Building Oral Competency In The L1: Laying The Foundation

advertisement

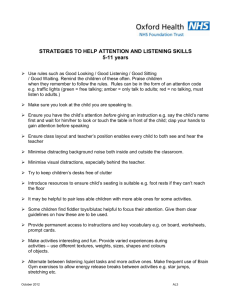

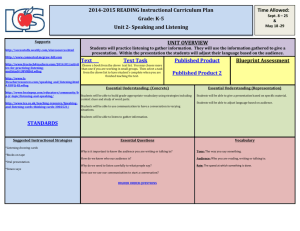

BUILDING ORAL COMPETENCY IN THE L1: LAYING THE FOUNDATION Ellen Errington SIL Asia Area PO Box 12962, Ortigas PO 1605 Ortigas Center, Pasig City, Philippines ellen_errington@wycliffe.net ABSTRACT The child entering school already possesses a growing vocabulary and knowledge base in their home language. They have learned skills by listening, observing and experimenting. These oral skills are a solid foundation for school-based learning. Oral competency continues to develop until about age 12. This competency has a direct connection to the child’s future success as a reader and writer. Even as the child has learned in the home by listening, observing and approximating behaviours, these same techniques are transferable to the classroom as children develop their competencies in the home language and then transfer those skills to learning and using other languages. already know, including the use of their own language, learning can be an interesting and rewarding activity. Oral skills in the home language are also an important bridge to second languages throughout the elementary grades. Research has shown that skills and knowledge transfer freely from one language to another; skills gained in the home language will be accessible to children in other languages, once those languages are learned. 2. WHY THE EMPHASIS ON ORAL COMPETENCY IN THE HOME LANGUAGE? The use of the home language in the classroom encourages connections with the community. In the early grades, the children’s oral skills are built by listening to stories and sharing their own experiences. Games and activities are fun ways of building skills while employing traditional learning styles. It might be assumed that children entering grade one have no need for further instruction in speaking their home language. They are able to communicate their needs and respond to spoken messages appropriately. So why continue to emphasize developing these skills in the classroom? In later grades, children can use listening and speaking activities to support both higher level cognitive skills and second language learning. This session will provide many practical ideas for building oral skills in the classroom. What many educators have failed to take into account is that oral competency continues to develop in the home language until about age 12 [5]. Children need this time to increase their vocabulary (including technical terms) and to develop higher level cognitive skills such as abstract reasoning and discourse features. Language skills develop quite naturally in an environment where they are nurtured [3]. So even when the school day does not include ‘oral competency’ as a subject, appropriate oral activities can support all other academic learning. At the same time, using the home language in academic learning provides a supportive context for further developing the home language to its full capacity. Keywords Oral competency; Scaffolding instruction. 1. INTRODUCTION A sound educational program for children involves every dimension of the communication task – listening, speaking, reading and writing. While reading and writing receive more attention in most schools, the foundation for success in these areas is building competency in listening and speaking. Children entering school already possess a growing vocabulary and knowledge base in their home language. They usually have an innate desire for social interaction. They have heard adults use language in meaningful ways and observed the outcomes and pleasure that meaningful communication brings. They have learned practical skills by listening and observing what others do. They also have experimented with words and actions. Culturally, direct instruction or explanations of what someone is doing may be limited, but still the child has developed a knowledge base around the familiar aspects of his ‘world’ through listening, observing and experimenting. Oral skills developed in the home form a solid foundation for school-based learning. When children can build on what they Oral competency also has a direct connection to the child’s future success as a reader and writer. Gabriele [2] notes that numerous studies have shown a correlation between home language (L1) literacy development and school language (L2) development; her research further points to the important role that L1 syntactic awareness plays in L2 reading comprehension and skill development. [2] The study indeed points to the fact that skills developed in one language become resources for learning in other languages. Even as the child has learned in the home by listening, observing and approximating behaviours, these same techniques are transferable to the classroom as children develop reading and writing skills. Children with weak listening and speaking skills will struggle to read and write meaningfully, regardless of the language issue. Malone [4] illustrates the progression of skills development in this way: Continue building oral and written L1 and L2; use both languages for instruction at least through primary school Continue building oral and written L1 and oral L2 Introduce reading and writing in L2 Continue building oral and written L1 Introduce oral L2 INTRODUCE READING AND WRITING IN L1 1 Figure 1. Progression of skills development This diagram highlights how oral skills are foundational to literacy skills. Reading with meaning naturally grows out of what is heard; writing is an extension of communicating one’s thoughts meaningfully. But note that the chart above is not framed in terms of grade levels; the process is sequential but the time frames at each step may vary. Furthermore, oral skills in the home language form the basis for learning and using other languages meaningfully. In fact, “the level of development of children’s mother tongue is a strong predictor of their second language development [1].” Skills and knowledge are transferable; the home language and other school languages are interdependent and can eventually enrich each other once the second language is learned sufficiently to gain information through it. It stands to reason, then, that the school should help children both develop home language skills and also teach other school languages well. “By contrast, when children are encouraged to reject their mother tongue and, consequently, its development stagnates, their personal and conceptual