0531 8,649 Dates are rendered above as in the database, i.e., in the format of year.monthday, where the year is a four digit number to the left of the decimal, months are rendered by the two digits immediately to the right of the decimal, and days find representation in the final two digits. Thus, 1799.0914 indicates a date of 14 September 1799 and 1834.1001 3 represents 1 October 1834. A date of 1800.0100 represents an unknown day in January 1800. The data is divided first by market, then by issuer sectors or types. The types include the following: Issuer Type Number of Issues Banks and Trusts (Equities) 300 Insurance Companies (Equities) 221 Transportation Companies 305 (Equities) Manufacturing, Miscellaneous, 358 and Utility Companies (Equities) Corporate Debt (Bonds) 289 U.S. Debt (National bonds) 135 State Debt (State bonds) 386 Municipal Debt (City and county 176 bonds) Total 2,170 The total number of different issues (2,170) is somewhat inflated by the fact that the project members erred on the side of splitting the same security under separate “key codes” rather than risk lumping disparate securities together under a single key code. For example, we discovered quotations for New Creek Coal, New Creek Iron, and New Creek Water. Given the similarity of the names, there is a possibility that this was a 4 single firm, the full name of which might have been New Creek Coal, Iron, and Water Company. (Contemporary newspapers simply may have shortened the name in three different ways.) Or, there might have been three different companies. Since we were not certain, we kept them separate, assigning them three different key codes -- M-2056, M2060, and M-2066, respectively. Only further research into the issues in question can reveal whether the prices represent one, two, or three different issues. Similar examples abound. Electronic Format of the Data Set We provide the data in two formats, Microsoft Excel and Microsoft Access. Instructions on how to use those programs, or to convert the files to other data formats, cannot be provided here. Users should consult their program documentation or software consultants for operational details. The Access database is designed for researchers who wish to search for particular types of securities, e.g. state debt instruments, or years, e.g. 1818-1822, across all markets. Database assistant Namsuk Kim has included some basic queries to get researchers started, but researchers are not restricted to his efforts. They can create other queries, or port the data to another database, to meet their particular needs. Again, however, they must consult Access’s documentation and/or the IT departments of their home institutions for further instructions and technical guidance. The Excel files are designed for researchers interested in a particular market or security. The index file, SEC-index.xls, contains the key codes and names of the securities, grouped by type: banks and trusts (key code F); insurance (I); transportation (T); manufacturing, miscellaneous, and utility (M); corporate debt (B); U.S. debt (US); 5 state debt (S); and municipal debt (C). Each key code is composed of both the appropriate letter identifier (e.g. S for a state bond) and a dash followed by a unique four-digit number. For instance, F-0560 is the key code of the Chesapeake Bank, C-0506 of Jersey City 6 percent bonds. The data are grouped in files by market. For example, all securities prices for the Richmond market are in the file Richmond.xls. Securities quotations are arranged by type within each file/market. Within each file, the worksheets always follow the same order: the equities of banks and trusts; insurance; transportation; manufacturing, miscellaneous, and utility; then all varieties of corporate debt; followed by U.S. debt; state debt; and finally municipal debt. The number of separate worksheets varies depending on the number of securities. One of the smaller markets, New Orleans, has all of its securities on one worksheet or “tab.” In the other files/markets, all securities of the same type are located on their own individual tab or worksheet. For instance, in the file Charleston.xls, all the companies on the first worksheet are “Banks,” all the issuers on the second worksheet are “Insurance” companies, etc., while all the debt instruments