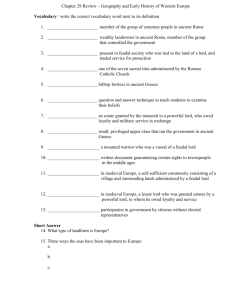

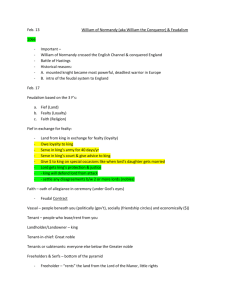

JanetWGrade10MedievalSociety

advertisement

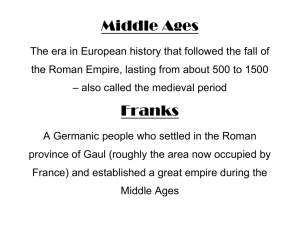

Methods in Teaching History Janet Warzecha History Project -Document Based Questions (DBQ) Interpreting the Feudal Structure of Medieval Society in Europe Curriculum source Grade 10: Ancient Medieval History (1997) World History Unit 5: The Middle Ages: Collapse and Recovery Outcome 4: Identify the essential elements of medieval feudalism and manorialism (p.41) Background Information: In Unit 5, students will learn that it is generally accepted that the medieval period began after the collapse of Rome in 5th century and continued until the 15th century. Although Feudalism was not a uniform system in its application, it was prevalent and whatever complex form it took, it influenced the societal and political relationships of most people in Europe. The system was based on loyalty and the holding of land and the land represented wealth and power. Feudalism offered a measure of stability to Europe especially as compared to the aftermath of the collapse of the Roman Empire. Feudalism would persist in different forms for over one thousand years. Setting: Three major classes of people emerged in feudal society in the medieval period. They included the nobility, the clergy, and the peasants. Each of these classes had hierarchies, rules, traditions, obligations and expectations that the members were bound to follow. Each class had a general role and responsibility and each class was dependent on the other class to function within the agreed social and political boundaries. The interdependence of the feudal classes allowed the system to operate provided a general stabilizing effect in Europe. However, there were also costs and negative features of feudalism which would contribute to its downfall and these would help to change the institutions and nations of Europe. Source: http://www.mnsu.edu/emuseum/history/middleages/feudal.html Project: In this DBQ project, students will examine medieval society in Europe and the feudal classes that developed after the collapse of Rome. Students will learn more about why the various classes developed and how they interacted in feudal society. The DBQ sources will assist the student in gaining a much deeper insight of feudal society in Medieval Europe and the reasons why the feudal society developed as it did. Several documents will cause the students to carefully consider certain practices of that period and their moral or ethical acceptability in comparison to today’s society. Also, through the investigation of the bonus question document, the students should begin to see historic connections to practical and ceremonial functions that continue to exist in Canadian society today such as in its parliament and laws. 1 Investigation: The Medieval Period is referred to as the Middle Ages Period and sometimes as the Dark Ages. Answering the following key questions will assist in a better understanding of this period in history and why these terms and others might have been used to describe this period. There are also questions given with each source to prompt thinking about the source information. 1. Describe the three basic classes of feudal society and their general roles and responsibilities. How did the three classes cooperate to provide stability within feudal society? 2. What can we learn about feudal society from the structures including the castle, the church, and the manor and how would living within these structure shape the thinking of the people? 3. Why did the three classes continue to cooperate and sustain feudal society? What examples show the kinds of thinking and controls that were in place to ensure cooperation? Were these justifiable? Is the term ‘Dark Ages’ the best term to describe this period and why? 4. Bonus Question: Are there any traces of Medieval Feudalism that can still be found in Canadian society today? (See last sources) 2 DBQ Sources: Source 1 There were major forces that acted on Western Europe that changed its political and social structures in the Middle-Ages. What general structure and organization emerged in Europe? Why did the major social groups that emerged become interdependent and together were generally self-sufficient? From 600 to about 900, Europe seemed to have been trying to reconstruct the old Roman Empire of the West. The Church, which had become a branch of the Roman imperial government in the course of the 300's, survived the collapse of the political and military of the Roman Empire in the West. It tried to preserve Roman imperial institutions and principles to the point where local bishops often took over the authority and regalia of the old Roman provincial governors. It was in the cathedrals and monasteries of the West that Roman learning was preserved to the extent that it was in fact preserved. As influential as the Church might have been however, it needed power to pursue its apparent goal of restoring the Roman Empire. […]The efforts were finally successful in the year 800, when the Frankish king, Charles, was crowned as Holy Roman Emperor on Christmas Day. The rulers of Western Europe could at least claim that they had restored an independent Roman Empire of the West, although the new empire was only superficially like even the actual Roman Empire. Nevertheless, the reign of Charles the Great, usually called Charlemagne (768- 814), represented a considerable recovery, and is often regarded as a renaissance, or "rebirth" of Roman culture, by historians. This