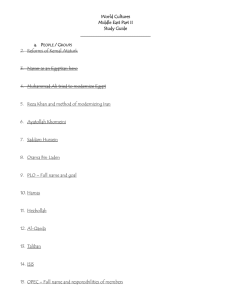

a historic drama

advertisement

Mazyar: a historic drama Sadeq Hedayat and racial supremacy Majid Nafisi Is small moustache writer Sadeq Hedayat’s [1] carries under his nose in some photographs decorative or ideological? Look at any photo album of the era of Reza Shah (1926 – 1941) and you will see many men sporting such a moustache, and analogous to the broad moustache of left or the unshaven look of the Islamists, illustrate their ideological attachments. That was a time when the adulation of Hitler was feverishly spreading across the country – hence the fashion for a Hitler moustache among the young. Many were drawn to Hitler because he was fighting the British colonialists, and thinking that “my enemy’s enemy is my friend” believed that the advance of German forces favoured Iran’s independence. For others, however, the attraction went further and took on an ideological flavour. Hitler’s main characteristic was his racism. Accordingly the Aryans, the master race, had lost their racial purity through intermixing with other races, in particular the Semitic race. Now through the blessing of the Hitlerite movement they must remove the other races and gradually, by means of an increase in the Aryan race and their absolute domination over the rest of the world, save the human race from disaster. For Hitler the Jews were not a religion or even members of a nation, but members of the Semitic race. He was anti-Semitism rather than anti-Jewish. If he had opposed only their Judaism he could force them to renounce this religion. According to the author of “The History of the Jewish People” while the allies militarily defeated Hitler, he was relatively successful in his race war. The Jews of Europe were reduced from 11 to 5 million. The play Mazyar, a historic drama in three acts, was published in Tehran in 1933, the year Hitler became Chancellor. Mojtaba Minovi, Hedayat’s close collaborators in the “Rob’e” literary circle, wrote an extensive prologue in over 70 pages to the 50-page play where he describes the history of the Mazyar uprising against the Abbasid Caliphate [749 – 1258 AD] in Baghdad. Mazyar, an Estahban [2] in Tabarestan [3] was executed AD 838. There is also a short preface signed by both authors. The play is based on a semi-historical, semi-mythical story where Bazist (alias Yahya), an Iranian astronomer in the Abbasid court, invites three Iranian Commanders named Babak, Afshin and Mazyar to rise up against the Islamic Caliphate, revive the Zoroastrian religion and “destroy the Arab race” (page 117). The Commanders fail in their independence movement. Babak succumbs first, betrayed by the brother of Sinbad – another rebel commander. Subsequently Mazyar is captured by the troops of Abdullah bin-Taher, and the plot by the third, Afshin, to assassinate the Abbasid Caliph in Samara is uncovered. The first act takes place in Tabarestan at a time when the rebels are surrounded and on the threshold of defeat. Mazyar’s sole hope is to receive help from Afshin. Ali the son of Raban Tabari, Mazyar’s secretary, and Simru the wise old woman of Mazyar’s camp, both secretly in touch with the Arab army, are trying to get hold of the scroll letter that Afshin has sent Mazyar . The second act takes place in a tavern in Tabarestan, where we find Mazyar with Shahrnaz, a foundling whose family the Arab troops had savagely murdered in front of her eyes. She is playing the harp while he drinks wine and conveys his love to her, telling her that there is no one left in the world for him but her. Suddenly Mazyar’s brother, Kuhyar, who had also betrayed him, bursts into the tavern accompanied by Arab troopers. They arrest Mazyar and ship him off to the caliph court. The third act is in the Samara prison where Mazyar is held. Iranian prison guards are trying to arrange for Mazyar’s escape. Shahrnaz makes a brief visit to Mazyar and then on the belief that her lover cannot escape, takes a poison she had hidden in her signet ring soon. Her death causes Mazyar to lose his senses, become delirious and give up any plan to escape. Thus ends Mazyar’s historic drama in a personal tragic note. Racial supremacy Yet Sadegh Hedayat did not write the historic tragedy to try his hand as a playwright. His aim was to pass on a message which he describes as follows in the forward: “the history and exploits of such celebrated Iranians as Abu Muslim Khorasani, Barmakian, Afshin, Babak, and Mazyar, each of which is a delightful and important chapter in Iranian history, speaks of the