hankins Baptists and the Common good

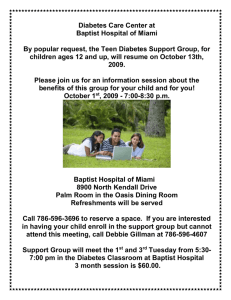

advertisement

1 Four Kinds of Baptists, One Common Good? Barry Hankins, Baylor University When I was originally asked to come to this meeting and speak on Baptists and the common good, I thought about doing something covering the whole sweep of Baptist history. Kind of like snapshots of different ways Baptists have considered the common good over the past four hundred years. This filled me with dread, however, largely because I’m not really a Baptist historian. I’ve never done any primary research in early Baptist history, and the thought of spending time reading Smyth, Helwys, Roger Williams, and John Clark just felt like too big a project for the time I had. I found myself wishing that my topic was twentieth-century evangelicals, fundamentalists, and the common good. I knew that if this were the case I could spin out something interesting and perhaps provocative with some confidence that I was not making a gaffe of some sort. I finally decided to do what both scholars and politicians often do. Take the reporter’s question, and give whatever answer I want. Or, in this case, take the theme of the conference, then just talk about what I know. So, I decided to focus on the twentieth century and to incorporate some of my own research on fundamentalist and evangelical Southern Baptists with the research of some of my doctoral students and with the work of David Stricklin in his book Genealogy of Dissent. What I initially proposed to argue was that we can identify four kinds of Southern Baptists in the twentieth century—fundamentalists, moderates, conservative evangelicals, and progressives—and that all four have pretty similar, almost identical, conceptions of the common good. At least when it comes to big issues on 2 which Baptists pride themselves on making a cultural contribution. This twentiethcentury conception of the common good, at its worst, I believe, has been formed more by the relationship Southern Baptists have with American culture than by any serious biblical formation or contact with a more historic form of Baptist witness. As I worked through the paper, I’ve had to revise my thesis somewhat, as you will see, because I’m no longer convinced that the progressive dissenters shared the same culturally assumed conception of the common good that the other three groups shared. So, here’s a little trick you may not have learned yet. When you have to give a title of an address that you haven’t written yet to a conference organizer, then you write the address and find that your original thesis doesn’t hold up, just put a question mark at the end of the title. Then, at the conference, start by telling the audience, “There was supposed to be a question mark at the end of my title. Apparently, it was left off when the conference program was printed.” The REAL title of my lecture is “Four Kinds of Baptists, One Common Good?” First, a caveat: To be fair, I need to note that I’m focusing on the “at its worst” aspect of Baptists and the common good. I will concede that all four of these kinds of Baptists have done much good in society. Like other American evangelicals they instinctively and intuitively care about their neighborhoods, towns, individual states, and the American nation as a whole. While sometimes on the wrong side of important issues, especially race, Southern Baptists have exhibited a deep sense of concern and care for the common good of those around them. Earlier this summer my mother in law was staying with us for a few days and asked me about the Oxford trip and what my role would be. Now, my in-laws spent their 3 careers owning and operating one of the largest independent Christian bookstores in America and were very active in the Christian Booksellers Association, various evangelical publishing outlets, and other institutions in the evangelical world. They are Church of Christ by background, of a fairly progressive sort. Which means they let their daughter go to Texas Tech rather than Abilene Christian, not to mention allowing her marry outside the faith and even join a non-Church of Christ denomination—all without ever suggesting that she isn’t going to heaven. My in-laws have retired and moved to a ranch outside the very small town of Forestburg, Texas, population 47 with several hundred more in the sprawling Montague County. The tiny town of Forestburg, about two square blocks, has a Baptist Church, a Methodist Church (??), and a Church of Christ. When I told my mother-in-law that our topic here at Oxford would be Baptists and the common good, she had an immediate response. She said, “The little Baptist church in Forestburg sends a bus all over the county picking up children from poor rural familes that don’t attend church. Because of the Baptists these kids learn about the bible and have recreational and educational opportunities they wouldn’t otherwise have. They’ll be better people and the county will be a better place because of this work. For what it’s worth, that’s what I think about when I think about Baptists and the common good.” Not a bad report from a non-Baptist, and not a bad reputation to have. That’s what I’m conceding—that all over Baptist history has been this desire to reach people with the gospel so that they are converted, become better people, and help form better communities. Like other evangelicals, Baptists have been pretty good at DOING. As 4 Mark Noll has written about evangelicals, “The tendency of American evangelicals, when confronted with a problem, is to act”—in other words, to do something. But, I want to focus on how Baptists think about what they’re doing—how they understand their social action, justify it, how they try to motivate each other to press forward with work done in behalf of the common good. This part of Baptist history hasn’t been very good, at least since the dawn of the twentieth century. Baptists fit the first part of Noll’s quote above, but they