happy situation did not last long. The Franks had the interesting custom of dividing their estates equally among all of their children. So Frankish kings would divide their kingdoms among their sons; the sons would soon be embroiled in a civil war until one of them won out over the others and reunified the king; and then he would die and the kingdom would be divided among his sons. Charlemagne had been lucky that his brother had decided to abdicate and enter a monastery, and all of Charlemagne's sons except Louis, his youngest, died before their father. […]While Louis' sons were fighting among themselves, Western Europe was attacked from all sides by a new wave of invaders, although these invaders tended to raid and plunder more than conquer and settle. From Scandinavia came the Vikings, sailing up and down the coasts of Europe and up its rivers deep into its interior. They were pagans, fierce warriors, and quite bloody- minded. For many years, it was common enough for priests to end their prayers with the words ... and from the fury of the Northmen, Good Lord, protect us. Amen. There were also new invaders from central Asia, people calling themselves Magyars, but called Huns by the inhabitants of Western Europe. Riding swift ponies, they raided much of German, France and northern Italy. Finally, the western Mediterranean Sea was dominated by the Saracens, inhabitants of the North African coast who had converted to the new (since 622) religion of Islam. […]The nature of these hit-and-run attacks was such that no central government could respond effectively, even if the rulers of the central governments had not been engrossed in fighting each other. Local strong men built fortresses that offered protection to the peasants in their locality, and these local "bosses" took military and political power into their own hands. The Kingdom of Germany 3 disintegrated into a half dozen small states, while France collapsed into something close to anarchy, with literally hundreds of local barons each controlling the territory and the people around their castles. From about 900 to about 1000, Europe was fighting for its very existence and, in the course of that struggle, developed new institutions and values that owed relatively little to the old Roman Empire. The local rulers of the time were too busy to engage in dreams of centralizing authority in a revived Roman Empire and were generally content to adopt whatever seemed to work. Europe emerged from that period with a society based upon three basic institutions. One was the local ruler who exercised governmental powers, protected his people with a castle in which they could take refuge in time of need, and defended them clad in armor and riding to battle mounted on a war-horse. The second was the churchman, either priest or monk, who represented a Church that was no longer interested in functioning as a branch of an imperial government, but sought to be independent of secular authority and to set the moral and ethical standards for Europe. The third was the peasant, organized into village communities that functioned as agricultural cooperatives, sharing the tasks of plowing and regarding the surrounding meadows and forests as a common possession. Each of these supported the other in important and even essential ways and, together, they were able to produce a sufficient surplus of food to support a great number of warriors. http://vlib.iue.it/carrie/reference/worldhistory/sections/13europe.html This text was produced and installed by Lynn H. Nelson, Department of History, University of Kansas. Source 2 This poem translated from an 11th Century bishop outlines his view of the medieval world. What does this poem tell us about the main classes of people? What does this poem suggest about this order in society? Those Who Pray, Work, and Fight It is well known that in this world there are three orders, set in unity: these are laboratores, oratores, bellatores. Laboratores are those who labor for our living; Oratores are those who plead for our peace with God; Bellatores are those who battle to protect our towns and defend our land against an invading army. Now the farmer works to provide our food, And the worldly warrior must fight against our foes, and the servant of God must always pray for us and fight spiritually against invisible foes… Adalbero, bishop of Laon, Poem for King Robert, c.1025; edited by C. Carozzi http://lib.colostate.edu/research/history/medievalhist.html 4 Source 3 An official public ceremony was part of making the agreement between a vassal and a noble and rarely there was a written record. This is a copy of one of a rare English record. Why do you think these ceremonies were public? Why was there not usually a written record made? What level of loyalty did the vassal promise to his lord? Thus shall one take the oath of fidelity: By the Lord before whom this sanctuary is holy, I will to N. be true and faithful, and love all which he loves and shun all which he shuns, according to the laws of God and the order of the world. Nor will I ever with will or action, through word or deed, do anything which is unpleasing to him, on condition that he will hold to me as I shall deserve it, and that he will perform everything as it was in our agreement when I submitted myself to him and chose his will. An Anglo Saxon Form of Commendation [from Schmidt: Gesetze der Angelsachsen, p. 404] http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/source/feud-oath1.html Source 4 The following diagram illustrates a pyramid which shows the different classes and their