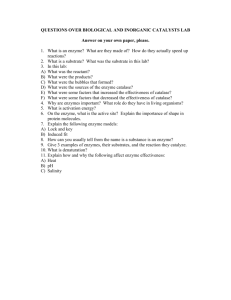

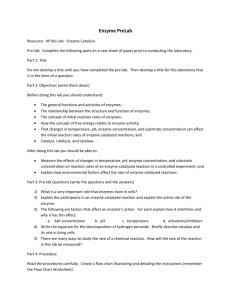

Physiology Lecture Outline: Enzymes

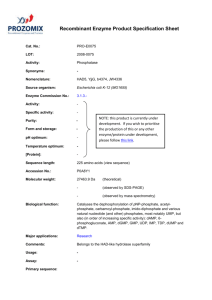

advertisement

Physiology Lecture Outline: Enzymes

Chemical Reactions in the body

Catalysts function to speed up the rate of a chemical reaction by lowering the activation energy required

and is not altered or consumed in the process.

Enzymes are proteins that function as biological catalysts and the human body contains 1000's of

different types of enzymes.

A Substrate is a molecule that can bind to an enzyme in a specific way and undergo a chemical reaction

as a result. They are like reactants in a spontaneous chemical reaction (but are called substrates when

enzymes are involved) and they are transformed into products.

All enzymes are proteins with specific 3-D shapes and they contain small regions where substrates bind to

the enzyme called the active site. Enzymes carry out catalysis by binding to substrate molecules and

bringing them close together and at the same time stressing certain substrate chemical bonds so that the

energy required to reach a certain transition state is lowered. The result is that the reaction occurs much

more rapidly (typically millions of times faster) than it would without enzymes.

The active site of an enzyme is often a small region within the larger binding site. In some cases, the

active site is not part of the binding site but is adjacent to it or is in a position that allows it to interact with

the substrates once they're bound to the binding site.

Enzyme Specificity

Specificity is ability of enzyme to catalyze only certain reaction(s). Some enzymes are very specific, such

as glucokinase, it catalyzes this reaction: glucose + Pi

glucose 6-P. Other enzymes have broader

specificities, such as peptidases, which work on all peptide bonds.

Enzyme-Substrate Complex - is the combination of an enzyme and it substrates bound to it at the active

site. When they dissociate, the products are formed and the enzyme is free to bind new substrates. There

are two ways that enzyme-substrate specificity can be described: 1) Lock and Key or 2) Induced Fit.

1) Lock and Key - describes when the active site of the enzyme is highly specific to the shape of the

substrate, with a complimentary fit, like a lock and key arrangement. This is a convenient way to think

about enzyme-substrate binding, as we are familiar with locks and keys. For example, we understand that

very small changes in the ‘cut’ of a key will mean it will only work with a lock that is an exact match for

it. Enzyme and substrate binding behavior is much more complex, but this is a good place to start.

2) Induced Fit - describes when the initial shape of the active site is not necessarily highly specific to the

substrate. As the substrate approaches the enzyme, it induces a change in the shape of the active site, for a

better fit. These are also called conformational changes. This model can accommodate for a wider range

of substrates and explains reversible reactions better than the lock and key model.

2

Biochemical or Metabolic Pathways

Enzymes are crucial in creating and maintaining metabolic pathways - these are discrete and ordered

sequences of enzymatically mediated chemical reactions, in which the products of one reaction become

the substrates for the next in the sequence, and so on, until the end.

e1

e3

e2

A

Substrate

B

C

Intermediates

D

End Product

Figure 1. An example of a general metabolic pathway in which a substrate is converted into intermediates

and then products by a series of different enzymes. A typical way to control this pathway is by turning the

enzyme off (X) or on () at the beginning of the pathway, thus changing the amount of end product.

Allosteric Inhibition (or End Product Inhibition) - this is a way of controlling the rate of production of a

metabolic pathway. If the concentration of the end product in a pathway increases, it binds to the enzyme

catalyzing the first step in the pathway (e1). It binds at a site other than the active site, and in doing so it

reduces the ability of the enzyme to bind substrates at the active site and thus slows or stops the metabolic

pathway at the beginning. Therefore, the production of the end product is reduced or no longer made. If

this substance begins to get used up again, the concentration will decrease enough so as not to inhibit e 1

any longer; the pathway resumes and more end product is made.

A specific example of this process is seen in the production of the important neurotransmitter

norepinephrine (NE), which is derived from the amino acid tyrosine. In a series of enzymatically

catalyzed reactions, NE is the end product (as in Fig 1. above). The body is conservative and typically

does not want to make something when it is not needed. Thus, if NE is not being used at the rate it is

being synthesized, the pathway needs to be inhibited or shut off. What type of homeostatic mechanism is

this? A ___________ Feedback Loop!

