The Role of Legislation in Preventing Educator Sexual

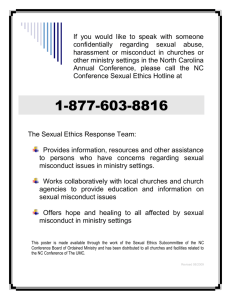

advertisement

International Issues in Protecting Children from Sexual Abuse by a Teacher The South China Morning News recently published a story on child sexual predators who have come to China and become teachers so that they can sexually abuse children. A British citizen, who had been teaching in Beijing for 5 years and in other locations in China since 2002 was arrested for sexual abuse of his students. At nearly the same time, an Australian citizen was arrested for sexually abusing four boys in the Philippines. He had been serving as head of the Ahuhai International School a month earlier. An American kindergarten teacher was arrested in Shanghai where he was teaching. Another teacher, a foreign national, was also arrested. Michael Dunne, notes that child sexual abuse “is a significant problem in Southeast Asia” and that “there are so many reports all over China, but we don’t know how widespread that it.” Southeast Asia is not unique in the existence of child sexual abuse, which occurs across the globe. Teachers as predators is a topic that is not clearly understood at the international level, since few studies have been done. In the United States, we have a handful of studies that on educator sexual misconduct. A national survey of students found that 7% had experienced physical sexual misconduct from a teacher or other professional in the school and 10% had experienced some form of misconduct to include physical, visual or verbal (Shakeshaft, 2004). In the U.S. these statistics translate into 3.5 million K-12 students who, at any one time, have been sexually physically targeted by an adult working in the school. If visual and verbal abuse is added, the number rises to 10% for school-related predation. That is 4 million students in the U.S. A recent Associated Press study documents that 2500 teachers have been decertified in the last five years for sexual exploitation of students and that number reflects only the cases that have gone through the criminal justice system or through state professional practices boards. Most sexual exploitation by school personnel (88%) is not reported to an authority. The issue of educator sexual misconduct, and the larger category of “trusted other” sexual abuse, has received little attention in the research literature. However, there has been increased media coverage, an action often connected to legislative responses, particularly at the state level. A number of legal and state policy and regulatory actions have occurred since the U.S. Department of Education report on Educator Sexual Misconduct was released (Shakeshaft, 2004). In an area where prevention is most often pushed to the victim in the form of “Good Touch, Bad Touch” and other initiatives that rely upon children to protect themselves, it is of worth to analyze the merits of state and federal policy and case law as a deterrent to educator sexual misconduct. The purpose of this paper is to examine educator sexual misconduct in light of U.S. legal and regulatory decisions between 2004 and 2013, years that have seen considerable change at the state level, increased payouts in civil cases, and a slightly expanded federal judicial interpretation of liability. These regulations will then be compared to international policy and law in an effort to understand the international problem of educator sexual misconduct. This paper examines 7 categories of legal actions that have occurred since the release of the U.S. Department of Education study (2004) through a content analysis of these state legislative actions and of state and federal case law, for the purpose of testing the likelihood of a reduction of child sexual abuse in schools. The paper details the rationale behind state actions as well as the tensions between levels of government and the court system. Further, a number of unintended consequences of state legislative action are discussed. These U.S. actions are then placed in the context of international law. State legislation has focused on several key areas: Required screening of educational personnel, assigning liability to districts that fail to reveal misconduct of former employees being vetted by other districts, penalties for failure to report alleged educator sexual misconduct to criminal authorities, penalties for failure to report possible educator sexual misconduct to state licensing boards, reduction in statutes of limitations, and changes in sovereign immunity laws in cases of educator sexual misconduct. While there are several sources that present and discuss the foundations of the laws that govern educator sexual misconduct, there are no studies that examine the impact of initiatives or trace the legal reasoning of current federal law. This paper will place the following within an international context for preventing the sexual abuse of children by school professionals. 1. Federal laws. The primary federal legal remedy for sexual misconduct in schools is Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972. 2. State child sexual abuse laws. Depending upon a number of factors (age of student, age of educator, type of sexual misconduct, etc.) educators who sexually abuse might be prosecuted under a variety of statutes. Criminal codes are not uniform across the states. 3. State sexual assault laws. While sexual assault laws prohibiting coercive or forced sex cover some types of educator sexual misconduct, these laws don’t cover all of the ways in which educators might sexually abuse students. 4. State educator sexual misconduct laws. In addition to general sexual assault laws and criminal statutes prohibiting adult sexual contact with children, some states have adopted laws that specifically prohibit sexual abuse by educators or people in a position of trust. 5. Limitations of state laws. From a national perspective, there are several drawbacks to using state statutes to address educator sexual misconduct. (1) Many of the laws include only students who have not reached the age of consent and the age of consent differs by state; (2) Many do not require those found guilty under these statutes to register as sex offenders (see, for instance, Nevada Revised Statutes: Chapter 201); (3) There is no uniform legal definition of child sexual assault or criminal sexual activity from state to state; (4) There is no uniform penalty for similar actions across the states; and (5) The age of minors varies by state. 6. Tenure and licensure. Besides federal, civil and criminal approaches to identifying and stopping educator predators, legally enforceable codes of professional conduct, generally in connection with state licensure, exist in most states. 7. Laws on fingerprinting and background checks Many states have passed fingerprinting laws for teachers and other educational professionals. However, there are no data about the effectiveness of such legislation for preventing or detecting sexual abusers. Children cannot learn in a school climate that is sexualized and in which they are at risk for sexual abuse. The ACE studies clearly document that children who are sexually abused are at risk for poor performance in schools, among other outcomes. This paper is related to subtheme 1, as it explores both sexual abuse within schools and the legal approaches that have international currency.