also fit the second half of the quote. Here’s the whole quote: “The tendency of American evangelicals, when confronted with a problem, is to act. For the sake of Christian thinking, that tendency must be suppressed.”1 Applied to Baptists, what this has meant is that even Baptist intellectual elites have tended to think about what needs to be done and how best to accomplish these tasks, without deep enough reflection about theology and political theory, especially pertaining to the nature of the church. There has been a tendency to take certain cultural ideas for granted, the result of which has been that as Baptists attempt to accomplish something positive for the common good, they have—again, at their worst—tended to confuse the common good of culture with what it actually means to be Baptist, and sometimes with what it means to be Christian. And this has done real harm to the Baptist witness in the late twentieth and early twentyfirst centuries. For my four kinds of Baptists—fundamentalists, moderate, late twentieth-century conservative evangelical, and progressive dissenters—I will use an individual or two to illustrate each kind—J. Frank Norris as the fundamentalist, E.Y. Mullins and George Truett as the moderates, Richard Land as the conservative evangelical, and Clarence Jordan and others of his lineage as the progressive dissenters or dissidents. I want to 5 emphasize again that with each I’m looking intentionally for the ways that while DOING in behalf of the common good, they failed to think sharply about either common good or their own identity as Baptists and Christians. J. Frank Norris Norris, as many of you know, was the pastor of First Baptist Fort Worth for most of the first half of the twentieth century. I believe he was one of about four of the most influential fundamentalists in America in the first generation of American fundamentalism, which would be from the Scopes trial of 1925 until Norris’s death in 1952. He built First Baptist Fort Worth into one of the largest churches in America, with about 12,000 members by 1940. The church took up an entire city block in downtown Fort Worth. It was an early version of the megachurch. In addition to his Fort Worth enterprise, at the height of his career Norris took over as head pastor at Temple Baptist in Detroit and led both churches from 1935 until 1950. Temple also had about 12,000 members, which allowed Norris to boast, probably accurately, that with roughly 25,000 parishioners he had more people under his pastoral care than any other preacher in America. Norris was a militant, rabble-rousing fundamentalist. He was always on the attack against something—theological modernists, Catholics, Communists, evolutionists, other Southern Baptist leaders. You name it; Norris attacked it. Norris was infamous nationwide, if for no other reason than the fact that he shot and killed a man in his own church office in 1926 and was subsequently tried for murder. He got off on a self defense 6 plea because his attorney was able to convince the jury that Norris had reason to believe that the man he shot had come to his office to attack him. Norris testified that he feared for his life, even though the other man was unarmed. The victim’s name was D.E. Chipps. When I covered this part of Norris’s life in the first draft of my dissertation, and came to the place where Norris shot Chipps three times, my dissertation adviser wrote in the margin, “Good Bye Mr. Chipps.” What we need to focus on for a few minutes today is Norris’s approach to public life. Norris began his career as something of an urban reformer. This was not unusual for big-city fundamentalist pastors of that era. William Bell Riley in Minneapolis was much the same, as were some others such as C.E. Mathews in Seattle and John Roach Straton in New York City. Norris, for his part, regularly called on Fort Worth’s city fathers to eradicate prostitution, more stringently regulate or shut down the saloons, and end graft and corruption. Moreover, First Baptist Fort Worth had soup kitchens, a clothing bank, recreational and educational programs—many of the features of the institutional churches of the northern social gospel. On a national level Norris crusaded against evolution, alcohol, Catholicism, and Communism. His support for prohibition was second to none and this issue led to his first major foray into national election politics. When the wet Catholic Al Smith ran for president in 1928, Norris barnstormed Texas and Oklahoma campaigning for Herbert Hoover, believing that the election of a Republican was the only hope to salvage prohibition. There were all sorts of reasons Norris didn’t like Smith, of course. In addition to the liquor issue were Smith’s Catholicism and his connection to the corrupt machine politics of Tammany Hall in New York City. But on the liquor issue and later 7 on communism, Norris clearly had a sense that a Baptist pastor had a responsibility to protect the common good, even nationally. Norris seemed to be genuinely concerned about the effects of alcohol and the potential for prohibition to curb the problems associated with alcoholism. He was also vigilant, even bellicose, in defending American democracy from the possible inroads of communism, both real and imagined, and Catholicism, as it was typically understood in his time. In short, in a variety of areas, Norris just assumed that a Baptist pastor of a large urban church was a public figure, a civic leader, and that the church was a public institution. As an individual, city pastors stood alongside mayors, city managers, councilmen, police and fire chiefs, and other public officials as part of the structure of society. All of these individuals and institutions had responsibility for the common good of the city of Fort Worth. Nationally, Norris thought of himself as working hand-inhand with U.S. Representatives, Senators, and even presidents to protect America. Norris rarely defended his role as a public reformer