Naming of Enzymes

By convention, most enzymes end with ase and typically their name indicates their function or the

substrates they bind.

For example, phosphotase - removes phosphates from molecules; kinase - adds phosphates to molecules;

dehydrogenase - removes Hydrogens; hydrolase - adds H2O; polymerase - assembles polymers;

isomerase - rearranges atoms in a molecule; synthase - dehydration synthesis reactions; carbonic

anhydrase - removes H2O from carbonic acid; amylase - digests starch; lipase - digests lipids; protease digests proteins.

Enzyme Activation

Not all enzymes are synthesized in a form that is ready to catalyze a reaction. There are 3 main ways in

which an enzyme can be 'activated' if it is initially synthesized in its inactive form.

3

1. Some enzymes require proteolytic ('breaking of protein') activation. If an enzyme is made in its

inactive form it will remain that way until it is cleaved (cut) by other enzymes (or conditions) to become

activated. This typically involves shortening the polypeptide chain.

e.g.

Pepsinogen

+

(long peptide)

(inactive)

HCl

Pepsin

(shorter peptide)

(active)

Often the enzymes requiring proteolytic activation do not have the conventional -ase ending to their

names. The inactive forms of the protein often have suffix -ogen attached, e.g., pepsinogen (inactive) pepsin (active). As we will see later, angiotensinogen is an important precursor to angiotensin I and II.

Other enzymes require cofactors or coenzymes associated with the enzyme in order for the enzyme to

function properly.

2. Cofactors - are inorganic, non protein components required for substrate binding at the active site.

Typically it is a metal ion that binds to the enzyme and activates its catalytic function. These include:

Fe3+, Fe2+, Cu2+, Ca2+, Mg2+ and Mn2+. All induce conformational changes.

3. Coenzymes - usually small organic molecules typically derived from a vitamin, which is needed to

make an enzyme catalytically active. They act by accepting electron from an enzymatic reaction and

transferring them to a different reaction chain. For example, NAD+ (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide)

shuttles electrons from glycolysis to the electron transport chain for aerobic respiration.

Specific examples of how a variety of foods provide you with the required co-enzymes:

FAD (riboflavin); found in eggs, lean meats, milk and broccoli.

NAD, NADP niacin (nicotinic acid); found in meats, cereals and leafy greens.

Coenzyme A (pantothenic acid precursor); found in meat, cereal, milk, eggs and vegetables.

Factors that Effect Enzyme Activity

Once an enzyme is active, there are several things that can modulate (change) the level of activity of an

enzyme. These modulators can include pH, temperature, other molecules and covalent bonds. They can

inhibit or activate enzyme activity.

1. Acidity/Alkali

Enzymes function within certain pH ranges. Changes in pH alter tertiary structure of enzyme. Even small

changes in pH can increase or decrease enzyme activity. Beyond a critical level (outside of its optimal pH

range) the enzyme is denatured.

e.g., compare enzymes of the mouth, stomach and small intestine.

2. Temperature

Enzymes also function within certain and temperature ranges, typically most enzymes in the human body

have an optimal level of activity at around normal body temperature (96.7oF or 37.6oC). Again, changes

alter tertiary structure of enzyme and small changes in temperature can increase or decrease enzyme

activity. Beyond a critical level, the enzyme is denatured.

e.g., think of the effect of a fever on enzymes of the body.

4

3. Chemical Modulators

Chemical modulators are molecules that bind to enzymes and alter their catalytic ability. They can bind

directly to the active site (Competitive inhibitors) or at an area other than the active (Non-Competitive

inhibitors).

A) Competitive Inhibitors may be molecules that bind to the active site without being acted on by the

enzyme. Many are similar enough in structure to bind to the active site and then block the true substrate

from occupying the site, thus inhibiting the chemical reaction. In other cases, the competing molecule is a

substrate that can be acted on by the enzyme and this reaction will take place and again the reaction for

the true substrate will be inhibited.

There are some interesting examples of competitive inhibitors. Ethylene glycol, better known as

antifreeze, is a poison that kills about fifty people each year. In the body, ethylene glycol is converted to a

toxic compound called oxalic acid by the enzyme alcohol dehydrogenase.

The treatment for ethylene glycol poisoning is administration of ethanol. Ethanol is also a substrate for

alcohol dehydrogenase, so it competes with ethylene glycol for the alcohol dehydrogenase binding site.

When ethanol is administered after ingestion of ethylene glycol, it binds to alcohol dehydrogenase

preferentially in place of ethylene glycol. This blocks the production of oxalic acid and decreases the

toxic effects of ethylene glycol ingestion.

B) Non-Competitive Inhibitors bind to the enzyme at some site other than the active site. They do not

affect enzyme-substrate binding but in some other manner inhibit the enzyme from catalyzing the

reaction. Some noncompetitive inhibitors act by binding to the inorganic ion cofactors of enzymes.

