Character in Literary Analysis

advertisement

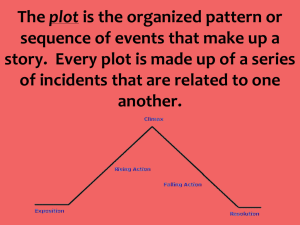

Character in Literary Analysis Character: a verbal representation of a human being as presented by authors through the depiction of actions, conversations, descriptions, reactions, inner thoughts/ reflections, and author’s interpretative commentary. Character Trait: Warning! quality of mind or habitual mode of behavior that is evident in both active and passive ways (i.e., never repaying borrowed money, providing moral support for other characters, reliable, good listener, self-serving, narcissistic). Do not confuse circumstances for character traits! Circumstances may be used as vehicles to reveal character traits, but it is the character’s RESPONSE to the circumstances that reveals character traits. Ways in which authors disclose character… Actions reveal qualities Descriptions (i.e., how the author describes the character) Words and revealed thoughts of the character What other characters say about the character in question Author-as-narrator comments Flat vs. Round Characters o Flat characters are those about whom the reader is given limited information. They are likely to be “supporting actors” in the plot. o Round characters are those about whom we are given more details. They are likely to be either stars or co-stars in the story. Dynamic vs. Static Characters o Dynamic characters change, adapt, or grow as their circumstances change. o Static characters remain the same throughout the story. Adapted from Edgar V. Roberts’s Writing About Literature, 10th Ed. Questions to Raise for Papers on Character Who is the major character? What do you learn about this character from his/her own actions and speeches? From the actions/speeches of others? How else do you learn about the character? How important is the character to the work’s principal action? Which characters oppose the main character? How do the main and opposing characters interact? What are the effects of these interactions? What actions bring out important traits of the main character? Is the character creating the events (circumstances) or responding to them? Describe the main character’s actions. How do they help you to understand him or her? Describe and explain the traits, both major and minor, or the character you plan to discuss. To what extent do the traits permit you to judge the character? What is your judgment? Is the character’s appearance described? If so, what does this reveal about the character? How is the character’s main trait a strength—or weakness? Does the trait become more or less prominent as the story progresses? How does the character recognize, change with, or adjust to circumstances? Is the character lifelike or unreal? Consistent or inconsistent? Some Options for Paper Organization Discuss a central trait, showing how the work brings out that trait. Explain a character’s growth or change. (Stress changes, but don’t retell the story!) Use central actions, objects, and/or quotes to define the character. Adapted from Edgar V. Roberts’ Writing About Literature, 10th Ed. Setting Setting is the natural, manufactured, political, cultural, and temporal environment, including everything the characters know and own. It is used to create meaning. The three basic types of setting are… 1. Private homes, public building, and various possessions 2. Outdoor places 3. Cultural and historical circumstances. Importance of Setting - Augments realism/credibility - Accentuates quality of character - Structures/shapes literary work - Symbolism - Contributes to mood or atmosphere - Underscores irony From Edgar V. Roberts’s Writing About Literature, 10th Ed. Questions to Ask When Writing About Setting o How extensive are visual descriptions? Is detail vivid or vague? o What connections, if any, are apparent between locations and characters? Do locations bring characters together, separate them, facilitate their privacy, or make intimacy and conversation difficult? o How fully are objects described? How vital are they to the action? How important are they in the development of plot or theme? How are they connected to the mental states of the characters? o How important to plot and character are shapes, colors, seasons, times of day, clouds, storms, light/sun, seasons, and conditions of vegetation? o What are the characters’ economic or social conditions (i.e., wealth, class)? How does their condition affect what happens to them, and how does it affect their actions and attitudes? o What cultural, religious, and political conditions are brought out in the story? How do the characters accept and adjust to these conditions? How do the conditions affect the characters’ judgments and actions? o What is the state of houses, clothes, and other possessions? Are there connections to the outlook/behavior of characters? o How important are sounds or silences? To what degree is music or other sound important to the development of a character or action? Adapted from Edgar V. Roberts’s Writing About Literature, 10th Ed. Considering Plot Plot refers to the controls governing the development of the actions in a narrative (i.e., motivation, causation). Determining plot means determining conflict(s) in a story. These conflicts may take the form of Anger Hatred Envy Argument Avoidance Lies Fights Gossip but can also take the form of individual vs. force of nature or society. Look for a dilemma. Plot is directly related to that which causes doubt or