are on the fifth and final worksheet. In the New York file, by contrast, Banks are so numerous (Excel can only handle about 230 columns per worksheet) that they are broken into two worksheets, and each type of debt is included on at least one worksheet of its own. Researchers should use the index file to identify the key codes of the security or securities in which they are interested. If an issuer is not included in the index file, no securities quotations for it were found. If a key code cannot be found in a specific Excel file, that particular security did not trade in that market. In fact, most of the securities in the data set traded in only one of the markets. Major exceptions to this rule are the Bank 6 of the United States (first and second) and U.S. bonds, each of which traded in most (if not all) of the markets. Researchers interested in tracking the prices of those instruments over all markets will have to download each of the Excel files or use the Access database. Researchers should search for an issuer of interest under alternate names. A researcher interested in the Albany Bank, for instance, should also look under Bank of Albany. Similarly, researchers should search for their issuer under multiple categories. This caveat especially holds true for railroads, manufacturers, and miscellaneous companies, quite a few of which engaged in multiple enterprises, e.g. transportation and iron manufacturing, and hence might be listed under either or both the Transportation and Manufacturing categories. Some industrial or utility companies had banking powers and hence might be listed under banks. Water utility the Manhattan Company (F-1390) is a prime example, but not the only case. Finally, the line between banks, trusts, and insurance companies, especially life insurance companies, was often a hazy one. So researchers should look for financial companies of interest under both Banks (key code F-****) and Insurance (key code I-****). Researchers should also bear in mind that a company might have issued both equity (stocks) and debt (bonds) and even multiple forms of each. For example, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O R.R.) sold two forms of common stock (T-0080 and T-0100) and at least 7 varieties of bonds (B-0040 to B-0100). Moreover, researchers should note that preferred stocks, hybrids between equities and bonds, might appear with other equity issues or in the corporate bond list. So researchers should also check the Corporate Debt list for bonds of interest. 7 Data Limitations Project members took pains to ensure that the data represented in the Excel files and Access database are as accurate as possible. The data was closely checked for transcription errors. The quotations, particularly fractions, were at times illegible. Where a price clearly indicated a fraction, but the numerator or denominator could not be ascertained, we assumed a fraction of ½ (transcribed as .5). Prices that were completely illegible were ignored. Due to the inherent limitations of the source material, however, the data set is not entirely “clean.” There are several important limitations to keep in mind. The data set contains: a) gaps where no quotations are available. This occurred, especially early in the period under study or in the smaller markets, where no newspapers carried securities prices. Gaps also appear where some issues/dates of newspapers known to carry securities prices are no longer extant. b) minor inconsistencies in dates both intra- and inter-market. For instance, the data set might have prices of securities trading in Boston on 1 March of a given year, New York on 2 March, Philadelphia on 7 March, Baltimore on 24 February, and no quotations from Charleston. Moreover, the precise nature of the dates was usually not clear, so undoubtedly inter-market inconsistencies exist as well. Specifically, dates sometimes represent the date of the quotation and sometimes the date of the newspaper. c) both transaction data from actual sales and broker-quoted data that may be an average of recent transactions or even the mere estimation of a broker. 