Workplace Literacy Fund

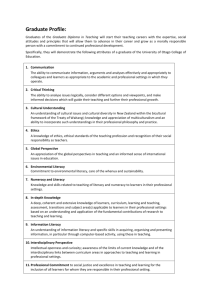

advertisement