4. Allosteric Modulators - these bind away from active site but alter its configuration and can increase or

decrease the enzyme’s affinity for substrates.

Covalent Modulators - these modulators bind covalently to enzyme. They do not make covalent bonds at

the active site but when the covalent bond is formed, the shape of the enzyme changes. This change in

shape alters the three dimensional shape of the binding site, thus altering the affinity that the enzyme will

have for the substrate(s). Two very important covalent modulators are 1) changes in the concentration of

intracellular calcium ions ([Ca2+]i); and 2) adding or removing phosphate groups. and affect enzyme's

ability to decrease activation energy, e.g., calcium ions (Ca2+) are an important covalent modulator.

Changes in free intracellular calcium concentrations often act as signals by binding to enzymes such as

protein kinase C or control proteins such as calmodulin in smooth muscle.

Enzyme and Substrate Concentration Affect the Reaction Rate

The rate of enzymatically catalyzed reactions is assessed by measuring product synthesis or substrate

consumption.

1. Reaction Rate is Directly Related to the Amount of Enzyme Present.

If the substrate concentration ([substrate]) is kept constant, then the more enzyme that is present, the

greater the rate of the reaction (i.e., the more product is produced).

2. Reaction Rate is Related to the Amount of Substrate Present and can Reach a Maximum.

If the enzyme concentration ([enzyme]) is held constant, the reaction rate will increase as [substrate]

increases but there is a limit to how fast a reaction can go, if [enzyme] is the limiting factor. The enzyme

becomes saturated with substrate and reaches a maximum saturation point. At enzyme saturation, the

enzyme is catalyzing reactions as fast as it can.

5

Reversible reactions, Reaction Rate, and the Law of Mass Action

Reversible reactions go to a state of equilibrium, where the forward reaction rate = reverse reaction rate.

For example, adding more substrate increases the forward reaction rate and more product forms. The Law

of Mass Action is part of LeChatelier's principle, which states that if a system at equilibrium is disturbed

by a change in concentration of one of the components or in temperature or pressure, the system will shift

until a new equilibrium is reached. Law of Mass Action can also be described this way:

The direction the equation will be driven (forward or reverse) is dictated by the amount of reactant

(substrates) or products present; the direction of the reaction will be to decrease whatever is in

abundance, until equilibrium is reached. At reaction equilibrium, the ratio of substrates to products

is always the same; the system adjusts the ratio until equilibrium is restored.

The following enzymatic reaction is an important reversible reaction which takes place in the body:

CO2 + H2O

substrates

carbonic

anhydrase

H2CO3

H+ + HCO3products

Assume that the reaction is at equilibrium. The concentration of H+ is decreased by some outside force.

Once the equilibrium state has been restored according to the Law of Mass Action, what will have

happened to the concentrations of the following? (You do not need to know the relative concentrations of

the substrates and the products or the equilibrium constant K in order to answer this question).

CO2? (decreases); HCO3-? (increases); H2O? (decreases; but in the body, is present in such excess that this

is not significant)

The interaction of enzymes with modulators can both cause diseases and be used to treat them. Many of

the substances we call poisons such as cyanide, mercury, arsenic, and methyl alcohol exert their toxic

effect by inhibiting essential enzymes. On the other hand, drugs used for the treatment of Parkinson's

disease and some types of depression, work by inhibiting the enzyme monoamine oxidase (MAO). This

enzyme catalyzes the breakdown of the neurotransmitters norepinephrine and serotonin. Eldepryl

(selegiline) combines irreversibly with the active site of MAO, preventing serotonin and norepinephrine,

the normal substrates, from binding to MAO; as a result, their levels in the body don't decrease as rapidly

and their activity is enhanced.

Enzymes and Reversible Reactions

The body regulates reversibility to control metabolism. If a single enzyme controls both the forward and

reverse reactions then the product concentration will be governed by Law of Mass Action only and the

reaction can't be closely regulated. If there are separate enzymes, one for the forward, the other for the

reverse reaction, then these pathways can be regulated more closely.

The synthesis of glucose from glucose 6-phosphate is an important example of a one-way path. All tissues

have the pathway needed to add the phosphate to glucose, but only the liver and kidneys have the enzyme

needed to remove the phosphate from glucose (glucophosphotase). The presence of irreversible steps in a

metabolic pathway provides the cell with an important means of controlling its metabolism. It also

requires that cells cooperate with each other. Since skeletal muscle cells can't make glucose, they must

either find alternate sources of energy or send their chemical intermediates to the liver so that the liver can

turn them into glucose. The glucose produced by the liver then returns to the muscles via the blood. This

is a perfect example of how cooperation between the body’s individual cells (trillions of them) is the

fundamental concept which enables the success of the whole organism.