because it was taken for granted that this was a part of his job description. When he saw a problem, his tendency was to act, or at least shout. Truett and Mullins At the same time that Norris was pastor of First Baptist Fort Worth, George Truett (d. 1944) was pastor of First Baptist Dallas. They were rivals, largely because Truett was a Southern Baptist insider, a spokesman and statesman for the mainstream of Southern Baptist life, while Norris was by choice an outsider, constantly on the attack against those 8 in power in the SBC, whom he called “the Sanhedrin.” On one occasion in 1940 Norris sent a nasty letter to Truett and tried to time its delivery for Sunday morning just before Truett entered the pulpit to preach. The telegram was intercepted by an associate whose family held onto it for decades before turning it over to the library and archives at Southwestern Seminary. In the letter Norris alleged that all Truett’s efforts to derail the Norris juggernaut had been in vain. Norris said his success had defied Truett’s prediction that Norris’s career would not prosper. While Norris and Truett were holding forth in Texas, and both on a national stage as well, the erudite Mullins was president of the flagship Southern Baptist Seminary in Louisville, until his death in 1928. Although Truett and First Baptist Dallas occupied a place in Dallas city life much like that of Norris and his church in Fort Worth, with Mullins and Truett I want to focus briefly on their views of Baptist democracy and its relationship to American politics and culture. Here I am relying largely on the dissertation of my former student Lee Canipe. Lee did his dissertation on Mullins, Truett, and Walter Rauschenbusch—specifically on the degree to which all three Baptist leaders took for granted the notion that Baptist democracy and American democracy were virtually synonymous. We’ll leave Rauschenbusch for later in the week and focus primarily on a some representative statements from Truett and Mullins. In a 1911 sermon entitled “God’s Call to America,” that would be a chapter in Truett’s 1923 book by the same title, the venerated Dallas pastor said this: “The triumph of democracy, thank God, means the triumph of Baptists everywhere.”2 Far from an anomalous utterance on some isolated July 4th celebration, this equation of American democracy and Baptist democracy was Truett’s and Mullins’s studied view. In a later 9 sermon published in 1932, Truett said that democracy “is the goal for this world of ours—both the political goal and the religious goal. . . . [D]emocracy is the goal toward which all free people must travel. . . both in government and in religion.”3 In his famous sermon on the steps of the U.S. Capitol building in 1920, a sermon that subsequently went on to mythic status in Southern Baptist history, Truett further cemented the connection between church and state, even as he called for the separation of church and state. He concluded his sermon by saying, “Standing here today in the shadow of our country’s Capitol, compassed about as we are with so great a cloud of witnesses, let us today renew our pledge to God, and to one another, that we will give our best to church and to state, to God and to humanity, by his grace and power, until we fall on the last sleep.”4 Notice here the twin commitment to church and state. Moreover, when he mentioned the “cloud of witnesses,” it was not altogether clear who they were because he had referred Baptist forefathers and the American founders in the sermon. His reference to our commitment to “God and humanity,” seems to suggest a commitment to the common good. Mullins was no less an advocate of the convergence of American democracy and Baptist ways. In a 1911 article he wrote, “The Baptist type of religion is most fundamentally in accord with the ongoing of the world toward democracy.”5 In his famous Axioms of Religion, Mullins made no attempt to develop theologically his religiocivic axiom, which is “a free church in a free state.” Instead of developing this axiom theologically, as he did the other five, Mullins turned instinctively to the American principle of church-state separation and drew this theological axiom from the U.S. Constitution. This axiom, he wrote, “which states the American principle of the 10 relationship between the Church and State is so well understood and is accepted by the people of the United States so generally and heartily that it is unnecessary to spend time in pointing out at length what the axiom implies.” Later, he noted that this American view came from “the fundamental facts of human society and the Gospel.”6 Moving from the religio-civic axiom to his social axiom, Mullins rejected what he viewed as a “mere social Christianity” and argued that Christianity must be both individual and social, with the social being a by product of the individual. “To regenerate the individual is the sole condition of permanent moral progress in the social sphere.” Then, summarizing this final axiom, (again, the social axiom), he made this observation: “It is the essence of Christianity to send a man after his fellows. The Christian who understands the meaning of his religion, therefore, will be a force for civic, commercial, social, and all other forms of righteousness. Thus Christianity in America will become the religion of the State, although not a State religion.”7 Indeed, it goes on and on, as Mullins later in the book Axioms of Religion wrote, “We may regard American civilization as a Baptist empire for at the basis of this government lies a great group of Baptist ideals.”8 In aftermath of WWI, in the wake of the defeat of the autocratic regimes of Europe, moderates of the 1920s such as Truett and Mullins were flush with the potential for Baptists to lead in the promotion of democracy. They believed that the demise of autocratic government would go hand in hand with the demise of sacramentalism, opening the way for the free church tradition to ascend hand