8.4 Causes of the Depression

advertisement

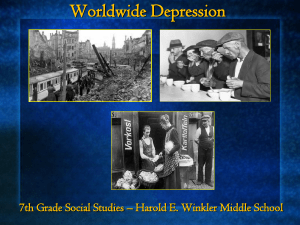

Causes of the Depression Americans have often blamed the stock market collapse for their plight during the 1930s. The blame was not entirely misplaced. The Crash wiped out billions in paper wealth and replaced the buoyant optimism of the New Era with caution. It badly frightened the people who made the economy's decisions to invest. By 1932 gross private domestic investment had sunk to one-ninth the 1929 amount. The Crash also destroyed the confidence of consumers, who tightened their belts and delayed buying. if the blind optimism of stock market investors during the New Era had helped cause the Crash, the equally blind pessimism following it prolonged the Great Depression. The stock market tumble, however, was only the most visible cause of the economic collapse. The 1920s had been a time of economic growth, but that growth had depended on an unstable balance of factors. New markets for automobiles, radios, refrigerators, and other durables had induced businesses to invest vast sums to expand production. In addition, governments had poured more billions into roads, bridges, and other capital improvements, while private citizens, now able to rely on the family automobile, for quick transportation to city jobs, bought homes in the burgeoning suburbs. Pushed by the consumer durables surge, construction, steel, cement, petroleum, rubber, and scores of other industries boomed, creating jobs and income for millions of urban Americans. Most people came to see the new affluence as normal and to assume that it would never end. But they were wrong, of course. The end of the surge was inevitable. With 50 percent of the nation's income going to only 20 percent of its families, the market for expensive consumer durables, though wider than in the past, was limited. When all those who could afford the new car or the new radio had satisfied their needs, demand had to decline. By 1927 or 1928 these effects were already been felt and manufacturers were beginning to cut production and lay off workers. spiral was now set in motion: Fewer new orders for goods led to fewer jobs; the unemployed in turn could not buy what the factories produced and so orders further declined. Overall, the massive push to invest, which had fed the economy. since World War I, had lost its momentum. The international economy also contributed to the decline. The burdens war debts and tariff barriers were becoming harder to bear as the decade near its end. England and France had emerged from World War I owing enormous debts to America. To pay they needed to export their own goods to America. Bu as we have seen, the United States raised tariffs during the 1920s, making it increasingly difficult to sell foreign goods to Americans. The $33 billion indemnity imposed on Germany by the postwar Allied Reparations Commission could make up the payments gap with America. But the Germans could not pay it, and in two successive stages (the Dawes Plan, 1924, and the Young Plan, 1929) the payment were pared down and stretched out. For a while, large-scale lending by America banks took up the slack, enabling the former Allies to buy American goods o credit. Indeed, American banks invested heavily in nations around the world helping to fuel the worldwide boom. By 1928, however, the bankers were beginning to have second thoughts about foreign loans. The whole shaky structure c foreign trade was now in jeopardy. THE GREAT DEPRESSION. The collapse of the stock market triggered an avalanche of disaster. Credit became tight, and interest rates soared. The Federal Reserve Board could have eased the situation by lowering interest rates, but took no action. To save themselves, banks cut off credit to businesses and foreign borrowers. All trade slowed, but foreign commerce, which had been sustained by constant infusions of American credit, was hit especially hard. To sustain their exports and reduce their imports, many nations imposed strict trade barriers and raised tariffs. The world's trading nations had used a currency exchange system pegged to the price of gold that had encouraged international trade and investment. Now, many abandoned the gold standard, allowing the values of goods and currencies to fluctuate wildly and further disturbing international commerce. Under the combined blows of trade restrictions and currency instability, commerce among the world's nations declined precipitously. By mid-1930 the Great Depression had been exported from America and was virtually worldwide. Meanwhile, the domestic banking system faced collapse. As the economy worsened, frightened depositors rushed to withdraw their savings. Bank after bank failed as "runs" forced even solvent institutions into bankruptcy In November 1930, a total of 256 banks with deposits of $180 million closed their doors. Most severely affected in this round were the financial institutions of the farm areas, where bank failures had been numerous even in the 1920s. The decline of consumption was a key factor in worsening and prolonging the Depression. The collapse of the bull market frightened consumers of luxury goods, whose sense of well being depended on their paper profits. But even ordinary consumers, who had not "played the market" during the twenties, turned timid after the Crash and ceased to make their indispensable contribution to the economy. Here the nation's very affluence hurt it. In former times, when most consumers' income went for necessities, they had limited choices whether to spend or not. But in this rich era they could put off vacation trips and decide not to buy new radios, cars, or refrigerators. The most durable of all durable goods-houses-could be deferred the longest, and new housing sales dropped off disastrously. Deferring purchases and investment at first was largely voluntary, but it soon became inescapable. As unsold inventories built up in stores and showrooms, retailers reduced their orders to manufacturers and suppliers. They in turn lowered their investment goals, cut back on production, slashed wages, and fired employees. Unemployment shot up. By the end of 1930 over 4 million men and women were out of work. Many more were working part-time or for sharply reduced wages. Families whose breadwinners lost their jobs cut their budgets to the bone. Total demand now declined still further, establishing a vicious downward spiral of economic deflation. If commodity prices had fallen as far and as fast as consumer income, goods might have continued to move, and workers might have kept their jobs. In areas where there were many competitive producers prices did fall. Between 1929 and 1933 agricultural prices dropped 56 percent, while output remained virtually the same. The plunge was unfortunate for farmers, but it kept farm production and farm employment high and prevented widespread hunger. In segments of the economy where competition was limited, however, prices stayed high. Automobiles remained expensive-about $600 for the average vehicle both in 1929 and in 1932. Because most people could not buy cars, production-and employment-fell. By 1932 automobile output had dropped to 25 percent of the 1929 figure, and the number of automobile workers had declined to under 40 percent of the 1929 total.