positions in the feudal society. What does this pyramid structure suggest about the people that are represented in each group? Walker, Robert J. Prologue to the Present Ancient and Medieval Civilizations Toronto: Oxford, 1997. p. 302, Figure 11-8 5 Source 5 In this document, a vassal with major land holdings is pledging his loyalty to a greater lord. What is there that is significant about the person who receives the homage? What is significant about the wording of the oaths? Why was such wording used and what did it indicate about the loyalty of the vassal? Right of Homage and Fealty, 1110 In the name of the Lord, I, Bernard Atton, Viscount of Carcassonne, in the presence of my sons, Roger and Trencavel, and of Peter Roger of Barbazan, and William Hugo, and Raymond Mantellini, and Peter de Vietry, nobles, and of many other honorable men, who have come to the monastery of St. Mary of Grasse, to the honor of the festival of the august St. Mary: since lord Leo, abbot of the said monastery, has asked me, in the presence of all those above mentioned, to acknowledge to him the fealty and homage for the castles, manors, and places which the patrons, my ancestors, held from him and his predecessors and from the said monastery as a fief, and which I ought to hold as they held, I have made to the lord abbot Leo acknowledgment and homage as I ought to do. Therefore, let all present and to come know that I the said Bernard Atton, lord and viscount of Carcassonne, acknowledge verily to thee my lord Leo, by the grace of God, abbot of St. Mary of Grasse, and to thy successors that I hold and ought to hold as a fief in Carcassonne […] and I swear upon these four gospels of God that I will always be a faithful vassal to thee and to thy successors and to St. Mary of Grasse in all things in which a vassal is required to be faithful to his lord, and I will defend thee, my lord, and all thy successors, and the said monastery and the monks present and to come and the castles and manors and all your men and their possessions against all malefactors and invaders, at my request and that of my successors at my own cost; and I will give to thee power over all the castles and manors above described, in peace and in war, whenever they shall be claimed by thee or by thy successors. Moreover I acknowledge that, as a recognition of the above fiefs, I and my successors ought to come to the said monastery, at our own expense, as often as a new abbot shall have been made, and there do homage and return to him the power over all the fiefs described above. And when the abbot shall mount his horse I and my heirs, viscounts of Carc assonne, and our successors ought to hold the stirrup for the honor of the dominion of St. Mary of Grasse; and to him and all who come with him, to as many as two hundred beasts, we should make the abbot's purveyance in the borough of St. Michael of Carcassonne, the first time he enters Carcassonne, with the best fish and meat and with eggs and cheese, honorably according to his will, and pay the expense of shoeing of the horses, and for straw and fodder as the season shall require. And if I or my sons or their successors do not observe to thee or to thy successors each and all the things declared above, and should come against these things, we wish that all the aforesaid fiefs should by that very fact be handed over to thee and to the said monastery of St. Mary of Grasse and to thy successors.... Made in the year of the Incarnation of the Lord 1110, in the reign of Louis. 6 From Teulet: Layetters du Tresor des Chartres No. 39, Vol 1., p. 36, translated by E.P. Cheyney in University of Pennsylvania Translations and Reprints, (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1898), Vol 4:, no, 3, pp. 18-20 http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/source/atton1.html Source 6 The feudal contract provided for several practical benefits for the lord and the vassal. According to this source, what were some of these? Since there were no written laws to protect these contracts, how could the participants be certain that they would be honoured? (FEUDAL AGREEMENT) It would be easy to deduce all forms of political organisation and of social intercourse from feudal contract. The status of a person depended in every way on his position on the land, and on the other hand, land-tenure determined political rights and duties… The acts constituting the feudal contract were called homagium and investitures. The tenant had to appear in person before the lord surrounded by his court, to kneel before him and to put his folded bands into the hand of the lord, saying: "I swear to be faithful and attached to you as a man should be to his lord." He added sometimes: "I will do so as long as I am your man and as I hold your land" (Saxon Lehnrecht, ch. 3). To this act of homage corresponded the "investiture" by the lord, who delivered to his vassal a flag, a staff, a charter or some other symbol of the property conceded… Tenure conditioned by service was called the feudum, fief…. The holdings… were deemed in law to be at the will of the lord, but in practice were protected by the local custom and generally subjected to quasi-legal rules of possession and inheritance. Although feudal tenure was certainly the most common mode of holding land, it was not the only one. The dangers of keeping outside the feudal nexus were self-evident: in a time of fierce struggles for bare existence it was necessary for everyone to look about for support, and the protection of the central authority in the State was, even at its best, not sufficient