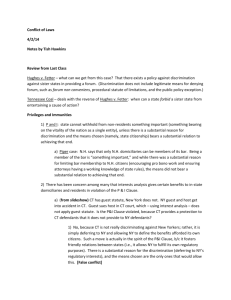

Neuborne - NYU School of Law

advertisement