8 d) bid-ask prices at times but only one price at others. The single price quotations may be bids, may be asks, may be midpoints, or may be actual transaction prices. Moreover, the actual transaction prices may have been brokered prices or auction prices. Where dealers were involved, generally the bid and ask prices were published. e) quotations of equities that are sometimes ambiguous as they may refer to price ($) or percentage of par. Thus, a quotation of 50 for a particular stock may mean $50 or 50 percent of par. In some instances, we have changed percentage quotations to dollars, rendering, say, a quotation for Bank of North America (F-0250) stock of 110 as 440 because that bank’s par value we know was $400 for much of its early history. Similarly, a quotation of 110 for the Insurance Company of North America (I-0810) was rendered as 11 because the par value of that company’s stock was $10. In many cases, the par value of stock was $100, making the distinction between dollar quotations and percent of par quotations irrelevant. Similarly, all bonds had face values of $100 for quotation purposes, so a quotation of, say, 95, unequivocally means $95 for a bond with a face of $100. The par value of equities, however, was not always ascertained and sometimes changed. In those cases, we have simply transcribed the reported figure. As a general rule, equities in New York were quoted as percentage of par throughout the period of study. No such hard and fast rules apply to the other markets, with quotations changing from dollars to percentage of par depending on the issue and the reporter. Researchers should note, therefore, that abrupt shifts in the quoted prices may be due to actual changes in the stock’s market price, or may simply reflect changes in the stock’s par value or changes in the basis of quotation. For example, an immediate drop from 100 to 30 may indicate a company 9 in serious distress or simply a $30 par stock being quoted in dollars instead of percent par. The drop might also indicate a devaluation of the par value of the stock. The securities price lists from which the data set was created are almost always entirely mute on the causes of such shifts; only exhaustive firm-specific research can reveal its cause. Finally, in the London market, most equities prices are in pounds sterling but some, most notably the Bank of the United States (F-0310), were given in U.S. dollars. f) multiple prices for the same security in the same market. This is relatively rare and is explained by points b, c, d, and e. g) no dividends. A follow-up project is planned that will compile dividend data. Researchers should not despair, however, because there are several important caveats that can guide them to make intelligent use of the data set. 1) All bonds are listed as percentage of par or dollars per $100 face value. 2) The par value of the stock of many corporations was also $100, rendering the price quotations consistent throughout. Par values are not, at this time, provided. Researchers can obtain them from a variety of sources, including state statutes. The par value of the first Bank of the United States was $400, that of the second Bank $100. Note, however, that those and other equities traded before the capital was fully paid in, so a quotation of, say, $80 on a stock with an eventual par value of $100 might actually be par. For clarification of this point, an example is provided below. 3) Bid-ask prices become much more common after 1820. 4) Gaps become much less frequent, particularly in the Big 3 markets (Boston, New York, Philadelphia), after 1820. 10 5) The key features of many bonds can be deduced from their names. “New York City 5s r. 1856,” for instance, refer to bonds issued by the city of New York with 5 percent coupons that matured in 1856. “Chicago 7s, 1880, sewer” were bonds issued by the city of Chicago, bearing a 7 percent coupon, redeemable in 1880, issued for that city’s sewer system. Further information about the bond, for instance whether the coupons were paid quarterly or semiannually or whether it was a general obligation or special revenue bond, generally are not included in the data set, though there are exceptions. 