Evaluation and Assessment in the IB CAS Programme

advertisement

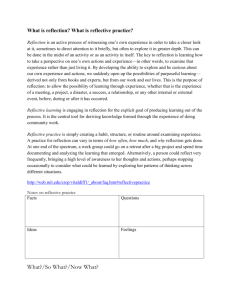

Assessment and Evaluation in the IB CAS Programme Introduction Evaluation and assessment are obviously an integral part of any learning programme, traditional quantitative measures have always been used in schools to monitor and assess academic progress, but questions remain as to whether the type of assessment we are used to will be valid when applied to an experiential learning scheme like CAS, where the emphasis is on self-realisation and reflective learning outside the traditional curriculum. Some of these questions might be: 1. Can the value of experience be assessed by anyone other than the person who undergoes the experience? 2. How can external criteria be applied to self-development when each student is different? 3. What criteria do we use to monitor and evaluate reflective learning? 4. How do we assess the merit of individual CAS programmes with so many varied activities? Or to put this in more direct terms: How can we assess progress when we don’t know what the starting point is, where we are at now and what the units of measurement are? In trying to devise a scheme which is both valid in terms of assessment and reliable over a large population we are also seeking to facilitate monitoring throughout the programme, and to ensure that the CAS programmes followed by individual students are relevant to them personally and faithful to the aims of the programme. Thus although it is tempting to start with the examination of different assessment and evaluation methods, this would be in a way putting the cart before the horse. Surely we need to start by examining the aims and objectives of the IB CAS programme and then look for tools which can be used: 1. 2. to show if, and to what extent, these are being achieved by students. to evaluate the quality of CAS activities in relation to these aims and objectives. This type of methodology should also try to get away from the counter-productive idea of using “CAS hours” as a measure of achievement. and hopefully provide the answer to the perennial student questions: Why do we have to do CAS? - Can I count this for CAS? - How many hours do I get? This presentation will attempt to do this by: Examining the aims and objectives of the IB CAS programme in the light of literature and previous research into experiential and reflective learning. Proposing evaluation and assessment tools which are valid, reliable and relevant. Presenting the results of the use of these tools in an IB CAS programme. In three fundamental areas: 1. Self-assessment 2. Reflective learning 3. CAS activities 1 PART 1: SELF-ASSESSMENT The following section reviews briefly literature in the fields of self-concept development, reflective and experiential learning techniques and examines methods by which these could be adapted for self assessment in the CAS programme, so that the “self-evaluation process encourages the development of critical thinking skills and enhances students’ awareness of their own strengths and weaknesses” (IBO, 2001, p30). A. The self concept The IBO expects self and school evaluation in the CAS programme to include “the extent to which they have developed personally as a result of the CAS Activity”; students should comment on the “the extent to which they have developed personally as a result of the CAS activity” (IBO, 2001, p30). It would seem unrealistic and even unreasonable to ask students to do this without any attempt to identify parameters on which this could be based and assessed. In order to do so we have to define what we understand by “personal growth and development”. i. Social Interactionism and Personal Construct Theory The idea of the self-concept has been developed in Western social psychology since the early psychologist William James, by Cooley and Mead through to Goffman and Rogers (Burns, 1979). Mead saw society as the birthplace of the self, and held that the self of any individual develops as a result of his relations to the process of social activity and experience and to others within that experience. In this social interactionist school of psychology, the self concept as an object arises in social interaction as an outgrowth of the individual’s concern about how others react to him. In Personal Construct Theory (Kelly, 1955) central constructs about the self are formed as a result of the individual’s interpretation of the reactions and behaviour of others. The placement and classification of an individual’s own behaviour and actions within this personal construct system come to define the self. They provide the basis for the individual’s plans and decisions regarding the choice of appropriate behaviour to meet unfamiliar situations (Burns, 1986). In Kellyan understanding of education learners cannot be divorced from their surroundings, the cultural constraints and possibilities within which their personal realities have developed, these include school and teachers, who have their own social and cultural identity. Most educators will be familiar with the circular process of self-concept, behaviour and feedback in schools as shown by Burns (1982) in Fig.1 This can