to provide for the needs of individuals. Even in England, where the Conquest had given rise to a royal power possessed of very real authority, and the "king's peace" was by no means a mere word, the maintenance afforded by powerful lords was an important factor in obtaining security. In any case the feudal nexus originated by such conditions involved reciprocity. The vassal expected gifts and at least efficient protection, and sometimes the duty of the suzerain in this respect is insisted on in as many words… The other side of the medal is presented by the duties of vassals in regard to the lord. Close analysis shews that these duties proceed from different sources. There is to begin with a general obligation of fealty, faithful obedience (fidelitas)which is owed by all subjects of the lord without distinction of rank… fealty became a relation between private lords and their subjects… Homage again, which is distinctly contractual, arises essentially from a contract of service. It proceeds directly from the bond created by free agreement between a leader and a follower, the lord (hlaford) and his man… The negative duties of the faithful vassal are indicated by the following terms: incolume, tutum, honestum, utile, facile, possible…the vassal undertakes not to assail his lord, not to reveal his secret, not to endanger the safety of his castles, not to wrong him in his judicial power, honours and 7 possessions or to put obstacles in his way which would render what he undertakes difficult or impossible. On the positive side the vassal is bound to give his lord advice and aid (consilium, auxilium). http://socserv2.socsci.mcmaster.ca/~econ/ugcm/3113/vinogradoff/feudal Source 7 This is a map of Feudal Europe in 1300. What does it suggest about the political control during this time period? http://www.euratlas.com/big/europe_map_1300.html#%20here 8 Source 8 The manor was the community that was home to most people in the Middle Ages. According to this source, what did the community provide to its people? What kind of life did most people lead? Was there a relationship between the different classes and what was it? Did one part of the community receive more of the benefits? ( MANOR ) The manor is a necessary outcome of so-called natural husbandry, providing for the requirements of life by work carried out on the spot, without much exchanging and buying. It is the connecting link in the social life of classes, some of which are primarily occupied with the rough work of feeding, clothing and housing society, while others specialise in defending it and providing for its secular and spiritual government. It presents the lowest and most efficient unit of medieval organisation, and local justice, administration and police are all more or less dependent on its arrangements. Let us look at the different elements of which this historical group is composed. First of all there is the economic element. The manor afforded the most convenient, and even the necessary, arrangements of work and profit in those times. It would be quite wrong to assume that the interests and rights of the many were simply sacrificed to the interests and rights of a few rulers, that the manor was nothing but an estate, cultivated and exploited for the sake of the lord and managed at discretion by his will and the will of his servants. On the contrary, one of the best established facts in the economic life of the manor was its double mechanism, if one may say so. It consisted, as a rule, of a village community with wide though peculiar self-government and of a manorial administration superimposed on it, influencing and modifying the life of the community but not creating it. This double aim and double mechanism of the manor must be noticed at the outset as a very characteristic feature; it places the manor in a sharp contrast both to the plantations of slaves of the ancient world and to the commercial husbandry of a modern estate struggling for profit as best it may. Manorial husbandry was all along striving towards two intimately connected aims, providing the villagers with means of existence and providing the lord with profits. Hence a dual machinery to attain these aims, both a village community and the lord's demesne. http://socserv2.socsci.mcmaster.ca/~econ/ugcm/3113/vinogradoff/feudal Source 9 This story provides insights into a medieval monastery. What does this story tell about the authority of the leadership and the loyalty of the followers? Was there justice done in this story? What unusual event was claimed to take place and what do you think about the claim? The Abbot of the monastery wrote this story. In time, he would become Pope Gregory I. How might this and other experiences condition his thinking when he became the head of the Roman Church? The Consequences of Breaking the Rules "There was in my monastery a certain monk, Justus by name, skilled in medicinal arts. . . When he knew that his end was at hand, he made known to Copiosus, his brother in the flesh, how that he had three gold pieces hidden away. Copiosus, of course, could not conceal this from the brethren. He sought carefully, and examined all his brother's drugs, until he found the three gold pieces hidden away among the medicines. When he told me 9 this great calamity that concerned a brother who had lived in common with us, I could hardly hear it with calmness. For the rule of our monastery was always that the brothers should live in common and own nothing individually. Then, stricken with great grief, I began to think what I could do to cleanse the dying man, and how