Reading ASSIGNMENT: Swift, “A Modest Proposal” -

advertisement

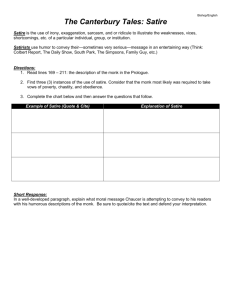

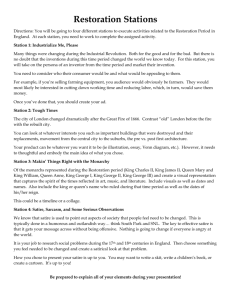

READING ASSIGNMENT: Swift, “A Modest Proposal” -- Read this and annotate “Modest Proposal” using the reading questions below as your guide. (I won’t pick up the reading questions; I will assess your annotation.) John Dryden’s A Discourse Concerning the Original and Progress of Satire 1693 Excerpt from poet and playwright John Dryden's Discourse concerning the Original* and Progress of Satire [1693]: he presents a partial, historical definition of satire. "If we take satire in the general signification of the word, as it is used in all modern languages, for an invective*, it is certain that it is almost as old as verse....After God had cursed Adam and Eve in Paradise, the husband and wife excused themselves by laying the blame on one another, and gave a beginning to those conjugal dialogues in prose which the poets have perfected in verse." Dryden goes on to say that, contrary to common opinion, the word SATIRE does not derive from satyr, "that mixed kind of animal, or as the ancients thought him, rural god, made up betwixt a man and a goat, with a human head, hooked nose, pouting lips...pricked ears, and up-right horns, the body shagged with hair, especially from the waist, and ending in a goat, with the legs and feet of that creature." That is, satire does not derive from this a sexually lascivious creature and its behavior. Rather, Dryden says, "it is grounded on sure authority, that satire was derived from satura, a Roman word which signifies full and abundant, and full also of variety, in which nothing is wanting to its due perfection. Satura, as I have formerly noted, is an adjective, and relates to the word lanx...in English a charger or large platter, [which] was yearly filled with all sorts of fruits, which were offered to the gods of their festival." Of MENIPPEAN SATIRE, Dryden says this: "This sort of satire was not only composed of several sorts of verse but was also mixed with prose....sprinkled with a kind of mirth and gaiety, yet many things are there inserted which are drawn from the very entrails of philosophy; and many things severely argued...mingled with pleasantness on purpose, that they may more easily go down with the common sort of unlearned readers." [Dryden here is quoting an early Menippean satirist, Varro.] Dryden goes on to say that in this type of satire, the "subjects were various." Dryden on HORATIAN and JUVENALIAN SATIRE: First, Dryden quotes a famous critic who disparaged Horace for the humor of his satire. “‘A perpetual grin, like that of Horace, rather angers than amends a man.’ I cannot [Dryden retorts] give him up the manner of Horace in low satire so easily. Let the chastisement of Juvenal be never so necessary for his new kind of satire; let him declaim* as wittily and sharply as he pleases; yet still the nicest [i.e. most refined] and most delicate touches of satire consist in fine raillery [good-humoured banter]. This, [Horace], is your particular talent, to which even Juvenal could not arrive....How easy is it to call rogue and villain, and that wittily! But how hard to make a man appear a fool, a blockhead, or a knave, without using any of those opprobrious terms! To spare the grossness of the names, and to do the thing yet more severely, is to draw a full face, and to make the nose and cheeks stand out, and yet not to employ any depth of shadowing. This is the mystery of that noble trade [Horatian satire]....Neither is it true that this fineness of raillery* is offensive. A witty man is tickled while he is hurt in this manner, and the fool feels it not. The occasion of an offense may possibly be given, but he cannot take it. If it be granted that in effect this way does more mischief, that a man is secretly wounded, and though he be not sensible himself, yet the malicious world will find it out for him; yet there is still a vast difference betwixt the slovenly butchering of a man, and the fineness of a stroke that separates the head from the body, and leaves it standing in its place. A man may be capable...of a plain piece of work, a bare hanging, but to make a malefactor* die sweetly [is an art].” Definitions (lifted from the American Heritage Dictionary): o·rig·i·nal (…-r¹j“…-n…l) 4. Archaic. The source from which something arises; an originator. [Middle English, from Old French, from Latin orºgin³lis, from orºg½, orºgin-, source. See ORIGIN.] in·vec·tive (¹n-vµk“t¹v) n. 1. Denunciatory or abusive language; vituperation. 