sometimes become a vicious circle, with a corresponding negative self-concept. However, Mezirow's " perspective transformation”, Reed’s A the empowering learning process” and Freire's "conscientization” ( Boud et al., 1989) are all ways of describing the process in which assumptions about the self can be transcended through education. Salmon (1984) also explains how in Kelly’s approach to learning, everything can always be reconstrued. It is suggested here that a scheme with teacher/supervisors monitoring a programme of outside school experiential learning can break or re-define this cycle. CAS can give the opportunity for growth, positive enhancement of self-concept or a chance to re-define a self-concept based on primarily school experience at an important stage in the move towards adulthood. Pupil’s valuation of valuations and expectations held for him/her by significant others Fig.1 Teacher and parent feedback to pupil Pupil’s valuation and expectations of self Pupil’s self concept of ability Teacher and parent’s evaluation of pupil Expectations held for pupil by teacher and parent 2 Pupil’s behaviour and performance in classroom ii. Self-concept development and measurement Other studies of experiential learning programmes have looked at means of evaluation from the perspective of evaluation of the impact of the scheme (American Council on Education, 1978; ACTION, 1977; American Association of Community Colleges, 1995), evaluating service learning programmes (National Student Volunteer Program, 1977) development of qualities such as civic responsibility in students (Soltys, F.W. 1997), relation to academic performance (Fenzel and Leary, 1997) but have rarely attempted to identify or measure personal development or develop parameters for students to do so themselves. Many advocate the incorporation of reflective exercises (Silcox, H., 1993; Oates, 1996; Schratz and Steiner-Löffler, 1998) especially journal-keeping, into experiential learning programmes, but apart from Wang et al (1997) seem to neglect the comparative nature of evaluation which is required if the effectiveness of the programme in achieving the goal of student self-development is to be assessed. It is suggested here that some form of self-profiling is essential in order to: enable students to relate personally to the CAS programme allow them to identify parameters on which to base self- and activity evaluations provide a basis for comparative self-assessment Tools to measure self-esteem have been developed by Coopersmith (1967), Button (1982), Wells (1983), among others, but are based on external parameters which can be seen to be at least culture-specific, if not classspecific. Kelly suggests that techniques to aid reflection must be applied to the constructs of the learner (Boud et al, 1985), therefore his Personal Construct Theory has added benefit as the choice of student self-concept assessment. Many Personal Construct Psychology elicitation methods have been derived from the work of Kelly (1955) by for example, Shaw (1981), Easterby-Smith (1981), Salmon (1984), Bannister and Fransella, (1986), and Pope and Denicolo, (1993). These can give us a profile of a student’s self-concept using their own constructs, rather than those which have been devised by the author of the instrument. Elicitation of constructs in this way also enables cultural differences to be accommodated. One form of elicitation uses Triadic Elicitation to form what are known as Repertory Grids, and this can be used with groups as well as individuals. Constructs relating to student self-concepts can be elicited via semi-structured group interviews "One use of the (repertory) grid with groups has been to abstract the constructs used and form them into a more conventional attitude measure, i.e. find a yardstick from a particular population or sample in which the research interest is focused” ( Pope and Denicolo, 1991). The inferred constructs can be combined into a self-profile grid, which incorporates principles of Likert scales ( Robson, 1998), semantic differentials (Osgood et al in Pope and Denicolo, 1991, Robson, 1998), and Salmon lines ( Salmon, P 1995), with bi-polar evaluative continua divided into 7 segments. The resulting self-profile grid is shown in Fig. 2, but the constructs obtained may differ between groups and between schools. Students can thus obtain a self-profile related to their own idea of growth and self-development, which can be used not only as a form of assessing self-development, but also as individual criteria for the choice of CAS activities. This will enhance the choice of effective CAS activities and also increases the relevance of the whole CAS programme to the student. “Through all the activities that I have been doing I learnt many things. At the beginning of the year I did not have such a positive way of thinking but now I think I do. I was always thinking about what other people would think if I do a certain thing. I did not have confidence in me and I always tried to follow others. But now I do not have that habit any more. I had an opportunity to do presentation in front of many people and organize something in big scale. All of them actually worked, other