POLYNESIAN OCEAN MIGRATIONS AND EXPLORATIONS

advertisement

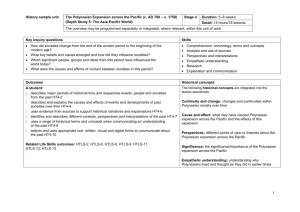

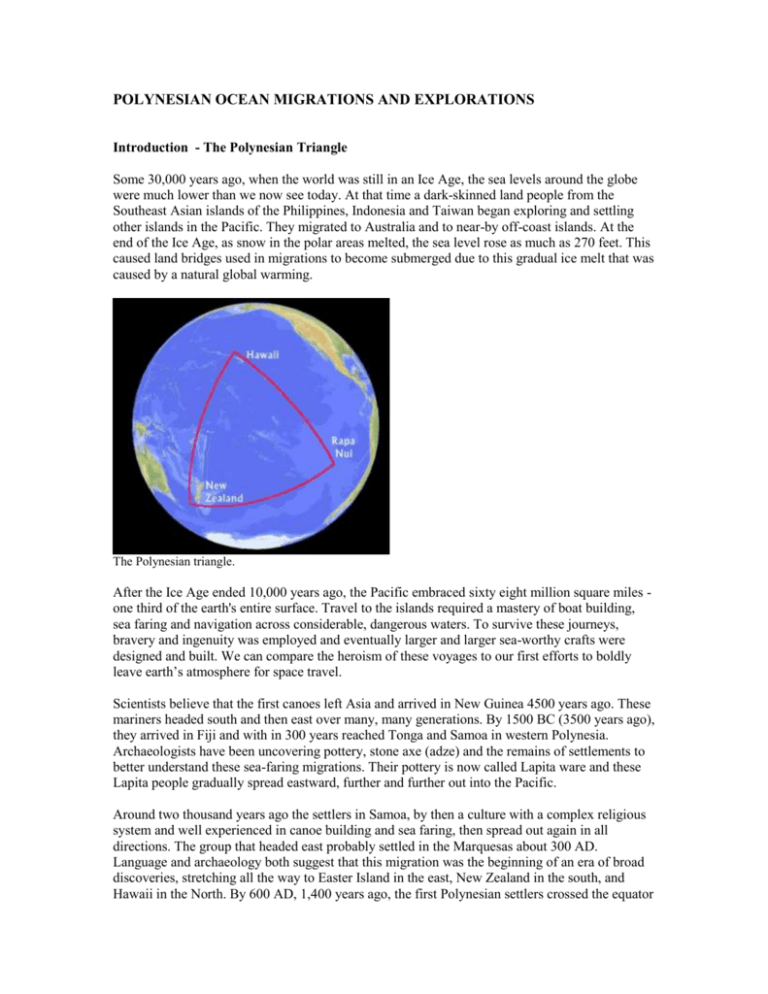

POLYNESIAN OCEAN MIGRATIONS AND EXPLORATIONS Introduction - The Polynesian Triangle Some 30,000 years ago, when the world was still in an Ice Age, the sea levels around the globe were much lower than we now see today. At that time a dark-skinned land people from the Southeast Asian islands of the Philippines, Indonesia and Taiwan began exploring and settling other islands in the Pacific. They migrated to Australia and to near-by off-coast islands. At the end of the Ice Age, as snow in the polar areas melted, the sea level rose as much as 270 feet. This caused land bridges used in migrations to become submerged due to this gradual ice melt that was caused by a natural global warming. The Polynesian triangle. After the Ice Age ended 10,000 years ago, the Pacific embraced sixty eight million square miles one third of the earth's entire surface. Travel to the islands required a mastery of boat building, sea faring and navigation across considerable, dangerous waters. To survive these journeys, bravery and ingenuity was employed and eventually larger and larger sea-worthy crafts were designed and built. We can compare the heroism of these voyages to our first efforts to boldly leave earth’s atmosphere for space travel. Scientists believe that the first canoes left Asia and arrived in New Guinea 4500 years ago. These mariners headed south and then east over many, many generations. By 1500 BC (3500 years ago), they arrived in Fiji and with in 300 years reached Tonga and Samoa in western Polynesia. Archaeologists have been uncovering pottery, stone axe (adze) and the remains of settlements to better understand these sea-faring migrations. Their pottery is now called Lapita ware and these Lapita people gradually spread eastward, further and further out into the Pacific. Around two thousand years ago the settlers in Samoa, by then a culture with a complex religious system and well experienced in canoe building and sea faring, then spread out again in all directions. The group that headed east probably settled in the Marquesas about 300 AD. Language and archaeology both suggest that this migration was the beginning of an era of broad discoveries, stretching all the way to Easter Island in the east, New Zealand in the south, and Hawaii in the North. By 600 AD, 1,400 years ago, the first Polynesian settlers crossed the equator and sailed north to arrive in Hawaii, probably landing near South Point on the Big Island. A second wave of migration arrived four hundred years later around 1000 AD. After that, the European arrival in the 1700s (possibly an occasional contact in the 1500s) was the next contact the isolated Hawaiians had with other peoples. Centuries before the Europeans dared to sail out across the oceans, far away from the sight of land, these daring Polynesians had the skill, knowledge, and motivation to explore and settle a triangle of open ocean that stretched from a latitude as far north as Baja California and as far south as the tip of South America. Hawaii was the settlement at the northern point of this Polynesian triangle; Easter Island was the south eastern point of the triangle; New Zealand the southwestern point, and in between lie many island chains and atolls