6) Other special features of bonds are sometimes given by their title. Sterling bonds, for instance, were payable in pounds sterling. Some bonds were payable in major money centers like Boston, New York, or San Francisco. Preferred, guaranteed, and mortgage bonds are also generally referenced as such in the name. Data Interpretation Examples In this section, we interpret the price data of two issues as examples by way of further explicating some of the points made above. We start with the Hope Insurance Company (I-0740), a marine insurer chartered by New York State in the 1820s. Its stock chart, drawn from the data set, looks like this: 11 Date Bid Ask As it was a New York company, the price was quoted as percentage of par. Clearly, Hope ran into difficulties in 1825. Sources located in the New York Historical Society indicate that management and governance breakdowns caused the fall. The company sold lowpremium insurance but did not adequately screen applicants; insiders granted themselves cheap insurance on risky voyages. The stock chart of the Bank of New Orleans (F-0235) shows a typical pattern. The gradual paying in of the company’s capital stock caused the run-up in the price of the stock in 1Q and 2Q 1854. The par value of the stock, and hence the market value of the 12 1827.1208 1827.0818 1827.0414 1826.1216 1826.0805 1826.0329 1825.1126 1825.0730 1825.0409 1824.1225 1824.0814 1824.0410 1823.1216 1823.0815 1823.0418 1822.1213 1822.0809 1822.0427 125 115 105 95 85 75 65 55 45 35 25 15 Date Price Stock Chart: Hope Insurance stock, increased as installments on the full par price of $100 per share were made. The dip in prices in 1857 was undoubtedly a result of the financial panic of that year. Stock Chart: Bank of New Orleans 120 100 60 40 20 Date Bid Ask 13 1858.0717 1858.0424 1858.0123 1857.0912 1857.0620 1857.0328 1857.0103 1856.1011 1856.0315 1855.1222 1855.0422 1855.0204 1854.0923 1854.0603 1854.0311 0 1853.1203 Price 80 For Further Guidance Scholars still know precious little about early U.S. securities markets. For background, researchers can consult one or more of the following sources: Sylla, Richard. 2002. “Financial Systems and Economic Modernization,” Journal of Economic History 62:277-292. _______. 1999. “Emerging Markets in History: The United States, Japan, and Argentina,” in R. Sato et al., eds., Global Competition and Integration. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 427-446. _______. 1999. “Shaping the U.S. Financial System, 1690-1913: The Dominant Role of Public Finance,” in Richard Sylla, Richard Tilly, and Gabriel Tortella, eds. The State, the Financial System and Economic Modernization. New York: Cambridge University Press. _______. 1998. “U.S. Securities Markets and the Banking System, 1790-1840.” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review 80:83-104. Wright, Robert E. 2002. The Wealth of Nations Rediscovered: Integration and Expansion in American Financial Markets, 1780-1850. New York: Cambridge University Press. _______. 2002. Hamilton Unbound: Finance and the Creation of the American Republic. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood. 14 Appendix: Periodicals Consulted Key: * = somewhat useful for prices ** = very useful for prices *** = an indispensable source of prices blank = no prices found [ ] = place of publication when not clear from the title dates = range of dates consulted (inclusive) Periodicals: Alexandria Advertiser [Alexandria, Va.], 1806-1808*** Alexandria Gazette [Alexandria, Va.], 1808-1813***, 1814-1820* American Apollo [Boston], 1792-1794 American Beacon & Commercial Diary [Norfolk, Va.], 1815-1819***, 1820-1821, 18241826***, 1827, 1829***, 1832-1833 American and Commercial Daily Advertiser [Baltimore], 1810 American Herald and Washington Gazette [Boston], 1784-1790 American Price Current [New York], 1786*** American Star, or, Historical, Political, Critical and Moral Journal [Philadelphia], 1794 The Argus, Or Greenleaf’s New Daily Advertiser [New York], 1796 Aurora and General Advertiser [Philadelphia], 1793-1794, 1798 Baltimore American and Daily Advertiser; Baltimore American & Commercial Daily Advertiser, 1799-1801*, 1814, 1830-1839***, 1849-1850*** Baltimore American Patriot, 1802-1803* 15 Baltimore Daily Intelligencer, 1794 Baltimore Daily Repository, 1791-1795 Baltimore Democratic Republican, 1802 Baltimore Evening Post, 1792-1793, 1809-1811* Baltimore Federal Republican, 1814 Baltimore Intelligencer, 1798 Baltimore Patriot Mercantile Advertiser, 1813-1830*** Baltimore Patriot Evening Advertiser, 1814 Baltimore Republican, 1802 Baltimore