people were interested in our project and we got big corporation. It gave me a great influence. At that point I realized that if I try to achieve something and work on it, I actually be able to make it happen”. The self-evaluation from which the above extract is taken includes the pronoun ‘I’ 44 times! As one student remarked: “ Now I understand what CAS is about…. It’s about me” 3 Figure 2 Self-profile Grid (Allan, 1999) 2. REFLECTIVE LEARNING “The most socially useful learning in the modern world is the learning of the process of learning, a continuing openness to experience and incorporating into oneself of the process of change.” (Rogers, 1969) The IBO guidelines also stress that "the emphasis of CAS is on experiential learning” (IBO, 1996, p4) and that "self-evaluations should be reflective rather than descriptive, narrative reports” (ib.p5). This section will explore how these ideas of experiential learning and reflection are inter-related, and how we may observe and evaluate the process to determine if experiential learning really is taking place. A. Turning experience into learning In his 1916 Paradigm for Reflection, Dewey stated that reflection required: a definable problem, an extended period of analysis and a hypothesis tested by some action. Jurgen Habermas, in 1979, emphasised the importance of intention, "critical intent”, the bringing of informed judgement to bear on the validity of questions ( in Boud et al., 1989). Current notions of reflection are that it is always focused on the problem and that it is oriented towards action. Kolb (1975) describes the process of reflection as a cycle of experience, observations and reflections, forming of abstract concepts and generalisations, and the testing of their implications in new situations (Fig 3). The idea of reflection as a cycle involving action and revision of plans leading to further action has been extended by Stephen Kemmis (in McNiff et al.,1996). He defines the reflective process as “meta-thinking”, thinking about the relationship between 4 action and thinking. He characterised an effective reflective process as a spiral (Fig 4), involving a continuous process of planning, monitoring, reflection and evaluation leading to revised plans and a new cycle. Experiential learning schemes like CAS enable a movement from what can be a vicious circle in schools, as shown by Burns (1982) in Fig.1, to a potentially virtuous one like Kolb’s. Concrete experience Observations and reflections Testing implications of concepts in new situations Formation of abstract concepts and generalizations Fig. 3 Kolb’s Description of the Learning Cycle (Kolb and Fry, 1975) It is suggested here that the real value of the CAS programme can best be understood and appreciated in this light, and staff and student involvement can be transformed if its true educational value can be appreciated. B. Praxis – turning reflection into action However reflection involving action is not automatic. Kemmis holds that the intent of the learner permeates every stage of the process from choice to engage in a particular activity to the results of the reflective process. How then can reflection be stimulated and facilitated within an experiential learning programme such as CAS? Guiding students in the process of reflection is not easy, Tucker et al (1996) suggest that the teacher should be: Anon-judgemental, listening, praising, non-critical and non-problem-solving”. Research into the use of Dialogue Journals (Staton, J.1987; Kreeft-Peyton, 1993) confirms this and adds that teachers should try not to be prescriptional, but perhaps quote from their own experience in order to offer to pupils some avenues of exploration. In short, teachers should function as a meta-guide, helping the learner to focus on the reflective moment, to identify the A critical incident”. i. Planning The first point of guidance needed by the student is in the choice of activities. Self-concept profiling should have given an idea of the areas which the student can develop through CAS, planning should incorporate this and translate it into specific aims and objectives for the activity. Together these give a starting point for reflective learning and a basis for meaningful self-evaluations. Research on goal-setting shows that individuals with negative self-concepts set goals unrealistically high or low. This ensures that whatever the real outcome, it will be construed as failure. Those with positive self-esteem use goal-setting to maintain the self as known and attribute blame for failures to others. Unrealistic evaluations tend to compound generalisations of failure. Realistic negative evaluation should provide a basis for change that is based on previous evaluations, comparing present with past performance instead of that of others. Students will need help, first in setting realistic goals and second in planning how to work towards these on a realistic time-scale. One method of doing this is by the use of a proposal incorporating aims in terms of personal development, and specific objectives for the activity, planning as to how to achieve these, together with a time line. This should be submitted before a student can start an activity, and has the added benefit of automatic monitoring of the suitability of the activity in terms of general IB criteria. (See Part 3). 