in hand with American democracy. Speaking at Mullins’s silver anniversary celebration at Southern Seminary in 1924, Truett said, “Autocracy must pass, is passing, and with it will go sacramentalism 11 and sacerdotalism, the grave clothes of a moribund and decadent faith.” Of course, this “moribund and decadent faith” was Catholicism. The statement was an example of the anti-Catholicism Protestants exhibited during that era. Autocracy, in the view of these moderate Baptists, was buttressed by the Catholic Church in much the same way that democracy was furthered by Baptists. At the same event where Truett announced the decline of sacramentalism, the next speaker remarked, “This is a Baptist age because we are living in a world of expanding democracy.”9 (Interesting that these statements were made as the shadow of fascism was about to fall across Europe.) The idea that the advance of Baptist democracy is also the advance of American democracy, and vice versa, is still prominent within Southern Baptist moderate circles. Let me illustrate with an example from 1997, at a Baylor meeting of the Lilly Convocation of Church-Related Schools. Among the three speakers that day was James Dunn, at the time the executive director of the Baptist Joint Committee. Dunn lectured from his Southern Baptist moderate church-state separationist position, extolling soul freedom and the inviolability of individual rights. Over against these Baptist distinctives stood the Christian Right’s attempt to use the power of government to establish theocracy. One of those asked to give a response to the lectures was Notre Dame philosopher David Solomon, himself a former Texas Baptist. In critiquing Dunn’s lecture, Solomon said, “Of the three addresses we’ve heard today, James Dunn’s is the most vigorous defense of political liberalism.” Then Solomon said that if Dunn’s view of individualism and individual rights were to prevail in our culture, he feared there would be no more publicly spirited people such as Dunn. 12 Solomon’s critique was basically that Dunn had articulated no basis on which to build a sense of community that could sustain a conception of the common good, as well as form individuals who were imbued with a sense of public spiritedness. Dunn could not even account for the type of community that had formed him as he grew up in Amarillo as a Texas Baptist. What Solomon wanted to expose was that all Dunn had was liberal individualism, indeed the autonomy of the individual. In response Dunn said something to the effect that a good Christian is always a good citizen, which brought Baylor philosopher Scott Moore to the microphone to point out that such a statement was essentially Constantinian. The point I want to make is that Dunn was acting as the intellectual and spiritual son of Truett and Mullins. He was quite thoroughly confusing a Baptist sense of democratic polity, soul freedom, and religious liberty, with liberal notions of individual autonomy as formulated by John Rawls and others. Moreover, Dunn assumed that what was good for Christianity would always be good for civic life, hence a good Christian is always a good citizen. That Dunn would be like Truett and Mullins we would expect, but what we would not expect is that Dunn was also the intellectual and spiritual son of J. Frank Norris. Along with Truett and Mullins, Dunn assumed that the advance of American styled individual rights and democracy was the advance of the Baptist way. Along with Norris, Dunn assumed that a good Christian is always a good citizen. In Norris’s tirades against Catholicism then Communism he was a fundamentalist super-patriot, always blurring the line between the militant fundamentalist fight to save Christian orthodoxy, with the fight to save America from foreign influences. During the 1928 presidential campaign, Norris routinely warned that if Smith were elected, it would 13 be the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre of 1572 all over again, as Catholics would use the power of the state to make the nation Catholic much as the Catholic League tried to crush the Huguenots during the French Wars of Religion (1562-1596). For him, electing a Catholic was allowing the foreign enemy of Protestant America to gain a foothold in the U.S. government that would lead to disaster, almost like electing a Communist in 1948 or a member of Al Qaida today. Ironically, Norris’s anti-Catholicism put him in the same league with his arch-enemies Truett, Mullins, and many mainline Protestants who also spoke of Catholicism as un-American. Later, when the primary threat to America seemed to be communism, Norris assumed and preached that a good Christian would be an anti-communist, which was just another way of saying that a good Christian is always a good citizen. He became so anticommunist in the 1940s that when the pope was anti-communist, Norris stopped being anti-catholic. In an early version of culture war co-belligerency, he spoke highly of the Catholic Church as the “Gilbralter against communism in Europe,” and he even traveled to Rome, gaining an audience with Pope Pius XII. This pro-Catholic position gave him a new angle from which to attack moderate Southern Baptists who remained anti-Catholic but not anti-communist enough for Norris’s tastes. All this can get pretty confusing pretty fast, so let me pause and restate the argument thus far. The fundamentalist Norris and his moderate arch-enemies Truett and Mullins, and their intellectual and spiritual descendent Dunn, all took the same thing for granted. That thing was America’s liberal democracy, and more specifically individual freedom. That was the common good they all wished to defend and cultivate. Norris, Truett, and Mullins were thus anti-Catholic, then Norris came to view the communist 14 threat as so immense that he dropped his anti-Catholicism in favor of co-belligerency with the Pope. Moderate Southern Baptists, like most other Protestants, continued being anti-Catholic