bravery, resistance, intelligence, and resourcefulness of Iranians for two decades after the Arab conquest. They show that Iranians continued to fight for their independence, and had not forgotten the splendour and glory of the Sassanian [AD 227-642] era, nor forgotten their racial and intellectual superiority. To write the history of those times and to shed light on these living chapters of Iranian history is one of our vital tasks” (page 11). It is worth noting that the writer does not talk of cultural or national superiority but specifically emphasises the racial superiority of Iranians. These elements approach the aim of supremacy seeking from different angles and therefore propose different solutions to their goal. We must now ask the question that in the Mazyar drama which is the superior race, what are its differences with the inferior race and what are the solutions proposed for racial rectification? In the eyes of Sadegh Hedayat is the Iranian superior? The play is driven from beginning to end by Iran-worship. It might be argued we are witnessing merely a nationalistic viewpoint. But being “Iranian” is not a racial category and in order to look at it from this narrow racial angle we must prove that the writer associates it with white or Aryan races. In the Mazyar drama we frequently encounter Iranians and Romans alongside one another while Arab and Jew are also lumped together (p 122). A clear example of the racial harmony between Iranian and Roman is once the Abassid Caliph has killed the Iranian Babak and the Roman Nanis, he smears both their heads in tar and hangs them side by side outside the city gates (p 123). The superior race is the white Aryan to which both Iranians and Romans belong. As the play is based on the struggle of Mazyar against the Abbasid Caliphate, it appears at first sight that the enemy is the Arab people or Islam. But the more you read the more your realise that from Hedayat’s point of view “Jews” are as guilty in corrupting the Iranian race as the Arabs. It is true that there is much talk of cleansing the “Arab filth” (e.g. p 122), but in many places, including pages 11 and 129 there is open talk of “Semitic filth”. Even in notes at the end of the play the Tabari History [written in 923 AD] is cited where Mazyar always refers to the Muslims as Jews (p138). It may be difficult to imagine this today where the conflict between Palestine and Israel has highlighted the dispute between Islam and Judaism, but if we return to the conditions pertaining to the inter-war years, when Mazyar was written, an understanding of the issue is made very easy. From the ethnic point of view Arabs and Jews both belong to the Semitic race (p 125). It would be natural for Hedayat, who sees a return to ancient Iran as a sacred ideal, to see a connection between the genocidal policies of Hitler against the Jews and the struggle of ultra-nationalist Iranians against the Arab element. To highlight “the Jews, this race worse than Arabs” (p 98) as the enemy of Iran is in fact the main message of this play. In act one we are introduced to Ali the son of Raban Tabari, Mazyar’s secretary, and Simru, the old woman in his organization. Both were previously Jews. Simru’s real name is Sara, and the secretary was a Jew before converting to Islam. According to Shadan on page 93 and according to Mazyar on page 95, it is these two who gnaw away at the Iranian resistance movement from the inside, and pave the way for the destruction of the anti-Arab movement. In act one we discover that they had poisoned Mazyar’s food and are also trying to lay hands on the letter Afshin has written to Mazyar in order to assist Afshin’s arrest purge him from the caliph’s administration. In act two, Simru listens through a secret door to the conversation between Mazyar and Shahnaz in the tavern and thereby discovers Afshin’s plot against the caliph due to take place on the day of the Iranian Mehregan festival [4]. Thus although the Aryans and Jews belong to two religions, from an Iranian racist perspective, such as that of the author of Mazyar, they both belong to an inferior race, Semites, and should be regarded as a single enemy. Racial annihilation The next question is what was Hedayat’s solution for racial correction? How could the superior Iranian-Roman race save itself from the inferior Arab-Jewish race? Here the talk is of bloody cleansing and not cultural or even ethnic cleansing. Corruption was caused by racial intermixing (p 95). It is the half-Iranian half-Arab race that everywhere has sullied Iranian purity and caused the