tension or brings interest to the narrative. It is that which (or those things which) create(s) uncertainty about a successful outcome. Example: In O. Henry’s “The Gift of the Magi,” elements of plot include a husband and wife who want to exchange Christmas gifts but neither has money to purchase anything. Will they be able to give each other gifts? If so, how, since neither has money? Each of the characters makes sacrifices of themselves that also affect each other. How will the other party accept the sacrifices made? Achtung! Do not mistake plot analysis for plot summary. As a writer, you should assume your audience has read the story and therefore does not need you to retell it. Rather, you should reference points in the story and expound upon their meaning or significance. Adapted from Edgar V. Roberts’s Writing About Literature, 10th Ed. Questions to Consider When Writing About Plot Who are the major and minor characters, and how do their characteristics put them in conflict? How can you describe the conflict(s)? How does the story’s action grow out of a major conflict? If the conflict stems from contrasting ideas or values, what are these, and how are they brought out? What problems do the major characters face? How do the characters deal with these problems? How do the major characters achieve (or fail to achieve) their major goals? What obstacles do they overcome? What obstacles overcome or alter them? At the end, are the characters successful or unsuccessful, happy or unhappy, changed or unchanged, enlightened or ignorant? How has the resolution of the major conflict produced these results? Is the plot arranged to get the reader to favor one side? If yes, on what is your answer based? Is the plot plausible/realistic? Serious or funny? Fair? Adapted from Edgar V. Roberts’s Writing About Literature, 10th Ed. So What’s Your Point? Writing About Themes in Literature Every human expression carries with it a statement about its creator’s philosophy, worldview, or opinion on a given subject. As a reader of literature, one method of appreciation is the search for an author’s main idea. As a writer, one potential angle to take is the reconstruction of the author’s statement. Still, what makes literature such a fascinating topic of conversation is its subjectivity. A thesis that purports to identify an author’s message must be supported much like a criminal attorney supports his or her version of what happened to an audience of jurors. Constructing a Thesis: To say that Chekhov’s The Bear is about love is to identify an idea that is addressed in the play. Constructing a thesis means changing an idea into an argument that can be supported. “Chekhov’s play The Bear demonstrates the idea that love is irrational and irresistible,” is a thesis, because it opens the door to proof and discussion. Values: A standard of what is desired, sought, respected, or treasured. Themes in literature are often built around values. (Example: The treatment of the idea of justice in Glaspell’s play Trifles.) Ideas vs. Actions: Actions demonstrate ideas and make good evidence for a thesis. Students occasionally confuse actions for theses, and the result is an immediate dead-end to the argument. (Example: “The major character, Jackie, misbehaves at home and tries to slash his sister with a bread knife.”) Ideas vs. Situations: Like actions, situations can be used to support a thesis very effectively, but they do not make good theses. Warning! If you find that you are having great difficulty supporting your thesis, the problem may be that your focus is too narrow and that you have mistaken an action or a situation for a main idea or theme. Adapted from Edgar V. Roberts’s Writing About Literature, 10th Ed. Discovering Ideas General Ideas… What ideas do you discover in the work? How do you discover them (through action, character description, scenes, language)? To what do the ideas pertain—individuals, individuals and society, religion, or social/political/economic justice? How balanced are the ideas? Are contradictory ideas presented? If an idea is presented strongly, is it conditional or otherwise qualified? Are the ideas limited to members of any groups represented by the characters (age, race, nationality, personal status), or are the ideas applicable to the general conditions of life? Explain. Which characters represent or embody ideas? How do their actions or speeches bring out these ideas? If characters state ideas directly, how persuasive is their expression—how intelligent and well considered? (An author can use satire to deride a point of view as well. He or she can put the words of his opponent into the mouth of a character who is untrustworthy, stupid, lazy, etc.) How applicable are the ideas to the work? How applicable to more general conditions? Specific Ideas… What ideas seems particularly important in the work? Why? Is it asserted directly, indirectly, dramatically, ironically? Does any one method predominate? Why? How pervasive in the work is the idea (throughout or intermittent)? To what degree is it associated with a major character or action? How does the structure of the work affect or shape your understanding of the idea? What value or values are embodied in the idea? Of what importance are the values to the work’s meaning? How compelling is the idea? How could the work be appreciated without any reference to the idea at all? Adapted from Edgar V. Roberts’s Writing About Literature, 10th Ed.