in their defense of the separation of church and state. Against the threats of Catholicism, Communism, or, in the case of Dunn, the Christian Right, all these Southern Baptists defended individual rights and democracy, which they believed were the sine qua non of Baptist history and the common good of American democracy. Let’s now push forward to the late twentieth-century and the Southern Baptist conservative evangelicals. In particular, let’s look at Richard Land, who I’ll use to illustrate the Southern Baptist conservative evangelical approach to the common good. Richard Land and the Conservative Evangelicals Like Norris, Land also grew up in Texas, in Houston. He then went to Princeton University for his undergraduate degree, New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary for his M.Div. and these very halls of Regents Park College, Oxford University for his doctorate in Baptist history. He seemed a prime candidate for a position at one of the moderate Southern Baptist Seminaries, but because of his own theological conservatism, and perhaps other factors more personal, he ended up identifying with the conservative or fundamentalist wing of Southern Baptist life. He landed at Criswell College in the mid1970s. Somewhere in his move outside southern and Southern Baptist culture, probably during his years at Princeton and Oxford, he encountered Francis Schaeffer and Carl F. H. Henry and began to identify with the larger evangelical world outside Southern Baptist life. As most of you know, when the conservatives took control of the SBC, Land was 15 named executive director of the denomination’s Christian Life Commission. Then, when the SBC defunded James Dunn and the Baptist Joint Committee, the Christian Life Commission took on religious liberty issues as well as ethical concerns, and changed its name to the Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission. Land has emerged over the past twenty years as one of the most visible and influential spokespersons of the Christian Right. While not quite as high profile as James Dobson, Land is nevertheless consulted by Republican Party leaders and even the president on a fairly regular basis. On the one hand, as I have argued elsewhere, Land and the SBC conservatives see themselves as being at war with the secularizing forces of democratic liberalism, which helps explain why they were so opposed to James Dunn and other moderates whom they believe side too strongly with the secular liberal emphasis on individual rights. Land and the conservative evangelical Southern Baptists also view American culture as being hostile to theistic positions of faith. This is true in one sense, but not in the way they think. There are secular liberal forces in American culture that oppose faith based comprehensive doctrines, but those hostile forces are not as representative of the whole culture as conservatives seem to believe. If those forces were so dominate, how could we explain Land moving prominently through the halls of Congress, appearing so regularly in the media, all the while fielding calls from the president and his people. While posturing as outsiders, Land and SBC conservatives are cultural insiders, at least within one of the armies fighting the culture wars. What is Land fighting for? If you want to know what Land believes on public issues these days, consult his most recent book, The Divided States of America: What Liberals and Conservatives are Missing in the God and Country Shouting Match. 16 Published by Thomas Nelson, the book is something of an answer to Jim Wallis’s God’s Politics: Why the Right Gets it Wrong and the Left Doesn’t Get It. These two evangelical culture warriors of the right and left both want to claim the vital center of American politics. Land critiques and rejects the Christian America view of many Christian Right activists and warns that such views can easily become idolatrous. At the same time, however, he argues along with Truett and Mullins, that [Quote] “The First Amendment is essentially the codification of the Baptist understanding of a free church and a free state.”10 Fortunately, Land need not contrast this great Baptist achievement with the views of Roman Catholics. Instead, he cites Vatican II’s Dignitatis Humanae as the Church’s proclamation of “the right of all to give public witness to their beliefs and to seek actively to persuade others to share them.” He even quotes extensively from the document and glosses his quote by writing “[T]he Vatican Council is basically affirming the Baptist viewpoint that the state must not use its power on behalf of itself, religion, or any other authority to impose on individual religious conscience.” 11 (So, Baptists wrote the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution and the Vatican II statement on religious liberty. There’s nothing quite like Baptist triumphalism.) Later, Land quotes Walter Shurden’s view that “Soul freedom is the historic Baptist affirmation of the inalienable right and responsibility of every person to deal with God without the imposition of creed, the interference of clergy, or the intervention of civil government.”12 Land then equates soul freedom with American religious liberty, and counts America’s soul freedom as part of American exceptionalism. “America’s uniqueness as a nation founded upon the concept of soul freedom is at the heart of why 17 this country is different from all others.”13 Land hardly differs from Truett and Mullins when he argues for the way in which Baptist views were written into the U.S. Constitution, and he uses this as a basis for his support of an activist American foreign policy based explicitly on American exceptionalism. Like George Bush, Land believes that because America has been uniquely blessed with abundance and with freedom, the nation has an obligation to foster freedom around the world. Land makes a brief effort to distinguish between soul freedom and the liberal view of individual autonomy