I should make his sins a warning to the living brethren. Accordingly, having summoned Pretiosus, the superintendent of the monastery, I commanded him to see that none of the brothers visited the dying man, who was not to hear any words of consolation. If in the hour of death he asked for the brethren, then his own brother in the flesh was to tell him how he was hated by the brethren because he had concealed money; so that at death remorse for his guilt might pierce his heart and cleanse him from the sin he had committed. When he was dead his body was not placed with the bodies of the brethren, but a grave was dug in the dung pit, and his body was flung down into it, and the three pieces of gold he had left were cast upon him, while all together cried, 'Thy money perish with thee ! ' . . When thirty days had passed after his death, my heart began to have compassion on my dead brother, and to ponder prayers with deep grief, and to seek what remedy there might be for him. Then I called before me Pretiosus, superintendent of the monastery, and said sadly: 'It is a long time that our brother who died has been tormented by fire, and we ought to have charity toward him, and aid him so far as we can, that he may be delivered. Go, therefore, and for thirty successive days from this day offer sacrifices for him. See to it that no day is allowed to pass on which the salvation-bringing mass [hostia] is not offered up for his absolution.' He departed forthwith and obeyed my words. We, however, were busy with other things, and did not count the days as they rolled by. But Io ! the brother who had died appeared by night to a certain brother, even to Copiosus, his brother in the flesh. When Copiosus saw him he asked him, saying, 'What is it, brother? How art thou?' To which he answered: 'Up to this time I have been in torment; but now all is well with me, because today I have received the communion.' This Copiosus straightway reported to the brethren in the monastery. Then the brethren carefully reckoned the days, and it was the very day on which the thirtieth oblation was made for him. Copiosus did not know what the brethren were doing for his dead brother, and the brethren did not know that Copiosus had seen him; yet at one and the same time he learned what they had done and they learned what he bad seen, and the vision and the sacrifice harmonized. So the fact was plainly shown forth how that the brother who had died had escaped punishment through the salvation-giving mass." http://www.eyewitnesstohistory.com/pfmonastery.htm 10 Source 10 The word peasant has commonly accepted implications. What is surprising about this account about peasants? What is not surprising? Why? Roles and Rights of a Peasant Three different groups of peasants might live on the manor. Slaves, who could be bought and sold, existed, but their number declined after the early Middle Ages. Serfs, would could neither leave the manor nor be forced to go, made up the majority of peasants. Freemen, who owned small pieces of land and could move about freely, were a small portion of the society until the rise of towns. Although the contrast in status and living conditions between lord and peasant was great, each had certain rights according to the custom of the manner. The lord needed grain for the castle’s storehouse, and any unjust treatment might result in a decline in production. Also a runaway serf was hard to replace. Justice had to be enforced in open court. A peasant could not refuse to work, and the lord could not evict him, so they respected each other’s rights. A serf had no political rights; he was bound to the soil. A serf who could escape might locate in a town which offered opportunities for the skilled craftsman. If he remained free for one year and one day, he became a freeman. Other peasants escaped their burdens by taking up a career in the Church. The hard daily life was balanced for those who remained on the land by the security of the land and work, coupled with knowing that their children would be cared for if anything happened to them. A serf was valuable to the landowner primarily because of the work he could do and the fees that he could pay. The peasants paid taxes in the form of products or in coin when it became common. Fees were collected by the lord on a number of occasions, such as when a daughter married off of the manor, when a son inherited his father’s land, or when peasants used the lord’s oven, winepress, or mill. There were fees paid for marriages, at death and, of course, to the Church. Besides working on the lord’s land, usually three days a week, the peasants were expected to do repair work around the manor on roads and bridges. They were excused from military service except in time of siege. Most peasants were “jacks of all trades”; besides farming, they fixed their tools and made their own clothes and shoes. There were some who specialized, such as blacksmiths, wheelwrights, carpenters, tanners, and bakers. Most worked the land, but some peasants were shepherds. All worked from the necessity to survive; the workday was long, but everyday activities were varied, and numerous holidays existed for recreation. The peasants’ lot was cast in the medieval world; they were simply the work force. As the Middle Ages wore on, the most intelligent, ambitious, or luckiest peasants became the craftsmen, traders, and merchants of the early towns. http://www.cis.yale.edu/ynhti/curriculum/units/1986/3/86.03.03.x.html) 11 Source 11 Why was the church so important to medieval society? How could the significant difference in the