A Connecticut Mediator in a Kangaroo Court

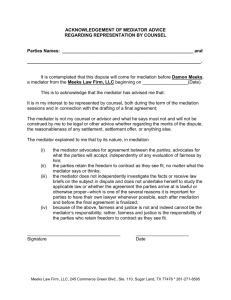

advertisement