Social Physics, by Auguste Comte (1798

advertisement

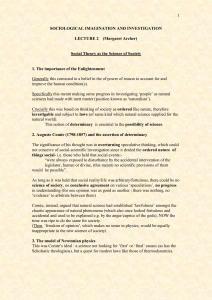

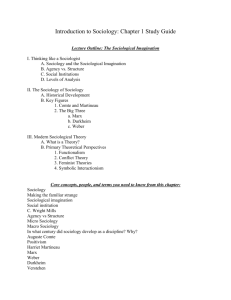

French philosopher and father of sociology; the first technocrat; wanted sociology to be queen of social sciences, guiding science like a benevolent king or Machiavellian advisor, lived through Napoleon I and III and Second Republic (1848) Social Physics, by Auguste Comte (1798-1857) Book VI of Cours de Philosophie Positive (1830-1842), In Auguste Comte and Positivism: The Essential Writings (Edited by Gertrud Lenzer) Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1975. Book report by Rich Hogan In explaining the need for a positivist social science (sociology), Comte argues that sociology can synthesize the elements of order and progress, which “the ancients used to suppose … to be irreconcilable” (p. 197). In fact, Comte argues, “No real order can be established, still less can it endure, without progress, and no great progress can be accomplished if it does not tend to the consolidation of order” (p. 197). Comte lays out the basic principles of positivist science (deductive theory and inductive proof: see chapter 3) and then treats order (social statics—rooted in morality, family, and ultimately government: see chapter 5) and change (social dynamics—rooted in economy but accommodated if not regulated by government: see chapter 6). Most important, in chapter 1 he outlines his evolutionary theory of society: society evolves from theological stasis (stability: stage 1) to metaphysical anarchy (change: stage 2) and, finally, to positivist science (the synthesis of order and change: stage 3). In this regard, Comte provides the basis for social science and positivist sociology, as it came to dominate the Western world (particularly England, France, Germany, and the U.S.). His focus on ideas (or, more accurately, on the basis for determining socially acceptable “truth”—theology, metaphysics, or positivism ) provides an alternative to biologically based “social darwinism” (see Spencer) and paves the way for Durkheim’s analysis of social statics/dynamics in material and nonmaterial “social facts,” which ultimately led to Durkheim’s theory of solidarity and social change (see Division of Labor). Comte’s concern with the problem of order and change set the intellectual (and political) agenda for Parsonian structural functionalism (which dominated sociology in the U.S. between World War II and the 1960s (actually, well into the 1970s, and it’s influence is still evident)). In this regard, American sociologists of the 1950s considered Comte the “father” of sociology.