wealth between the pope and the lowest of the clergy be justified during the medieval period? The Roman Catholic Church was the single, largest unifying structure in medieval Europe. It touched everyone's life, no matter what their rank or class or where they lived. With the exception of a small number of Jews, everyone in Europe was a Christian during the Middle Ages from the richest king down to the lowest serf. From the moment of its baptism a few days after birth, a child entered into a life of service to God and God's Church. As a child grew, it would be taught basic prayers, would go to church every week barring illness, and would learn of its responsibilities to the Church. Every person was required to live by the Church's laws and to pay heavy taxes to support the Church. In return for this, they were shown the way to everlasting life and happiness after lives that were often short and hard. In addition to collecting taxes, the Church also accepted gifts of all kinds from individuals who wanted special favors or wanted to be certain of a place in heaven. These gifts included land, flocks, crops, and even serfs. This allowed the Church to become very powerful, and it often used this power to influence kings to do as it wanted. The Pope The head of the Church was called the Pope. As God's representative on Earth, the Pope had a great amount of power to influence kings and their advisors. If someone went against the Church, the Pope had the power to excommunicate them. This meant that the person could not attend any church services or receive the sacraments and would go straight to hell when they died. At a time when everyone believed in heaven and hell and all belonged to the Church, this was an awful punishment. Under the Pope, were his bishops who ruled the lower classes of priest in the same manner that an earl would rule his vassals. The Parish Church The parish church was the center of every town. It was generally the largest building in town and had stained glass windows and statues that told stories from the Bible to the villagers who, for the most part, could not read. This building and the religion it stood for were involved in every aspect of the lives of the people. A newborn infant would be baptized here and enter into a union with God. A couple would exchange their wedding vows before God in this church. When a person died, the final prayers would be said there and the body would be buried in ground that had been consecrated by the Church. If crops failed or someone fell ill, people would come to the church to pray to God for help. Every Sunday, every villager went to church to a service in Latin (which they didn't understand) and a sermon (which they did understand). On Holy Days, when the Church forbade them to work, the people came to give praise to God for the good things in their 12 lives. The parish church was overseen by a parish priest, whose duties were to teach the Christian gospel to his parishioners, and help them to live their lives by God's laws. Pilgrimages Pilgrimages were journeys made to places that held special religious significance. Usually, this was a shrine where a saint was buried or a visit to the Holy Land itself. Making a pilgrimage was long and often dangerous. Almost everyone traveled on foot and bandits and pirates lay in wait for the unarmed pilgrims. However, people went on these journeys anyways because they felt that prayers made at a saint's tomb were especially powerful. If a loved one fell ill, a relative might promise to make a pilgrimage if the person got better, or someone might go to show that they were sorry for their sins. Monks and Nuns Because religion was so important during the Middle Ages, many people devoted their whole lives to being closer to God and doing the Church's work. Sometimes, parents promised their children to this religious life in order to fulfill a promise to God and to ensure their children were never homeless or without food. These people became monks (if they were men) or nuns (if they were women) and lived apart from the rest of the people in special communities called monasteries and nunneries. Monks and nuns promised to always remain single, to be obedient to their superiors and to live a life of prayer. They ate simple food, dressed in simple clothes (called habits) and spent their days in silence, praying or working. They also attended many church services. There were seven main church services each day, the first at dawn and the last in the middle of the night. http://www.mnsu.edu/emuseum/history/middleages/church.html Source 12 Why were castles built and how did the nobility use them? This decentralisation of land-holding and power required that each landholder provide himself with a base from which to operate. This base should also be designed to afford protection to himself, his family and all those who lived on and worked his lands. The great magnates and many of the lesser barons would hold lands in different parts of the kingdom and require several bases. The landholdings of a knight, being much smaller, would usually be concentrated within a single locality and would require only one base. As Mediaeval government was frequently incapable of guaranteeing peace and order, such bases needed to be defensible. Thus the castle was born. […]It should also be realized that life in a castle was predominantly a quiet, peaceful process. Castles were primarily the residences of the nobility and the gentry and the life lived in them was very much akin to that of the later country house. Indeed, we shall see that towards the