TRANSLATION AND READING

advertisement

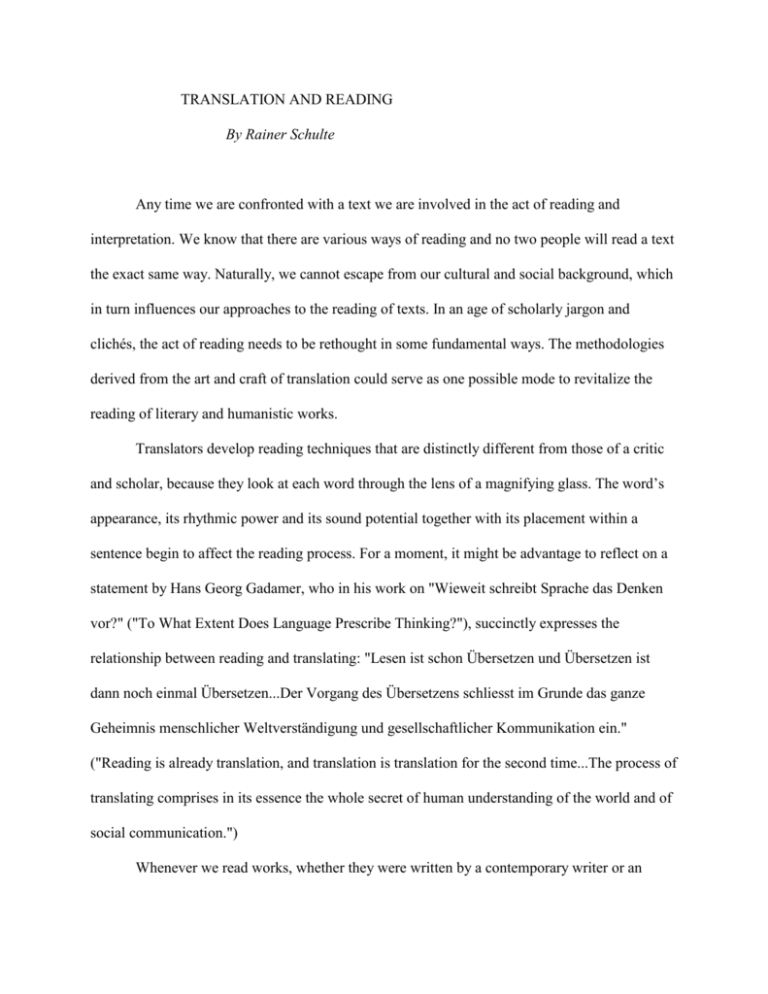

TRANSLATION AND READING By Rainer Schulte Any time we are confronted with a text we are involved in the act of reading and interpretation. We know that there are various ways of reading and no two people will read a text the exact same way. Naturally, we cannot escape from our cultural and social background, which in turn influences our approaches to the reading of texts. In an age of scholarly jargon and clichés, the act of reading needs to be rethought in some fundamental ways. The methodologies derived from the art and craft of translation could serve as one possible mode to revitalize the reading of literary and humanistic works. Translators develop reading techniques that are distinctly different from those of a critic and scholar, because they look at each word through the lens of a magnifying glass. The word’s appearance, its rhythmic power and its sound potential together with its placement within a sentence begin to affect the reading process. For a moment, it might be advantage to reflect on a statement by Hans Georg Gadamer, who in his work on "Wieweit schreibt Sprache das Denken vor?" ("To What Extent Does Language Prescribe Thinking?"), succinctly expresses the relationship between reading and translating: "Lesen ist schon Übersetzen und Übersetzen ist dann noch einmal Übersetzen...Der Vorgang des Übersetzens schliesst im Grunde das ganze Geheimnis menschlicher Weltverständigung und gesellschaftlicher Kommunikation ein." ("Reading is already translation, and translation is translation for the second time...The process of translating comprises in its essence the whole secret of human understanding of the world and of social communication.") Whenever we read works, whether they were written by a contemporary writer or an 2 author from the past, we have to translate them into our present sensibility. Reading is a continuous process of translation, and the way the translator looks at every word and investigates its rhythmic power and its semantic possibilities reaffirms that the act of reading, seen through the translator’s eyes, is dynamic and not static. The writer creates the text and the reader as translator is involved in a constant process of re-creating the text. In the process of recreating the situations in a work, each translator brings a modified interpretation to the text, which clearly negates the assumption that literary works can be reduced to one final, definitive meaning. Correspondingly, there cannot be one definitive translation of a poem, a novel, or a play. The many translations that have been published of the poem “The Panther” by Rainer Maria Rilke shows how many different interpretations there can be of one single poem. The very nature of translation thinking leads to the acceptance of multiple meanings and interpretations. Through the process of reading, we the readers are transplanted into the atmosphere of a new situation the reality of which has to be deciphered by the reader, which can lead to a variety of interpretive approaches. Even though words appear as fixed entities on the page, the translator focuses on the uncertainty inherent in words whose contours can never be fully delineated. Words exist as isolated phenomena and as semiotic possibilities within a sentence, paragraph, or the context of an oeuvre. The rediscovery of that uncertainty in each word constitutes the initial attitude of the translator. Reading becomes a continuous process of making meaning and not the description of already existing fixed meanings. As the imaginative text does not offer the reader a new comfortable reality but, rather, places him between several realities among which he has to choose, the words that constitute the text emanate a feeling of uncertainty. That feeling, however, becomes 3 instrumental in the reader/translator's engagement in a continuous process of decision-making. Certain choices have to be made among all these