Sun, 1847**, 1850-1853***, 1858-1859*** Baltimore Sunday Monitor, 1796 Baltimore Telegraph, 1797-1800* Baltimore Telegraph and Mercantile Advertiser, 1815** Baltimore Weekly Museum, 1797 Baltimore [Weekly] Price Current, 1803-1830***, 1853-1860*** Baltimore Whig, 1811-1812** Bay State Democrat, 1840** Boston American Traveler, 1838-1839 Boston American Union, 1847-1850** Boston Atlas, 1837-1841** Boston Courier, 1787-1790, 1824-1829***, 1834, 1836-1841** 16 Boston Columbia Centinel, 1790-1791, 1792**, 1793*, 1794-1799, 1810-1820***, 18371840* Boston Commercial Bulletin, 1859, 1865, 1870 Boston Commercial Gazette, 1837-1843* Boston Daily Advertiser, 1830-1836*** Boston Daily Advocate, 1837-1838 Boston Daily American, 1842** Boston Daily Advertiser, 1823-1824*** Boston Daily Bee, 1842 Boston Daily Centinel and Gazette, 1836-1840*** Boston Daily Commercial Gazette, 1830-31*** Boston Daily Courier, 1852/3-1860*** Boston Daily Express, 1838 Boston Daily Mail, 1841 Boston Evening Post, 1781-1784 Boston Gazette, 1810-1815*** Boston Herald, 1859 Boston Herald and Star, 1838 Boston Investigator, 1837-1842 Boston Mercantile Journal, 1835-1838** Boston Patriot, 1815*** Boston Post, 1839-1844**, 1863 Boston Press, 1838* 17 Boston Press and Post, 1840-1847* Boston Semi-Weekly Advertiser, 1840* Boston Shipping List, Prices Current, &c., 1843-1850*** Boston Spectator, 1814 Boston Times, 1794, 1836-1844 Boston Transcript, 1840 Boston Weekly Journal, 1860-1862 Brunswick Gazette a.k.a. The Guardian or New Brunswick Advertiser [New Jersey], 1792-1794 Carey’s Daily Advertiser, 1797 Charleston Carolina Gazette, 1823-1829, 1837-1840*** Charleston City Gazette, 1800-1815*, 1815-1832*** Charleston Commercial Journal and Charleston Wholesale Prices Current, 1841-1842** Charleston Courier, 1803-1849*** Charleston Courier Lettersheet Prices Current, 1833-1841*** Charleston Investigator, 1813-1814 Charleston Mercury and Morning Advertiser, 1822-1833***, 1845-1860*** Charleston Morning Post, 1786-1787 Charleston Oracle, [French language], 1807 Charleston Times, 1800-1804 Cincinnati Emporium, 1824-1826 City of Washington Gazette, 1821 Columbian Herald [Charleston], 1796 18 Comparative Price Current, and European and American Commercial Reporter, [New York], 1827 Complete Counting House Companion [Philadelphia], 1785-1787* Connecticut Courant [Hartford], 1795-1797, 1824-25 DeBow’s Review, 1846-1860 The Delaware and Eastern Shore Advertiser [Wilmington], 1794-1799* Delaware Gazette, 1791-1792 The Dessert to the True American [Philadelphia],1798 The Diary, or Loudon’s Register [New York], 1792*** Dunlap and Claypoole’s American Daily Advertiser [Philadelphia], 1791-1794, 1795** Edinburgh Gazetteer, 1792-1793 [England] Exchange Advertiser [Boston], 1785-1786 Federal Gazette & Baltimore Daily Advertiser, 1797-1800 Federal Gazette & Philadelphia Daily Advertiser, 1793-1794, 1801-1802 Federal Intelligencer and Baltimore Daily Gazette, 1795-1796**, 1798, 1804 Federal Orrery [Boston], 1794-1796 The Financial Register of the United States: Devoted Chiefly to Finance and Currency, and to Banking and Commercial Statistics [Philadelphia], 1838** Finlay’s American Naval and Commercial Register [Philadelphia], 1795-1798*** Freeman’s Journal [Cincinnati], 1797 General Advertiser [Philadelphia], 1790-1794 Georgetown Federal Republican, 1812-1813 Gazette of the United States [Philadelphia], 1790-1794*, 1798-1806** 19 Grotjan’s Philadelphia Public Sale Report and General Price Current [Philadelphia], 1816***, 1820-1823***, 1825-1830*** Hartford Times, 1817-1820 Hope’s Philadelphia Price Current, 1805-1813*** Howard’s Prices Current [Charleston], 1832*** Independent Chronicle [Boston], 1794 Independent Gazette [Philadelphia], 1790, 1793**, 1794* Independent Ledger [Boston], 1786 Lancaster Correspondent, 1799-1801 Liberty Hall and Cincinnati Mercury, 1806-1812 London Gazette, 1787 Louisiana Advertiser, 1820*** Louisiana Gazette and New Orleans Advertiser, 1804-1809, 1810**, 1811***, 1812**, 1813-1818, 1819**, 1820-1826 Lyford’s Baltimore Price Current, 1839-1849*** Maryland Gazette, 1786, 1791 Maryland Hagerstown Gazette, 1809-1814 Maryland Journal, 1786-1794 Massachusetts Magazine, 1789-1794*** Massachusetts Mercury [Boston], 1793-1794 Merchants’ Daily Advertiser [Philadelphia], 