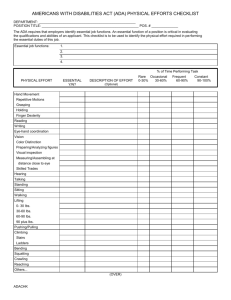

Overview of ADA Title III

advertisement