possibilities of uncertain meanings. Whatever the translation decision might be, there is still another level of uncertainty for the reader/translator, which continues the process of reading not only within the text but even beyond the text. This proliferation of uncertainties must be viewed as one of the most stimulating and rewarding results that the reader/translator perspective finds in the study and experience of the text: Reading as the generator of uncertainties, reading as the driving force toward a decisionmaking process, reading as discovery of new interrelations that can be experienced but not described in terms of a critical, content-oriented language. In general, readers are inclined to ask the question: what does a text mean? The response to such a question would reduce the multiplicity of possible interpretations inherent in a text to one single answer. However, the translator thinks in different terms. The initial question might be changed from “what does a text mean” to “how does a text come to mean?” That change of perspective reorients the techniques of reading, since it is extremely difficult to define the exact parameters of a word’s meaning. As soon as a word is placed next to another word, some of the original meaning-contours of each word begin to be modified. Perhaps the major contribution that translation thinking brings to the act of reading is the translator’s practice of seeing words not as isolated phenomena but rather as linkages to other words. To comprehend the overall atmosphere and an author’s direction of thinking in a given work, the translator deciphers the direction of thinking that a particular word projects. That form of horizontal thinking through a poem can easily be illustrated in Pablo Neruda’s poem “Arte Poetica” that opens in the following way, “Entre espacio y sombra.” (between space and shadow). Both words indicate a movement 4 of expansion. Keeping that characteristic in mind the reader can then proceed through the poem to look for other nouns, verbs, or adjectives that suggest a similar movement of expansion. And indeed the poem abounds with words that suggest a movement of expansion: dream, wind, sound, bell, smell, noise, and a ceaseless movement. Reading from a translator's point of view represents a continuous process of opening up new possibilities of interactions and semantic associations. In the translation process there are no definitive answers, only attempts at solutions in response to states of uncertainly generated by the interaction of the words' semantic fields, sounds, and visual appearance on the page. The reconstruction of these associations differ with each reader and translator, which is ultimately responsible for the varied interpretations that are generated by different readers of the same text. The proliferation of multiple translations that many novels, and especially poems have undergone, confirm the existence of different interpretations generated by the same text. Reading institutes the making of meanings through questions in which the possibility of an answer results in another question: What if? The translator/reader makes the reading activity a process in which each word begins to assume possible semantic associations which prevents the act of interpretation to become static. Applying the translator's eye to the reading of a text changes our attitude toward the reading process by dissolving the fixity of print on a page into a potential multiplicity of semantic connections that support the overall atmosphere encountered in a novel or poem. The words on the page represent only a weak reflection of the situations that the author intended to express. The translator/reader considers the word a means to an end, the final destination of which can never be put into the limitations of static formulations. 5 The methodologies of translation can therefore be used to reactivate the act of reading as a dynamic process that engages the reader in the experience of the literary work.