foundation for learning is undermined [1].” When the home language is not nurtured in the classroom, oral competency will not fully develop. The child will not have the full range of communication skills in the home language and this may have a detrimental impact on learning in other school languages. Cummins further reminds us that, To reject a child's language in the school is to reject the child. When the message, implicit or explicit, communicated to children in the school is "Leave your language and culture at the schoolhouse door", children also leave a central part of who they are-their identitiesat the schoolhouse door. When they feel this rejection, they are much less likely to participate actively and confidently in classroom instruction. [1] 1 3. WHAT ELEMENTS SHOULD BE TAUGHT FOR ORAL COMPETENCY? When teaching in the home language, it is not necessary to focus extensively on rules of the language. Language rules are largely sub-conscious and are learned through hearing the language spoken and by experimentation. Continue building oral L1 Build small children’s fluency and confidence in oral L1 Building oral skills in the classroom is also a useful way to encourage connections with the community and build the confidence of both the children and the community. This is especially true when older community members are not fully literate themselves. In the early grades, the children’s oral skills can be built by listening to stories from the community and sharing their own experiences. Employing learning styles from the oral tradition (listening, observing, and experimenting) is both validating and empowering for the children in the classroom. L1 = the children’s first language, home language, heritage language. This is the language they know best so they should use this language to begin their education. The components of language are the phonological (sounds), the semantic (meanings), and the syntactic (the glue that holds it together) [3]. Most children entering school can produce all the sounds of their home language but may not have an awareness of them. For example, language awareness games might include listening for the first or last sound of a word, choosing the word with a different first or last sound, and thinking of rhyming words. The ability to define word meanings is another skill that can be developed through games. Making word chains (chicken egg nest straw, etc), describing an object with as many words as possible, and explaining a picture or activity are a few ways that children can build their vocabulary and clarify word meanings. The syntactic component is again best learned in the context of stories and games. Children will learn what makes a good story by listening to good stories and subsequently re-telling them themselves. As the teacher tells a story, she/he might stop and ask, ‘What do you think will happen next?’ Perhaps a series of pictures that form a story can be cut into frames and reordered by the children. Older children may start with a story and retell the story in the form of a drama, a poem or a song; procedures, such as how to build a house or cook rice, might be told in the form of instructions to another student. Genishi [3] also suggests a fourth component of oral speech: pragmatics. This is the art of knowing the type of speech which is acceptable in a given context. “Learning pragmatic rules is as important as learning the rules of the other components of language since people are perceived and judged based on both what they say and how and when they say it.” The work of developing oral competency does not end in the grade one classroom. As noted previously, first language development continues throughout the elementary grades. As children learn to read in their home language and later in other school languages, oral strategies continue to play an important part in supporting all learning activities. Walqui [6] asserts that “Rather than simplifying the tasks or the language, teaching subject matter to ELL [English language learners] requires amplifying and enriching the linguistic and extralinguistic context, so that students do not get just one opportunity … but may construct their understanding on the basis of multiple clues and perspectives” [6, p.169]. She suggests six strategies by which teachers can support (or scaffold) learning in a second language. These include: Modelling – children hear a clear demonstration of appropriate language use, such as for describing, comparing, summarizing and evaluating. Bridging – children build on what they already know by talking about the topic before attempting new content and by making the connections to the known. Contextualizing –the teacher sets a reading text or lesson in a real context, such as through the use of pictures, objects or known settings. The teacher makes the new learning relevant to the lives of the learners. Schema-building – We organize understandings by interconnecting clusters of meaning. Prior to reading a text, the teacher can have children skim the main headings and help them develop an (oral) overview of what is ahead. If reading a school language text, the preview might be done in the home language, including an explanation of new words in the text (cf. ‘Content Subjects’ below). Re-presenting texts – children transform one form of text into another, for example, change a story into a drama or poem, change a historical text into an eyewitness account, or change a third person story into a cartoon. Develop meta-cognition – children can learn to manage their own learning by developing strategies for approaching new tasks and learning from past experiences. As can be seen, many of these scaffolding strategies involve oral language skills, and can employ both the home language and other school languages. As these strategies are developed first in the home language, they become a resource to the learner when they approach school language materials. However, code-switching within a lesson should be avoided. The child will develop deeper meanings in each of the school languages when home language is separated from school languages. The use of the home language as a supportive language can precede and follow the school language lesson (i.e., the sandwich lesson); re-presenting texts in the home language might be done during a separate class period. Children follow the Teacher’s instructions, for example, ‘stand up’/ ‘put your hand on your head’/ ‘face the door and clap twice’/ ‘put your left foot on top of your right foot and balance.’ Teacher tells a story and Children clap each time a certain word is said. Teacher tells a story and Children pantomime the action of the story. Speaking skills: Children tell about an activity they have done or an object they have brought to class. Children draw a picture and Teacher circulates in the room to listen as each one describes the picture. Teacher reads a story and Children answer who/ what/ where/ when questions or open-ended questions about the story (such as, “Why did she do that?” “What will happen next?” “Has this ever happened to you?”). Each day, Teacher asks older Children to report on news in the community. Language awareness/accuracy skills: One Child selects an object in the room and says the first sound (ch); other Children will guess what the object is (chair). (phonology component) Teacher recites the beginning of a poem and Children complete it with a rhyming word (“When I jump in the river, I begin to ______”). Teacher says a short sentence and Children respond by clapping for each word or syllable. (syntactic component) One older Child says a sentence that would be appropriate for talking with a friend; a second Child rephrases the sentence in a way that is appropriate for talking with a Teacher. (pragmatic component) Content subjects: Build a sandwich: Teacher begins by previewing a content lesson in the home language, explaining new words and showing the ‘big picture’ ideas. Then the lesson is presented in the school language. Finally Children pose questions or respond to the Teacher’s questions on the lesson in the home language. Alternatively, Children can complete a project based on the lesson, but in the home language (for example, if the lesson is on one of the presidents, the Child will find out about another of the presidents and report back to the class). Children form groups of four; one Child reads a selection of the lesson text, a second Child summarizes the content, a third Child poses two or three questions on the content and the fourth Child answers the questions. The Teacher calls a group of 5 to 8 children to the front of the room. The Teacher presents a math story problem, which the Children act out and thereby solve. Through the use of these strategies, the child benefits three-fold; they increase their home language oral (and written) language skills, their content subject knowledge, and their second language skills. Learning in all three areas becomes integrated and supportive of one another. 4. LEARNING GAMES AND ACTIVITIES FOR THE CLASSROOM This section will provide some sample activities that can nurture oral skills in the classroom and the home. More resources are listed at the end of this paper. Listening skills: Children cover their eyes and listen to sounds around them for one minute. Then Children describe what they have heard. (For example, “Boyet invited four children to play ball at his house. Two children left early to help their mothers. How many children were left to play ball?” Answer is 3.) 6. REFERENCES Historical comparisons: When reading about something that happened years ago, Children work together to prepare a ‘then and now’ chart. The Teacher selects the categories of comparisons and the Children fill in the chart. For example, when comparing what it was like in 1900 to today, the categories might be ‘foods’, ‘ways to get around’, ‘family’, women’s work, and ‘school.’ (based on Walqui’s example) [2] Gabriele, A., et al. 2009. Emergent literacy skills in bilingual children: evidence for the role of L1 syntactic comprehension. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism. 12(5): 533-547, September 2009. Community Connections: Invite a village elder to share stories from his/her childhood. Children can each prepare one question to ask after the speaker is finished or they can draw a picture about something they enjoyed in the story. Older children can interview a grandparent or parent about an event or memory. The Children can present the interview content for the class in the form of a story or drama or first person narrative. Encourage parents to spend time listening to their children each day. Some helpful suggestions are included in the resource list. Prepare and present a home language recitation, song or drama at a community event. 5. CONCLUSION This paper has attempted to show how good oral communication skills in the home language can form a solid foundation for academic success, as well as for learning other school languages. Listening and speaking skills are important components of a complete school program for all children throughout the elementary grades. This paper has offered some practical suggestions for incorporating oral practice into the school schedule in the context of language awareness and content learning. An emphasis on oral home language does not detract from content learning, but rather forms a foundation for learners. Oral language at all grade levels forms a scaffold, or support network. It allows children to gain confidence and competency both as a community member and as a learner. [1] Cummins, J. no date. Bilingual Children’s Mother Tongue: Why is it important for Education? www.iteachilearn.com/cummins/mother.htm [3] Genishi, C. Young Children’s Oral Language Development. www.eric.ed.gov/ERICDocs/data/ericdocs2sql/content_stora ge_01/0000019b/80/1e/22/96.pdf. Accessed January 18, 2010. [4] Malone, S. Planning Community-Based Education Programs in Minority Language Communities, chapter 1. 2006. Unpublished. [5] McLaughlin, B. 1992. Myths and Misconceptions about Second Language Learning: What every teacher needs to unlearn. Educational Practice Report 5. University of California, Santa Cruz. http://people.ucsc.edu/~ktellez/epr5.htm [6] Walqui, A. 2006. Scaffolding Instruction for English Language Learners: A Conceptual Framework. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism. 9(2), 159180. 2006 MORE RESOURCES Behm, Mary and Richard. 2000. Let’s Read! 101 ideas to help your child learn to read and write. ERIC Clearing house on Reading, English and Communication. www.eric.ed.gov/ERICDocs/data/ericdocs2sql/content_stora ge_01/0000019b/80/16/06/7e.pdf Malone, S. 2005. Ideas for activities and games for MLE Bridging Programs. Unpublished. Prince, A. 2006. Promoting Oral Language Development in Young Children. Super Duper Publications. www.superduperinc.com/handouts/pdf/120_oral_language_d evelopment.pdf Waters, G. 1998. Local Literacies. SIL: Dallas, chapter 5 especially.