when he writes, “Liberals’ most prominent value tends to be personal freedom. Their ultimate value is often individual autonomy. This is the fatal blind spot of the boomer generation: the presumption that they have the right to do whatever they please, whenever they want, with whomever they want, and nobody else has any right to judge them for it because it’s nobody’s business but theirs.”14 Land obviously believes there is a basis for judging the actions of others, and this does distinguish soul freedom from individual autonomy—somewhat. But me mentions the difference almost in passing. This is hardly a criticism, however, given that the moderates who have touted soul freedom so prominently in the past century have done so little to distinguish it from American freedom and democracy. Land believes his actions have consequences for others, and he quotes John Donne (not James Dunn) and the famous saying “no man is an island.” Beyond that, in a book about how Christians ought to be involved publicly, he doesn’t develop in theological detail how we should form our beliefs. But, to be fair, the problem isn’t just that Land has failed to locate an authority for spiritual formation outside the individual; the problem is that all Baptist thinkers combined over the past century have done so little to tell us how we are to form beliefs 18 and practices that differ in any significant way from the American notion that we are all free to make up our own minds about everything. I’ll bet that Land, like virtually all Baptist seminarians of his generation, read Axioms while in seminary. And it’s just as likely that at some point in his training some moderate suggested that, “Nobody but Jesus gonna tell me what to believe.” The progressive dissenters I’ll say much less about the progressive dissenters than the others, and, as I said at the beginning today, I’ll be following largely David Stricklin’s book A Genealogy of Dissent. Notice that thus far we have Norris who began his career as an insider then chose to become an outside dissenter on the right; Land started as a right-wing outsider— a dissenter on the right—then became an insider when his group took control of the SBC; and Truett and Mullins, who were ever the quintessential insiders. Stricklin’s dissenters were left-wing outsiders. Existing on the fringes of Southern Baptist life, they chose intentionally the posture of the prophet. Unlike the conservative dissenters such as Land, they harbored no desire to take over the denomination and wouldn’t have known what to do with it if they had. One can argue that in the pre-civil rights South in which the dissenters were reared and trained, churches were bound together by accidents of race, class, and custom. Charles Marsh makes this point in God’s Long Summer in a chapter on First Baptist, 19 Jackson’s pastor Douglas Hudgins. Marsh traces this defective conception of the church directly to Mullins’s theology of soul competency. Hudgins was in many ways the typical big-city Southern Baptist pastor. In the face of the violence against Civil Rights workers in the early sixties, he argued that the gospel had nothing to do with social or political questions because the gospel dealt only with individuals and their direct experiences with God. Even when the local Jewish rabbi pled with Hudgins to speak out against the bombing of the Jackson synagogue, Hudgins refused to intervene. When the rabbi’s home was bombed a few weeks later, Hudgins finally made a passing remark that no one should bomb another man’s home (duh), just before launching into his exposition of a scriptural text—one that no doubt related to an individual’s relationship to Jesus. Soul competency for Hudgins meant that each individual had to deal directly with God with no intermediary, the corollary of which was that there was no corporate expression of community beyond the church as a collection of transformed individuals bringing together their solitary encounters with God.15 And what will hold these individuals together in Christian community? As Marsh puts the case, all that is left are race, class, and custom around which to form some a sense of community. There can be no mystical “body of Christ,” or any other theologically thick community. Marsh alludes to Harold Bloom’s critique of Mullins. In his book The American Religion, Bloom interprets Mullins’s theology as meaning that the interiority of the solitary encounter with God precedes all other forms of authority, certainly that of the church, and perhaps even the authority of scripture.16 20 Stricklin makes it clear that in some ways white Southern Baptist dissenters such as Walter Nathan Johnson and those he influenced, especially Martin England and Clarence Jordan, attempted to develop a conception of the church that had been missing in typical Southern Baptist congregations such as First Baptist, Jackson. Johnson, England, and Jordan argued precisely this point: that the typical Southern Baptist had a defective understanding of Christian community. England characterized Johnson as being obsessed with the way that Baptist churches “had missed the mark on what it meant to be church [because a] class church . . . of only well-to-do people . . . was a denial of the basic spirit and teachings of Jesus.”17 That was England paraphrasing Johnson. England and Jordan attempted to develop a Christian community that would be a living witness against segregation, discrimination, and, perhaps most importantly, against the typical Baptist church that was based on race, class, and custom. I want to suggest that there was a sense in which Stricklin’s dissidents were working against the common good—at least as it was understood at the time. The South, as we all know, was an organic, hierarchical society based on race, class, and custom. Everyone benefited by learning his or her place and staying in it. The common good was the maintenance of this organic society. One thinks of the film footage of Governor George Wallace in an automobile heading to the University of Alabama in 1964 to try to stop the integration of the university. As he rides to his destiny with history, the camera catches him muttering, “Segregation’s just as good for the blacks as it is the whites.” “Sweet Home Alabama, where the skies are blue, and the governor’s true.” There are countless examples. 