5 Figure 4: The Spiral of Kemmis 6 ii. Student journals Journals have been used as vehicles for reflection since early times (Goldsmith, 1996). They have been found to provide tangible evidence of mental process (Staton, 1987; Tucker et al., 1996; Peyton, 1993; Goldsmith, 1996; Kerka, 1996) they demonstrate movement through Kolb’s Modes of Experiential Learning or Spiral of Kemmis (facilitating monitoring). They can become vehicles of experiential learning in: 1. recording a concrete experience or feeling. 2. reflecting on and observing the experience. 3. integrating observation into abstract concepts or theories. 4. using theories to make decisions and solve problems. As Clark, (1994, in McIntyre and Tlusty, 1995) says: "Journals are tools for growth through critical reflection” They are intended to illustrate, facilitate and enhance reflection and therefore evidence of the reflective cycle as described above should be monitored. Because of the importance of reflective learning in the programme, the type of reflection to be seen in student journals is more important than the amount; any evaluation then should be qualitative, not quantitative. Firstly journals can be analysed for reflective, narrative and descriptive content. Any reflective content found can then be analysed and differentiated into 3 levels. 1 Recording, reflecting on and observing a concrete experience or feeling ‘‘reflection-on-action’ as retrospective and hypothetical, not causally linked with a subsequent action (Schön, ibid) "Descriptive reflection” (Hatton and Smith, ibid) 2 As level 1 plus: Integrating observation into abstract concepts or theories "reflection-in-action”-respond to surprising findings by inventing new rules on the spot” (Schön, ibid, p3) "Dialogic reflection” (Hatton and Smith, ibid) 3 As level 2 plus: Using theories to make decisions and solve problems evidence of critical intent and praxis "our thinking serves to reshape what we are doing while we are doing it” (Schön, ibid), "Critical reflection” ( Morton , 1993 in Tucker, 1991) Table 1: Levels of reflection (Allan, 1999) However, it must be remembered that the journal is the vehicle by which the student evaluates his/her own programme in relation to self-development, it is not what is being assessed. Journals should not be evaluated, they are an evaluation. However they demonstrate the effectiveness of the student’s reflective learning, which can be evaluated by supervisors. This needs to be continuous rather than summative and is more to monitor than to assess. Teachers should provide feedback and act as guides and monitors in this respect the student evaluates, the teacher moderates iii. Results This section provides some extracts from student journals in order to demonstrate more clearly how different levels of reflection can be seen and how they relate to the effectiveness of any experiential learning taking place a)Personal Journals Level 1 reflection, “reflection-on-action”. This consists of recording feelings and thoughts about activities which were undertaken, in many cases after the activity has been completed. Extracts of this level are given below: S30 “....we had to cook, serve and clean all! However this wasn’t a problem since you acquire a sense 7 of responsibility for all the children you’re supervising and feel like a “complete” adult. When people rely on you, you wouldn’t want to let them down .” S25 “Feb 27th 1999 - We are actually moving the heavy furniture! The house is actually nice! I feel that the house is, in a way, partially mine, due to all the energy I have put into it. From the removal of the wallpaper to moving the heavy furniture in, I have helped Yoav over a scope of tasks” Level 2 reflection, “reflection-in-action”, showing identification of critical incidents, reflection on them and the drawing of conclusions from the reflection. S08 “- It was hard trying to understand the people and one had to take care not to personally take the comments an elderly says. - I felt really bad today since I tried to help an old lady eat but she couldn’t and I couldn’t do anything. - It is nice being around old people once in a while since you realise the importance of life and how good it feels to be young and be able to eat your food.” S38 “This camp got me talking to a lot of new (to me at least) people. I made new friends and I became less shy about approaching strangers. I discovered that nearly everyone is looking for friends in this world and not enemies, so just and be friendly.” S29 “Day 5 Feb 27 - Came at about 3.00. Saw Jean outside. Helped feed the animals and chatted to Jean. Really cool company. Get the feeling I’m really appreciated. Male goat tried to escape. Now allowed to do even more on my own.. e.g. the rabbits, chickens, goats and the sheep. Going next week again. Enjoy the work: helping someone, improving my communicating skills, feeding animals, not very tiresome, but fun! Most importantly I learn how to get on with all sorts of people. I feel much more confident now, not shy to say what I think and feel”. Level 3 reflection, Praxis -“reflection-in-action” taken further, where conclusions from reflection had then been tested by modifying action or initiating new action, and evidence of “intent” was present. S34 “11 February 1999 - We had a rehearsal for tomorrow’s presentation. It was one of my objective ‘to be able to talk in front of many people’. ........... I hope I can manage to talk confidently tomorrow. After I got home I rewrote my speech. I heard other people’s speech and I thought mine is too formal.. or too boring. To impress people it will be nice to be a bit informal especially in our situation because listeners are all students who we always meet. Though my speech is still not so funny(?)