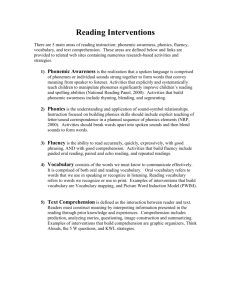

To examine the relationship between word decoding and

advertisement