21 This organic hierarchy of race, class, and custom provided southern society with its peace and stability. The dissidents were met with violent resistance precisely because the message of the Civil Rights movement, the message that segregation was sinful and had to go, directly threatened the very fabric of southern life. The churches were part of that fabric. They were, in fact, not much more than voluntary societies dedicated to the preservation of what held southern culture together. Southern Baptist dissidents who insisted on racial integration within the community of Christ and within the larger social community were working against the common good as commonly understood by white southerners. In this sense, they were Christian, but they were not good citizens. One of the interesting dynamics that Stricklin covers is the tension and even hostility between Christian Life Commission executive director Foy Valentine and the dissidents. Valentine was a product of the dissident network, having been heavily influenced by Clarence Jordon. Valentine chose the path of the prophetic insider, however, attempting to steer the denomination in the direction of racial integration. Part of Valentine’s critique of the dissidents was: First, that they were ineffective dreamers who really didn’t care if they were ever successful in changing the denomination. Second, he accused them of not having paid their dues within the SBC. He contrasted the dissidents to fellow insider T.B. Maston, the renowned ethicist at Southwestern Seminary. Maston, Valentine argued, had paid the price by attending prayer meetings, writing denominational Training Union guides, and so forth. He was a denominational loyalist and therefore carried authority among Southern Baptists. The dissidents, by contrast, could be easily dismissed as outsiders no one needed to listen to. Third, 22 Valentine criticized the dissidents for being enamored with the North, where many of them had received their education. What I want to point out is that the standard that Valentine applied to the dissidents was the effectiveness or success standard. They could not effectively or successfully influence the denomination because they were outsiders—outsiders to their denomination, and, as illustrated by Valentine’s charge that they were enamored with the North, outsiders to their larger culture. This is a telling criticism—not of the dissidents, but of Valentine. The idea of being an outsider—that is being separate from the culture—would seem a biblical prerequisite for the church. Moreover, the standard for the church is faithfulness, not effectiveness or success. Even effectiveness in moving one’s culture toward a common good that would include all people, not just whites, is secondary to faithfulness to Christ. I don’t know enough about Clarence Jordon to make definitive statements, but it seems that at Koinonia Farms, folks cared a good bit less than Valentine whether they were being effective or successful in reshaping the culture. If I’ve read the situation correctly, they were trying to live out the gospel in faithful community, in part to stand as a witness for Christ. A happy byproduct may have been that they helped reshape the southern notion of the common good, but I don’t think this was their primary goal. It may well be that promoting the common good is like happiness—best accomplished when that is NOT what one is seeking, but is rather a byproduct of living as dissenters from the commonly understood common good, faithful to the gospel’s call to be the church. As I said at the beginning, I began working on this address thinking it likely that all four types of Baptists I’m identifying sought to foster some notion of the common 23 good. I’m willing to concede now that there may have been a difference between the first three types who pretty thoroughly confused Baptist identity with cultural and even national ways, at least at some points, and Stricklin’s dissenters who may have gotten closer to a conception of Christian community that was distinct from cultural definitions of the common good. (Did I mention there was suppose to be a question mark at the end of my title? Printer problem, I suppose) Still, however, I wonder if we tracked Stricklin’s genealogy forward to some of the most progressive Southern Baptist churches today we would find that they moved from Civil Rights to women’s rights to gay rights with such a straight line trajectory and so little consideration of theology that it seems likely that faithfulness as a community of believers has been superseded by a commitment to the rights of individuals as solitary dissenters. Sound familiar?? The echo of Truett and Mullins?? In short, a community bound together by race, class, and custom, has been replaced by a community held together by underdeveloped notions of dissent, the result being that culture is still calling the shots. If traditional culture does one thing, the dissenters do the opposite, or perhaps if progressive culture goes one direction, the dissidents go with it in order to dissent against the Southern Baptist traditionalists, who are then characterized as being bound by culture. This tendency to let the culture define where one stands is in many ways similar to the SBC conservative evangelicals who, being as they are uneasy in Babylon (huh, huh), almost instinctively do the opposite of what they see as the secular cultural norm. Perhaps what we’re seeing here is a perennial tendency in Christian history to either dominate the culture and live triumphally within it, or if that is not possible to develop