...” “17 April 1999 - I talked to my supervisor about the creations that I have been making. She gave me some very nice advice. She told me to look for more modern ways of making jewels. I thought I was doing some experimental work but I realised that all of the design was almost the same and have no significant changes. I read some books and saw some artists’ creation and they were so much different. They had full of imagination and it was very creative. So I decided to make something totally strange and new. I would like to use some weird materials such as coke can or some plastic pieces etc. even chopsticks can be useful.” b) Dialogue journals One effective way of monitoring and guiding reflection is the “Dialogue Journal” where the supervisor reads the journal and adds their own comments, it thus takes the form of a dialogue between student and supervisor. Dialogue journals showed examples of Level 2 Reflection (“reflection-in-action”, showing identification of critical incidents, reflection on them and drawing conclusions from the reflection). In nearly all cases this was accompanied by comments from the supervisor drawing their attention to various points. S38 “Before we even got started I knew it would be quite a challenge getting the 4 of us to work together as a group...........After we started I knew for sure it would be tough. Quite honestly not one of us seemed all that interested in spending time with the rest to get some concrete plans for the sketches. My personal opinion, that there was a lack of co-operation was proven right when S39 wrote the play by himself.....” Supervisor “Your comments on the effort put into the......... play are very honest (I think you’re right - that unless people commit themselves, the results won’t amount to very much).” “..........your comments are interesting, but perhaps you should put in more about yourself - write down how you felt about your aims and development - to what extent did you achieve or fail to achieve what you set out to do”. S38 “I already feel that my love for acting is no longer the same, but I will keep on going with this activity at least for a bit longer to give my feelings a chance 8to really develop.” c) Other journal types One of the complaints of students regarding journal-keeping was the extra time involved. However a wellwritten journal is a creative activity, and can be counted as such in terms of CAS. Students often incorporate photos, programmes, newspaper reports into their journals, and there are many forms other than the familiar personal journal. 8 students used e-mail to communicate and discuss a project they were working on. These communications were then collated to form a group electronic journal. The content was more current than other types of journal, contained very little narration or description but a much higher amount of Level 3 reflection. 11 students carried out a project involving interviewing and photographing other students about their CAS activities. These were then published electronically, and in some cases in the school magazine. The distribution of narrative, descriptive and reflective content was about the same as the personal journals. Attempts were made to also compile photographic journals and a web page where a “chat-room” could be established to discuss CAS activities. Difficulties involving technical problems and time management by the groups involved meant that these were not completed in time for analysis. A video journal was started, recording ‘snapshot’ interviews with students and some CAS activities. 3. CAS ACTIVITIES IBO Guidelines say that CAS activities should: challenge and extend the student develop awareness, concern and the ability to work cooperatively with others complement the academic curriculum and provide balance to the demands of scholarship enhance their personal growth develop a spirit of open-mindedness, lifelong learning, discovery and self-reliance encourage the development of attitudes such as determination and commitment, initiative and empathy. (IBO, 2001, p 3) and should not be: part of the required curriculum translation of documents for reward, financial or benefit-in-kind a passive activity e.g. museum, theatre, concert visits part of family (IBO, 2001, pp 5-6) The above guidelines can be used to classify qualities of CAS activities into 7 criteria, with 4 descriptors of ascending levels of achievement for each criterion. These can then be combined to form an assessment rubric, constructed on the principles of Hayes Jacobs (1997) this can be used for monitoring and evaluation of the quality of CAS activities, and an individual CAS programme’s effectiveness in meeting stated goals. These rubrics can be used by students, while choosing activities; by supervisors, to monitor the suitability of activities, and as a record and means of evaluation of each student’s individual CAS programme. Together with the comparative self-assessment and the journal evaluation a profile of each student’s programme can be obtained, to be used in the school’s evaluation. 