close of the Medieval period, as society became more peaceful, castle design began to lay more stress on the comforts of life and less on the needs of defense. Contrary to the image portrayed by Hollywood, castles were not continuously in a state of siege, crowded with 13 armed men and ringing with the clash of arms! In times of peace, the castle would contain the owner's family and servants. The owner might frequently be absent, in which case, the castle would be occupied by only the caretaker and a few servants. In time of war, the castle would be garrisoned by the lord's tenantry, fulfilling one of their feudal obligations; castle-guard. Once the crisis was past, the garrison would revert to being farmers and farm workers. http://www.britannia.com/history/david1.html Source 13 According to this source, the feudal society had weakness that would lead to its downfall. Why did the system of feudalism last as long as it did? What contribution did feudalism give to modern societies? Feudalism was based on a legal agreement by which a lord granted land to a man in return for military service. Political and economic power was concentrated in the hands of lords and their vassals. Castles, each of which dominated the district in which it was situated, were the base for the exercise of that power. In theory, feudalism can be said to resemble a pyramid, with the lowest vassals at its base and the lines of authority flowing up to the peak of the structure, the king, but in practice, there were structural variations from nation to nation. The widespread custom of Feudalism was largely confined to northern France, western Germany, England, the Norman kingdom of Sicily, the Crusader states, and northern Spain. The Feudalistic system was only in operation for a short time before the first signs of its decay appeared. There were multiple reasons for the decline of Feudalism. One was the replacement of the feudal contract with the establishment of inheritance of fiefs. Once a fief was thought of as part of the heritage to be passed down from father to son the personal nature of the feudal contract was seriously undermined. A second reason for the decay was the introduction of new forms of warfare during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, which made the limited service of the feudal army of knights obsolete. The disintegration of feudalism was largely completed by the end of the fourteenth century. Constitutionally, the English-speaking world owes to feudalism the right of opposition to tyranny; representative institutions; resistance to taxation levied without consultation; and limited monarchy [since the king was bound by custom, by his own law, and by the necessity to practice self-restraint lest he be restrained by the community]. Feudalism also contributed the contract theory of government -- the idea that both the government and its citizens have reciprocal rights and obligations. Feudal legacies in cultural matters include Chivalry, from which many modern standards of a gentleman are derived; castle architecture; and, in writing, the epic, romance, and courtly literature. http://www.umfa.utah.edu/index.php?id=MTUx 14 Bonus Source a) Origins of Parliament - King's councils: The origins of Parliament go back to the 12th century, when King's councils were held involving barons and archbishops. They discussed politics and were involved in taxation and judgments. Parliament, as a political institution, has developed over hundreds of years. During that period the two distinct Houses – Commons and Lords – emerged and the balance of power between Parliament and the monarchy changed dramatically. Over time, these councils took a more formal role and saw knights representing each county. This was the beginning of a Commons element in Parliament. The word 'Parliament' was used to describe these meetings by the early 13th century. Two Houses: By the 14th century two distinct Houses, the Commons and the Lords, had developed. The Commons involved representatives from counties, towns and cities, the Lords already consisted of members of the nobility and clergy. Parliament and the monarchy: During the 15th century, King Henry V put the Commons on an equal footing with the Lords. http://www.parliament.uk/about/history/institution.cfm Bonus Source b) Where Our [Canadian] Legal System Comes From The common-law tradition: Canada’s legal system derives from various European systems brought to this continent in the 17th and 18th centuries by explorers and colonists. Although the indigenous peoples whom the Europeans encountered here each had their own system of laws and social controls, over the years the laws of the immigrant cultures became dominant. After the Battle of Quebec in 1759, the country fell almost exclusively under English law. Except for Quebec, where the civil law is based on the French Code Napoléon, Canada’s criminal and civil law has its basis in English common and statutory law. The common law, which developed in Great Britain after the Norman Conquest, was based on the decisions of judges in the royal courts. It evolved into a system of rules based on “precedent.” Whenever a judge makes a decision that is to be legally enforced, this decision becomes a precedent: a rule that will guide judges in making subsequent decisions in similar cases. The common law is unique because it cannot be found in any code or body of legislation, but exists only in past decisions. At the same time, common law is flexible and adaptable to changing circumstances. http://canada.justice.gc.ca/en/dept/pub/just/03.html 15