Economics and Law Discussion Questions for 11/04/2010 1. Plaintiff

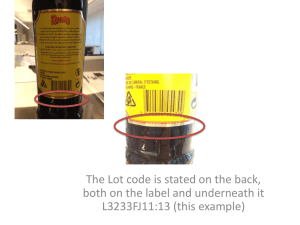

advertisement

Economics and Law Discussion Questions for 11/04/2010 1. Plaintiff, a waitress in a restaurant, was injured when a bottle of Coca Cola broke in her hand. She alleged that defendant company, which had bottled and delivered the alleged defective bottle to her employer, was negligent in selling "bottles containing said beverage which on account of excessive pressure of gas or by reason of some defect in the bottle was dangerous ... and likely to explode." Defendant's driver delivered several cases of Coca Cola to the restaurant, placing them on the floor, one on top of the other, under and behind the counter, where they remained at least thirtysix hours. Immediately before the accident, plaintiff picked up the top case and set it upon a near-by ice cream cabinet in front of and about three feet from the refrigerator. She then proceeded to take the bottles from the case with her right hand, one at a time, and put them into the refrigerator. Plaintiff testified that after she had placed three bottles in the refrigerator and had moved the fourth bottle about eighteen inches from the case "it exploded in my hand." The bottle broke into two jagged pieces and inflicted a deep five-inch cut, severing blood vessels, nerves and muscles of the thumb and palm of the hand. Plaintiff further testified that when the bottle exploded, "It made a sound similar to an electric light bulb that would have dropped. It made a loud pop." Plaintiff's employer testified, "I was about twenty feet from where it actually happened and I heard the explosion." A fellow employee, on the opposite side of the counter, testified that plaintiff "had the bottle, I should judge, waist high, and I know that it didn't bang either the case or the door or another bottle ... when it popped. It sounded just like a fruit jar would blow up. ..." The witness further testified that the contents of the bottle "flew all over herself and myself and the walls and one thing and another." The top portion of the bottle, with the cap, remained in plaintiff's hand, and the lower portion fell to the floor but did not break. The broken bottle was not produced at the trial, the pieces having been thrown away by an employee of the restaurant shortly after the accident. Plaintiff, however, described the broken pieces, and a diagram of the bottle was made showing the location of the "fracture line" where the bottle broke in two. One of defendant's drivers, called as a witness by plaintiff, testified that he had seen other bottles of Coca Cola in the past explode and had found broken bottles in the warehouse when he took the cases out, but that he did not know what made them blow up. However, defendant presented evidence tending to show that it exercised considerable precaution by carefully regulating and checking the pressure in the bottles and by making visual inspections for defects in the glass at several stages during the bottling process. 2. Stella Liebeck of Albuquerque, New Mexico, was in the passenger seat of her grandson's car when she was severely burned by McDonalds' coffee in February 1992. Liebeck, 79 at the time, ordered coffee that was served in a styrofoam cup at the drivethrough window of a local McDonalds. After receiving the order, the grandson pulled his car forward and stopped momentarily so that Liebeck could add cream and sugar to her coffee. Liebeck placed the cup between her knees and attempted to remove the plastic lid from the cup. As she removed the lid, the entire contents of the cup spilled into her lap. The sweatpants Liebeck was wearing absorbed the coffee and held it next to her skin. A vascular surgeon determined that Liebeck suffered full thickness burns (or thirddegree burns) over 6 percent of her body, including her inner thighs, perineum, buttocks, and genital and groin areas. She was hospitalized for eight days, during which time she underwent skin grafting. Liebeck, who also underwent debridement treatments, sought to settle her claim for $20,000, but McDonalds refused. During discovery, McDonalds produced documents showing more than 700 claims by people burned by its coffee between 1982 and 1992. Some claims involved thirddegree burns substantially similar to Liebecks. This history documented McDonalds' knowledge about the extent and nature of this hazard. McDonalds also said during discovery that, based on a consultants advice, it held its coffee at between 180 and 190 degrees fahrenheit to maintain optimum taste. He admitted that he had not evaluated the safety ramifications at this temperature. Other establishments sell coffee at substantially lower temperatures, and coffee served at home is generally 135 to 140 degrees. Further, McDonalds' quality assurance manager testified that the company actively enforces a requirement that coffee be held in the pot at 185 degrees, plus or minus five degrees. He also testified that a burn hazard exists with any food substance served at 140 degrees or above, and that McDonalds coffee, at the temperature at which it was poured into styrofoam cups, was not fit for consumption because it would burn the mouth and throat. The quality assurance manager admitted that burns would occur, but testified that McDonalds had no intention of reducing the "holding temperature" of its coffee. Plaintiffs' expert, a scholar in thermodynamics applied to human skin burns, testified that liquids, at 180 degrees, will cause a full thickness burn to human skin in two to seven seconds. Other testimony showed that as the temperature decreases toward 155 degrees, the extent of the burn relative to that temperature decreases exponentially. Thus, if Liebeck's spill had involved coffee at 155 degrees, the liquid would have cooled and given her time to avoid a serious burn. McDonalds asserted that customers buy coffee on their way to work or home, intending to consume it there. However, the companys own research showed that customers intend to consume the coffee immediately while driving. McDonalds also argued that consumers know coffee is hot and that its customers want it that way. The company admitted its customers were unaware that they could suffer thirddegree burns from the coffee and that a statement on the side of the cup was not a "warning" but a "reminder" since the location of the writing would not warn customers of the hazard. What damages should be awarded in this case?

![저기요[jeo-gi-yo] - WordPress.com](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/005572742_1-676dcc06fe6d6aaa8f3ba5da35df9fe7-300x300.png)