9 CAS Activity Evaluation Rubric (Allan, 1999) Criterion A B C Challenge Level 1 E Level 3 attendance only gives opportunity for student to presents a difficult and challenging required extend himself target Opportunities for service, no benefit to other has some benefit to others outcome is directed towards benefit to others than student Acquisition of skills and no level of skill requires skills any student of this interests rather than practising required age would be expected already to those already acquired D Level 2 benefiting others develops existing skills Level 4 pushes student beyond previous limits results in identifiable benefit to others develops new skills have Initiation and planning by activity organised by activity organised by outside organised by group of students with planned, organised and run by students school agency adult leader student (s) Establishing links with does not involve involves working within the involves working with the involves working with and within community and furthering working with others school community only community but may only be with the local community and/or in the student’s own nationality or local language international understanding international community F Active rather than passive no active participation student required to participate but requires active participation nature G not initiate requires active participation and input from student Project nature - combining 3 activity ‘one-off’ of combines two activities on more has elements of all three activities has a good balance of three types of activity (creative, active short duration only than one occasion or one for on more than one occasion or two activities combined into a long and service) one type longer duration for longer duration term project 10 CONCLUSION In this presentation an attempt has been made to articulate the philosophy and objectives of the CAS programme in terms of the educational and psychological theory which underlies it. It has been described as a scheme where the self, as well as personal and other skills, can be developed by students in a scheme where the setting of goals, planning, experience, monitoring, reflection, praxis and evaluation all form an integral part of the experiential learning cycle. As such it holds a unique place, at the core, of the IB Diploma curriculum, and does so much to distinguish this programme from other, purely academic, post-16 educational programmes. It can be seen to provide learning opportunities that are not available within a normal school structure, one which incorporates traditional quantitative means of assessment. The evaluation of success in a CAS programme corresponds much more closely to real life, in the setting and achievement of authentic personal goals and objectives. Its educational value lies in the fact that students learn how to monitor and evaluate their own progress, and develop the reflective learning techniques, learning how to learn, which are invaluable in a rapidly changing world, where learning is for life. Learning from experience is not automatic, as Huxley once remarked “The only thing that people learn from History is that people don’t learn from History”. This presentation has tried to outline a structure, and the techniques required, which enable students to learn how to learn from experience. It has asserted that 1. 2. 3. A student’s CAS programme must be related to a student’s personal qualities, aims and ambitions for it to have any relevance and learning value. The setting of goals, planning to achieve them and assessment of success are fundamental to experiential learning. The development of critical reflection and praxis are essential to success. And that these factors are inter-linked and interdependent, as are the assessment and evaluation tools described which are part of and essential to the process. 1. 2. 