Arab and Islamic domination (p 11). If a person has Islamic blood from only one parent he or she assumes the meanness of the Arab (p 116). In addition to Ali, son of Raban and Simru, there are two more examples of this mixed parentage. One is Kuhyar, Mazyar’s brother who betrays him, and the other is Hassan ibn-Hossein who is a commander in the army of Abdollah ibn-Taher [5]. For Mazyar the reason for his brother’s betrayal is that his mother was an Arab slave (p 112), and that he had been corrupted through intermarriage with Arabs (p 111) and alliance with Jews (p 113). Hassan ibn-Hussein also comes from an Iranian-Arab mixed parentage. In the face of blood contamination there is but one solution: blood settlement. The author unequivocally states that blood cleansing is the only possible through blood letting (p 130). The model for Mazyar is his grandfather Vandad Hormoz, who when he was governor [6] ordered Iranian women to hand over their Arab husbands, who were then hanged (p 96). Hedayat was writing at a time when in Germany the policy of exterminating Jews had begun. Hedayat of course does not confine himself to racial superiority when he describes the era of Mazyar. He adds cultural and national superiority to the brew. For example he calls Zoroastrianism the “white religion” contrasting it with the “black religion” of the Semites (p 98). He writes of the “murderous Islamic flood” (p 9) and the “Arab Gog and Magog” (p 11). The Arabs and Muslims are enemies of industry and civilisation (p 118). The Muslims even copied the architecture for their mosques from Iranians. Their religion is full of superstitions. The Arab is base and barefoot (p 120). Their clothes is chapi agal – derived from the nosebag of beasts of burden (p 130). If they defeated Sassanian Iran it was not through military prowess or the popular attraction of their egalitarian promises, but through guile and scheming (pp 11 and 108). And despite trickery they are stupid and dim-witted (p 123). They are unrivalled in cruelty and all they do is severe hands and feet and torture (pp 106 and 131). They are greedy and lustful: while the Roman Nanis dies of hunger only after three days in prison, Musa ibn-Hareish, imprisoned because of adultery with the Caliph’s wife, has such a thick neck after three months in prison that they cannot severe it with an axe (p 122). Yet these same Arabs are presented as “satanic race of snake eaters” (p 10), rat eaters (p 100), lizard eating camel herdsmen (p 98) and hungry beggars (p 105). They cheat and are hypocrites in religious guise such that Hassan ibn-Hossein would drink wine out of sight of his colleagues (p 115). Thus Arabs are drained of all human attributes and become demons whose destruction and ethnic annihilation becomes easy for those believing in racial superiority. Interestingly in Hedayat’s tale, Mazyar and Afshin try to popularise their revolt to annihilate the inferior race through myth making. They chose the Mehragan festival [see footnote 4], the same day the legendary Kaveh Ahangar revolted against the despot Zahhak [7]. Here Sadegh Hedayat apparently forgets that according to the poet Ferdowsi himself, Rustam the Iranian hero, was from his mother’s side Arab. What seems important for the author of Mazyar is the creation of a new myth for the racist movement that had occupied his mind, and that of many intellectuals of his generation in 1933. Once acquainted with Hedayat’s racist and anti-Semitic views in Mazyar you ask yourself how can a man who wrote The Benefits of Vegetarianism and the story Vagrant Dog, and who was so sensitive to the killing and torment of animals, could be so insensitive to the bitter plight of millions of humans merely because they have a different religion or language? In my view the problem is in intellectual intolerance. Adolph Hitler was also a vegetarian. Intellectual bigotry is not just apparent in the Mazyar play. Extremist Iranism is one of the main characteristics of Hedayat’s literary creations during his first period as a writer. One can see examples in the play Parvin, Daughter of Sassan (1930), stories such as The shadow of the Monguls (1931) and The last smile, the satires Al Besat al-Islamieh ilal bilad al-Faranjieh (1930) and Morvarid Cannon, and such investigative works as Owsaneh (1931), Nirangestan (1933), The Songs of Khayyam (1934), and the travelogue Isfahan, Half the World (1932). Omar Khayyam’s apostasy is presented as an example of the revolt of the Aryan spirit against Semitic beliefs. The superstitions of the people of Iran is