Mercury`s dark influence on art

advertisement

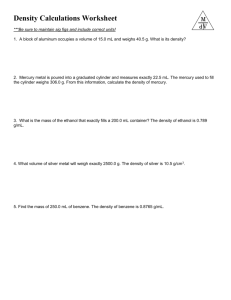

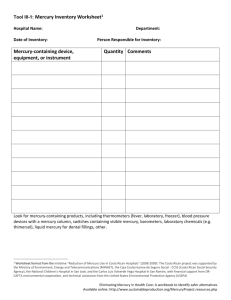

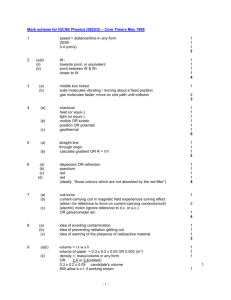

CONCOURS D’INGENIEURS DE LABORATOIRE DU MINISTERE DE L’ECONOMIE ET DES FINANCES DU 22 JANVIER 2014 Concours interne : spécialité chimie analytique ÉPREUVE N° 2 Traduction d’un document technique rédigé en langue anglaise ; Réponses en langue française à des questions portant sur le document. Durée : 2 heures - coefficient 1 2 A -Traduire le titre et les deux premiers paragraphes du texte ci- . dessous (partie encadrée) B - Répondre en français aux 2 questions suivantes : 1 - Pouvez-vous décrire les travaux réalisés par les différentes équipes de chercheurs ? 2 - À quoi ces travaux peuvent-ils servir ? Mercury's dark influence on art The brilliant red pigment vermilion has been widely used since antiquity on monastic murals and baroque paintings. But a chemical mystery has dogged this paint, as when it ages it darkens. Scientists have long suspected a thin film of mercury may be responsible for the blackening, but have been unable to prove that this was the case. Now two papers from researchers in Belgium have begun to unravel just what is going on at the surface of these works of art. Vermilion was first made from the mineral cinnabar, mercury sulfide, but was subsequently produced synthetically. First used in 7000–8000BC, it was highly prized in ancient Rome and was the principal red pigment used by European painters during the Renaissance until the 20th century, when it was finally superseded by the cheaper and safer cadmium red. In 2005, Katrien Keune and Jaap Boon of the FOM Institute for Atomic and Molecular Physics in Amsterdam proposed that chlorine salts in the air catalysed the photodecomposition of mercury sulfide into elemental mercury, which appears black in thin layers. Mercury, however, is extremely difficult to detect because, as a liquid metal, it does not have a regular crystal structure to diffract radiation, making it invisible to x-ray diffraction and absorption spectroscopy. Back to black To investigate this hypothesis, researchers at the University of Antwerp dipped a piece of platinum covered with vermilion into an aqueous solution of chloride ions and then irradiated it with laser light. Sure enough, it turned black. By applying a voltage to the blackened pigment, they found that mercury ions were released into the solution. The voltage needed to achieve this was exactly the voltage required to liberate mercury ions from metallic mercury. 3 In parallel, European researchers led by theoretician Fabiana Da Pieve, of the University of Antwerp and Vrije Universiteit Brussel, used density functional theory and other theoretical techniques to calculate how mercury might end up on the surface of degraded paint. They confirmed, in work accepted for publication in Physical Review Letters, that mercury sulfide ought to attract chlorine atoms from chloride salts commonly found in humid air. They concluded, however, that even in the presence of these, the photons absorbed by vermilion would have insufficient energy to cause direct decomposition of the mercury sulfide into elemental mercury. They calculated that the chlorine atoms could, however, be absorbed into the mercury sulfide lattice, forming the mineral corderoite (Hg3S2Cl2). The oxygen in the air could react with this to form sulfur dioxide, leaving behind an unstable defect in the corderoite lattice that, when hit by a photon, would collapse, releasing an atom of metallic mercury. Furthermore, the mineral calomel (Hg2Cl2) left behind can then dissociate to yield more metallic mercury. Evidence builds To confirm this, the researchers looked at micrometre-scale samples of degraded vermilion paint from murals in the Monastery of Pedralbes in Catalonia. Highresolution x-ray diffraction showed that a layer of corderoite lay on top of the original mercury sulfide, and on top of this was a layer of calomel, implying that each layer had formed from chemical degradation of the layer beneath it. ‘At the very top there should have been mercury,’ explains Da Pieve, ‘but mercury itself cannot be detected by this technique unless you do it at very low temperatures.’ Boon is impressed by the experimental demonstration, but he remains unconvinced that the multi-stage theoretical model is applicable in all cases. ‘As far as I can tell they say that the chloride is there in much larger amounts,’ he says, ‘and maybe that explains why the mechanism that they are proposing might work in their case [of the Monastery of Pedralbes].’ In some paintings kept in controlled environments, however, he still believes the chlorine is likely to be only a catalyst. ‘Some really good chemical work is now necessary,’ he says. Da Pieve hopes that a fuller understanding of the processes leading to vermilion degradation may, in time, lead to art galleries being able to prevent it or slow it down by, for example, excluding certain frequencies of light from museum and art galleries' lights. ‘I guess they already use lights of specific frequencies,’ she says, ‘but it could help to choose those frequencies in a better way.’ Tim Wogan CHEMISTRY WORLD NEWS, 29 OCTOBER 2013 4