1797-1798*** Mississippi Washington Republican [Natchez], 1813-1817 National Gazette [New York or Philadelphia], 1792-1793* 20 Nettle [Boston], 1838-1844 New Jersey Telegraph, McIntyre’s Bank Note List and Prices Current [Jersey City, New Jersey], 1840*** New Orleans Argus, 1824-1826***, 1827*, 1828-1830 New Orleans Bee, 1827**, 1829, 1830, 1833, 1843, 1856 New Orleans City Journal, 1825-1826 New Orleans Commercial Bulletin, 1836, 1839, 1840, 1842, 1844, 1845, 1848-1851**, 1858 New Orleans Commercial Times, 1846-1847** New Orleans Courier, 1822-1823, 1824**, 1826, 1828, 1830, 1832, 1840 New Orleans Daily Delta, 1845-1847***, 1848, 1849, 1850*, 1851-1852, 1853-1854***, 1855**, 1856**, 1857-1858***, 1859, 1863 New Orleans Daily News & Merchants Daily, 1834 New Orleans Daily Tropic, 1843-1844 New Orleans Louisiana Advertiser, 1826-1835*** New Orleans Moniteur de la Louisiana, 1805-1811 New Orleans Picayune, 1838-1848 New Orleans Price Current & Commercial Intelligencer, 1824-1830*** New Orleans Price Current, Commercial Intelligence and Merchants’ Transcript, 18351838, 1839-1850, 1852-1860*** New Orleans True American, 1837, 1839 New Orleans Weekly Bulletin, 1844** New York American Minerva, 1794* 21 New York Columbian Gazetteer, 1793*, 1794* New York Commercial Advertiser, 1799 New York Daily Advertiser, 1790*, 1791***, 1792***, 1794, 1795 New York Daily Gazette, 1791***, 1792**, 1793, 1794**, 1795 New York Evening Post, 1794, 1795* New York Herald, 1794*, 1795**, 1796** New York Independent Gazette, 1788 New York Journal, 1792-1795***, 1796, 1798, 1799 New York Mercantile Advertiser, 1799* New York Price Current, 1797-1830*** New York Register of the Times: A Gazette for the Country, 1796-1798* New York Spectator, 1799, 1821 New York Weekly Chronicle, 1795 New York Weekly Inspector, 1806 New York Weekly Museum, 1789-1797 Norfolk Gazette, 1804-1807***, 1808, 1809*, 1810*, 1814 Norfolk and Portsmouth Herald, 1811, 1824-1825 Norristown Gazette, 1799-1817 North American and United States Gazette [Philadelphia], 1851, 1855, 1863 Pelosi’s Marine List and Price Current [Philadelphia], 1791-1793*** Pennsylvania Herald [Philadelphia], 1785-1787* Pennsylvania Gazette [Philadelphia], 1756-1800* Philadelphia Aurora & General Advertiser, 1799, 1811 22 Philadelphia Commercial List, 1850*** Philadelphia Federal Gazette, 1801* Philadelphia Daily Advertiser, a.k.a. Carey’s Daily Advertiser, a.k.a. Carey’s United States’ Recorder, 1797-1798* Philadelphia General Advertiser, 1793-1794 Philadelphia Evening Chronicle, 1787 Pennsylvania Mercury and Philadelphia Price Current, 1790-1792** Pennsylvania Mercury and Universal Advertiser, 1784-1786 Philadelphia Minerva, 1795 Philadelphia Public Sale Report, a.k.a. Philadelphia Price Current, 1827-1849*** Philadelphia Public Ledger, 1851, 1853, 1859 Philadelphia Universal Gazette, 1798* Political and Commercial Register [Philadelphia], 1804-1819** Porcupines’ Gazette and United States Daily Advertiser [Philadelphia], 1798-1799* Poulson’s American Daily Advertiser [Philadelphia], 1800-1802*, 1833*** Providence Gazette and Country Journal, 1794 Relf’s Philadelphia Prices Current, 1801 Richmond Enquirer, 1804-1810, 1815-1847***, 1848-1850*, 1851-1860*** Richmond Whig, 1837-1848*, 1856-1857*** San Francisco Shipping List and Prices Current, 1852*** Saturday Evening Gazette, 1837-1839 State Gazette of North-Carolina [Edenton], 1796 South Carolina State Gazette and Timothy’s Daily Advertiser [Charleston], 1794, 1799 23 Southern Intelligencer [Charleston], 1822*** Southern Patriot and Commercial Advertiser [Charleston], 1814, 1815-1816***, 18211843*** Southern Quarterly Review, 1842-1857 Sunday Dispatch [Philadelphia], 1851, 1854, 1857, 1860 Temple of Reason [Philadelphia], 1801-1802 The True American and Commercial Advertiser [Philadelphia], 1804, 1805, 1814, 1817 United States Gazette [Philadelphia], 1812 Universal Asylum, or Columbian Magazine [Philadelphia], 1788-1792** Virginia Argus [Richmond], 1793-1803, 1808-1815 Virginia Chronicle [Norfolk], 1792-1794 Virginia Gazette [Richmond], 1790-1792, 1805-1809 Virginia Independent Chronicle [Richmond], 1786**, 1787-1789 Washington [DC] Monitor, 1808-1809 The Weekly Advertiser of Reading, in the County of Berks, 1798 Weekly Louisiana Gazette, 1825**, 1826 Weekly Reporter [Boston], 1819-1827** 24