ascribed to their intermixing with Arabs and Jews, and the growth of the architecture in Isfahan during the Safavid era [1501-1732] is credited to a return to Sassanian Iran. No crocodile tears? Like many of his generation, Hedayat was drawn to the Tudeh party after Reza Shah was removed from power by the Allies in 1941 because of his collaboration with Germany. Hedayat went on to write social stories such as Haji Agha and Tomorrow, and even travelled to Tashkent, capital of Uzbekistan, at the invitation of the Soviet authorities. Yet during this second phase he never officially repudiated the racial supremacy worldview of his earlier books. Recently my colleague Naser Pakdaman published a hitherto unknown piece by Sadegh Hedayat in the 14th issue of the Journals of the Association of Iranian Writers in Exile, It was called Crocodile Tears and appeared under the pseudonym KZ in the first issue of Rahbar, the official organ of the Tudeh Party in the winter of 1942. In his introduction Pakdaman writes: “The importance of Crocodile Tears is that it gives a different perspective to the “nationalist” beliefs of Sadegh Hedayat. The latter writes “we are no different from others. We are a nation like any other nation. Moreover in today’s world setting ‘what I had, what I had’ is of no import, only ‘what I have, what I have’. We have to see what we have today and what we are going to do” (p 183). Moreover Hedayat mocks the ‘20 year’ era of Reza Shah (p 180) and even hint at the ‘lackey who has risen in Berlin’ (p 193). Unlike the spurious Iranian nationalists, Hedayat does not see Iran as the only ancestor to world civilisation (p 188) and gives due credit to the Greeks, Romans and Indians in the march of human civilisation.” Yet the writer of the Crocodile Tears nowhere mentions Arabs or Jews and the role the Semitic race has had in the development of human knowledge and culture. For that reason this article cannot be taken as an honest and deep-rooted facing up to the racist views Hedayat held in his first period of writing. If Sadegh Hedayat had not, even in the last years of his life, criticised his earlier anti-Semitic views, why do we need to do so almost 70 years after the publication of Mazyar? Should we emulate some Hedayat scholars and blame his racism on the particular social and political conditions of the Reza Shah era, and ignore the role played by such prominent intellectuals as Mojtaba Minovi, Bozorg Alvi, Sh. Partow, Zabih Behruz, and Ebrahim Pour-Davood in propagating these pernicious views. A leading scholar such as Mohammad Ali Homayoon Katuzian in his book Sadegh Hedayat, From Myth to Reality wrote thus on Hedayat and his compatriots: “To compare them to Nazis and European fascists and their Iranian counterparts would be mistaken. Their words were harsh and their views simple and warped. But their intent was untainted and their political behaviour is above reproach and was the destiny of most men who were in similar time, place and social position” (p 111-2). Yet if Iranian intellectual society had criticised its anti-Semitic and Aryan-worship views immediately after the end of the Reza Shah era society as a whole would no doubt have benefited. It would have been a big step towards rejecting totalitarian and despotic views. Ideas of freedom would have taken firmer roots in our oppression-laden land. Today too, because of people’s hatred of the religious despotism ruling our country, distrust of Arabs and Arabism has grown. Iranism and Aryan worship is becoming more acceptable. However, for any intellectual who understands that the way to oppose religious despotism is through disseminating freedom of thought and expression, it is more important than ever today to confront the evil of racial superiority and the experience of the era of Reza Shah. 16 January 2003 Footnotes by translator: 1. Sadeq Hedayat is one of the pioneers of modern Iranian literature. His Blind Owl was one of the first novels written in Farsi and has been translated into many languages [see the article by Mansur Khaksar in this issue]. He committed suicide in exile in Paris in 1951. 2. Espahbod: Sassanian provincial administrators. 3. Modern Mazendaran province in northern Iran] 4. Jashne Mehregan one of the most important Iranian pre-Islamic annual festivals around autumn time. 5. An Arab general to the Abbasid court. 6. Espahbod see note 2 7. The mythical revolt by Kaveh, a simple blacksmith, against the cruel and despotic king Zahhak as described in Ferdowsi’s [died 1032 AD] epic poem Shahnameh [the book of kings]