a sub-culture of dissent and live triumphally there. In either case there seems a 24 powerful temptation to create a common good—dominant or dissenter—then serve that common good by allowing the accidents of the culture to be the stuff of community. At this point in my life, I’ve come to believe that this difficulty in resisting the temptation to create a culture or subculture and live triumphally in it, is a perennial problem that we will never overcome. It is THE struggle for all who attempt to be the church. A New Baptist Covenant The looming Baptist Covenant is a good example of what happens when a people travels down the road of closely identifying the ways of God (or at least Baptist history) with the ways of their culture. The Baptist Covenant, of course, is not organized along lines of race, class, and custom. Rather, it is organized around the opposites of these cultural accidents. The themes of the plenary sessions for the January 2008 meeting are: Unity in Seeking Peace with Justice; Unity in Bringing Good News to the Poor; Unity in Respecting Diversity; Unity in Welcoming the Stranger; Unity in Setting the Captive Free. One wonders if this so-called Baptist Covenant convocation—meeting as it is on the eve of the New Hampshire Primary—is political, not theological or even ecclesiological. How easily will “Unity in seeking peace with justice” be translated into opposition to the War in Iraq; “Unity in Bringing good news to the poor” translated into support for government programs for those in poverty; “Unity in respecting diversity” translated into support for a particular understanding of the separation of church and state; “Unity in welcoming the stranger” translated into particular positions on immigration; and “unity in setting the captive free” into—I really have no idea, but I if 25 this were a Christian Right gathering “unity inn stetting the captive free” would, no doubt, mean freeing the Iraqi people from Saddam Hussein. These are all good causes, and politically I’m pretty much in step with those who will meet in the Baptist Covenant meeting in January. Still, it seems to me a real sign of trouble when a denomination of Christians can no longer rally together around biblical or theological notions such as a triune God as manifest uniquely in the person of Jesus Christ, experienced through salvation by faith, and baptism into the body of believers that becomes the transcendent as well as earthly alternative to all other ways of organizing ourselves as human beings. It seems a clear sign of theological impoverishment when the accidents of politics are what we really have in common as REAL Baptists, as opposed to those other Baptists of the Christian Right. Although the themes of the Baptist Covenant meeting in January are biblical on their face, I’m suggesting that given the history I’ve outlined today, those concerns will become particular political and cultural positions pretty easily. In short, it will take a heroic effort for the leaders to keep the meeting nonpolitical, let alone non-partisan. This is especially so because the lead figures, Jimmy Carter and Bill Clinton, are active and vocal partisans of the Democratic Party. If the leaders cannot succeed in this nearly impossible task, the Baptist Covenant will be little more than an alternative to the politics of the Christian Right and the Southern Baptist Convention. Conclusion 26 In short, and in conclusion, the Southern Baptist habit of identifying Baptist democracy and liberal democracy dies hard when there is an overdeveloped tendency to see a social problem and act and an underdeveloped notion of resisting the activist tendency in order to carefully consider the deeper theological basis for how we practice community and relate to the culture around us. Noll said that “the tendency of evangelicals when they see a problem is to act; for the sake of the evangelical mind, that tendency must be suppressed.” I’m suggesting that the tendency of Southern Baptists in the twentieth century was to promote the common good of American or southern culture, or to develop a dissenter culture and then promote its good. For the sake of Baptist identity this tendency to build and promote cultural concerns by touting individualism, democracy, freedom, and dissent should be suppressed and then superseded by a deeper contemplation of what it means to be the church, and even more by Christian practices carried out in a community of worship. 1 Mark Noll, The Scandal of the Evangelical Mind (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans, 1994), 243. Canipe, 233; George Truett, “God’s Call to America,” in God’s Call to America (New Y ork: George H. Doran Company, 1923), 19. 3 Canipe, 233-34 and 237; George Truett, “The Prayer Jesus Refused to Pray,” in Follow Thou Me (Nashville: The Sunday School Boar of the Southern Baptist Convention, 1032), 43. 4 Canipe, 244; George Truett, “Baptist and Religious Liberty,” reprinted in Baptist History and Heritage 33 (Winter 1998), 82. 5 Canipe, 191; E.Y. Mullins, “ Baptists in the Modern World,” Review and Expositor 8 (1911): 348. 6 Canipe, 203-206; E. Y. Mullins, The Axioms of Religion, 185. 7 Canipe, 207; Mullins, The Axioms of the Christian Religion, (Philadelphia: Judson Press, 1908), 207. 8 Canipe, 208; Mullins, Axioms, 255. 9 Canipe, 176. 10 Richard Land, The Divided States of America (Nashville, Tennessee: Thomas Nelson, 2007), 125. 11 Land, 125. 12 Quoted in Land, 214. 13 Land 216. 2 27 14 Land, 230. Charles Marsh, God’s Long Summer: Stories of Faith and Civil Rights (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1997), 109. 16 Marsh, 110; See Harold Bloom, The American Religion: The Emergence of the Post-Christian Nation (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1992). 17 England characterizing Johnson as quoted in David Stricklin, A Genealogy of Dissent: Southern Baptist Protest in the Century (Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 1999), 57. 15