2. Denunciatory or abusive expression or discourse. --in·vec·tive adj. Of, relating to, or characterized by denunciatory or abusive language. [From Middle English invectif, denunciatory, from Old French, from Late Latin invectºvus, reproachful, abusive, from Latin invectus, past participle of invehº, to inveigh against. See INVEIGH.] --in·vec“tive·ly adv.--in·vec“tive·ness n. de·claim (d¹-kl³m“) v. de·claimed, de·claim·ing, de·claims. --intr. 1. To deliver a formal recitation, especially as an exercise in rhetoric or elocution. 2. To speak loudly and vehemently; inveigh. --tr. To utter or recite with rhetorical effect. [Middle English declamen, from Latin d¶cl³m³re : d¶-, intensive pref.; see DE- + cl³m³re, to cry out; see kel…-2 below.] --de·claim“er . rail·ler·y (r³“l…-r¶) n., pl. rail·ler·ies. 1. Good-natured teasing or ridicule; banter. 2. An instance of bantering or teasing. [French raillerie, from Old French railler, to tease. See RAIL3.] mal·e·fac·tor (m²l“…-f²k”t…r) n. 1. One that has committed a crime; a criminal. 2. An evildoer. [Middle English malefactour, from Latin malefactor, from malefacere, to do wrong : male, ill; see mel-3 below + facere, to do; see dh¶- below.] --mal”e·fac“tion (-f²k“sh…n) n. . . . [an] important Secret, in the designing of a perfect Satire; that it ought only to treat of one Subject; to be confin'd to one particular Theme; or, at least, to one principally. If other Vices occur in the management of the Chief, they shou'd only be transiently lash'd, and not be insisted on, so as to make the Design double 1. 2. Under this Unity of Theme, or Subject, is comprehended another Rule for perfecting the Design of true Satire. The Poet is bound, and that ex Officio, to give his Reader some one Precept of Moral Virtue; and to caution him against some one particular Vice or Folly: Other Virtues, subordinate to the first, may be recommended, under that Chief Head; and other Vices or Follies may be scourg'd, besides that which he principally intends. But he is chiefly to inculcate one Virtue, and insist on that. Thus Juvenal in every Satire, excepting the first, tyes himself to one principal Instructive Point, or to the shunning of Moral Evil. Even in the Sixth, which seems only an Arraignment of the whole Sex of Womankind; there is a latent Admonition to avoid Ill Women, by shewing how very few, who are Virtuous and Good, are to be found amongst them. But this, tho' the Wittiest of all his Satires, has yet the least of Truth or Instruction in it. He has run himself into his old declamatory way, and almost forgotten, that he was now setting up for a Moral Poet. The Scribelrus Club The Age of Enlightenment, an intellectual movement in the 17th and 18th century advocating rationality, produced a great revival of satire in Britain. This was fuelled by the rise of partisan politics, with the formalisation of the Tory and Whig parties - and also, in 1714, by the formation of the Scriblerus Club, which included Alexander Pope, Jonathan Swift, John Gay, John Arbuthnot, Robert Harley, Thomas Parnell, and Henry St John, 1st Viscount Bolingbroke. This club included several of the notable satirists of early 18th century Britain. They focused their attention on Martinus Scriblerus, "an invented learned fool...whose work they attributed all that was tedious, narrow-minded, and pedantic in contemporary scholarship". The club began as a project of sairizing the abuses of learning wherever they might be found. In their hands astute and biting satire of institutions and individuals became a popular weapon. Reading Questions: initially, * What does the speaker find "melancholy" in Ireland? *Note the interesting distinction in the first line. Does the speaker finds it depressing that such impoverished people exist? Or does he find it depressing to see such people? Do you think the speaker's sympathies are with the suffering lower class? Or with the poor rich class that has to look at them everyday? 1. “A Modest Proposal” is an ironic essay: the author deliberately writes what he does not mean. What is the real thesis? Is there more than one? 2. A clear difference exists between Swift and the persona who makes this proposal. Characterize the proposer. 3. Would it be possible to read this essay as a serious proposal? 4. Look closely at paragraphs 4, 6, and 7, and study how the appeals to logic are put in mathematical and economic terms. Underline those words and phrases. 5. When does the reader begin to realize that the essay is ironic? Before or after the actual proposal is made in paragraph 10? 6. Which groups of people are singled out as special targets for Swifts’ attack? Are the Irish presented completely as victims, or are they also to blame? 7. Does the essay merely function as a satirical attack? Does Swift ever present any serious proposals for improving conditions? If so, where? 8. What is the purpose of the last paragraph?