3. Self-concept profiling gives the student a starting point for choice of activities, planning and evaluation. Journals are vehicles through which reflective learning can be developed, monitored and evaluated. CAS programmes can be evaluated on their relevance to individual experiential learning. In the pilot study, it was observed from the student profiles that the most significant changes in selfconcept were shown by students whose journals showed evidence of the highest level of reflection, and whose CAS programmes scored highest on the established criteria. The evaluation of self-development by self-concept profiles, and the evaluation of experience in reflective journals can not be divorced from the learning process and must be carried out by the student. However the criteria given for assessing reflective learning and relevance of CAS programmes give supervisors the opportunity to monitor and guide learning, and the quality of each student’s programme in relation to his/her own development and the aims of the CAS programme in general. Again we can use the analogy of the student as his/her own “examiner” and the CAS supervisor as the “ moderator”. It is hoped therefore that the questions posed in the introduction have been answered to a large degree, but one pressing and fundamental question now arises, “What do we do with the information we now have available?” CAS is the only element of the IB Hexagon in which “satisfactory” completion is a passing requirement for the Diploma. Do we say that no evidence of self-development, critical reflection or a minimum score CAS programme are failing conditions? Do we use the criteria as a basis for awarding grades, merits or distinctions? or Do we say that the benefits to the student of successful completion of a CAS programme are the best rewards they could get? 11 REFERENCES Allan, M.J. (1999) The Introduction of Reflective Learning Techniques in the IB CAS Programme, unpublished Intervention Study, Oxford Brookes University: Oxford American Association of Community Colleges (1995), Community Colleges and Service Learning, Michigan, Kellogg Foundation. American Council on Education (1978) Service Learning for the Future. Domestic and International Programs, Michigan: ACTION. Bannister, D. and Fransella, F. (1980), Inquiring Man: The Psychology of Personal Constructs, London: Croom Helm. Boud, D., Keogh, R. and Walker, D. ( 1989), Turning Reflection into Learning, London: Kogan Page. Burns, R. (1979), The Self Concept: Theory, Measurement, Development and Behaviour, Harlow: Longmans. Burns, R. (1982) , Self Concept Development and Education, London: Holt, Rhinehart and Winston Ltd. Button, L (1982), Group Tutoring for the Form Teacher ,London: Hodder and Stoughton. Coopersmith, S. (1967) The Antecedents of Self-Esteem, San Francisco: Freeman and Co. Dewey, J. (1933) How We Think, Boston: D C Heath. Fenzel, L.M. and Leary, T.P (1997) Evaluating Outcomes of Service-Learning Programs at a Parochial College, Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of American Educational Research Association, Chicago: EDRS. Goldsmith, Suzanne, (1996) , Journal Reflection,: A Resource Guide for Commmunity Service Leaders and Educators Engaged in Service Learning, Washington DC: The American Alliance for Rights and Responsibilities. Hatton, S. and Smith, D. (1995) Reflection in teacher education: towards definition and implementation: Teacher and Teacher Education, 11,(1), 33-49. IBO, (2001)DIPLOMA PROGRAMME, Creativity, action, service, IBO Geneva Kelly, G.A., (1955) The Psychology of Personal Constructs, New York, W.W. Norton. Kemmis, S and McTaggart, I. ( (1983) The Action Research Reader, Geelong, Victoria,: Deakin University Press. Kerka, S. (1996) Journal Writing and Adult Learning, Eric Digest No 174, EDRS. Kolb, D.A. and Fry, R. (1975) Towards an applied theory of experiential Learning, in Cooper, C.L. (ed) Theories of Group Processes, London, John Wiley, pp33-58. Kreeft -Peyton, J, (1993), Dialogue Journals: Interactive Writing to Develop Language and Literacy, ERIC Digest Issue July 1993, EDRS. McIntyre, S.R. and Tlusty, R.H., (1995) , Computer Mediated Discourse: Electronic Dialogue Journaling and Reflective Practice, Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of American Educational Research Association, San Francisco, Ca., Apr18-22, 1995. McNiff, J., Lomax, P. and Whitehead, J. (1996), You and Your Action Research Project, London: Hyde Publications. National Student Volunteer Program, (1977) Evaluating Service-Learning Programs. A Guide for Program Coordinators, Washington DC: ACTION Pope, M. and Denicolo, P. (1991) The Art and Science of Constructivist Research in Teacher Thinking, Teacher and Teacher Education, Vol 9, No 5/6, pp529-544, Pergamon Press. Robson, C. (1990) Real World Research, Oxford: Blackwell. Salmon, P., (1995) , Psychology in the Classroom, London: Cassell. Schon, D.A. (1983) The Reflective Practioner: How Professionals Think in Action, London: Temple Smith. Schratz, M and Steiner-Liffer, U., (1998) Self Evaluation,: A Visual Reflection, Managing Schools Today, February 1998. Shaw, M.L.G., (1981), Recent Advances in Personal Construct Theory, London: Academic Press. Silcox, H.C. (1993) Adding Cognitive Learning to Community Service Programs, Holland PA: Brighton Press Inc. Soltys, F.W., (199700, Pima Community College Service Learning Handbook, Tucson, Ariz: Pima Community Coll. Staton, J, (1987), Dialogue Journals, Eric Digest Issue Dec 1987, EDRS. Tucker, B. , Wood Foreman, C. and Buchanan, P. (1996) What is Reflection? Process Evaluation in Three Disciplines, Paper presented at the Annual Conference for Integrative Studies,18 th, Ypsilanti, MI, October 3-6, 1996. Wang, J., Greathouse, B. and Falcinella, V.M. (1997) An Empirical Assessment of Self-Esteem Enhancement in a CHALLENGE Service- Learning Program, Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research12Association, Chicago, Ill. March 24-28, 1997.