populated or visited by these early sea faring Polynesians. While these points of the Polynesian triangle mark by where settlements have been found from this early sea-going period, it is quite possible they do not mark the boundaries of their explorations. Scientists are exploring the possibility that these bold sailors also ventured on journeys further out, beyond the boundaries of the settled triangle, and may have visited South America and the coast of North America. Let's first learn more about the canoes the ancient Polynesians may have used to reach Hawaii and other possible locations. Then we will explore potential evidence of possible broader intercultural, trans-Pacific exchanges. Scientists have only recently begun exploring the possibility of Polynesian contact with Native Californians examining canoe building and linguistic similarities. The idea of South American and Polynesian contact has been under consideration for a longer time periods, with the appearance of the South American sweet potato in Polynesia one of the most concrete examples of contact, and the sailing trip of Thor Heyerdahl on the Kon-Tiki in 1947 as another suggestion that such navigation was indeed possible. The most controversial theory of early contact, one that has yet to be accepted by scientists but is still a topic of exploration, is the possible existence of tablets from the purported lost content of Mu found in Mayan temples in Mexico. The Polynesian Voyaging Canoes - technology and navigation Ancient Polynesian Voyaging The most common voyaging canoe made by the early Polynesian explorers was a double hulled craft with each hull formed in a wide V for stability. Their size was so great that there were no trees large enough to be hollowed out for these massive hulls. Instead, the hulls were very skillfully crafted of wooden planks, cut and fitted using stone adze, sewn together with coconut sennit fibers twisted into rope and then caulked, probably with thick pliable breadfruit sap. Hawaiian Canoe While only a small group could fit in a hollowed log canoe (and then would have to remain sitting as paddlers for the voyage), the large voyaging crafts could hold many families, dogs, pigs, plant tubers and supplies needed to start new farms in uninhabited lands. These large canoes could not only provide room for the sailors and large woven sails, but they would have had room for shelters, bedding and provided a platform for moving about for exercise during long voyages. With plaited hala sails the pair of hulls were lashed close together and had decks spanning the two hulls to connect them for stability and to form the surface to accommodate passengers and supplies. Where a single fisherman or small party could navigate a say fishing trip or short voyage to a neighboring island in a single hulled outrigger made of a hollowed tree, the long, much more uncertain open sea voyaging required the larger double hulled craft for safety and supplies. These large voyaging canoes, in use since at least 2,000 years ago, were the predecessors of the canoes native Hawaiians were using when they first encountered European ships. In comparison, the European ships were slower and harder ot maneuver. A reconstructed double hulled canoe, the Hokulea, averages 100 miles a day on the open sea, sometimes 150 miles a day, outdistancing the European style ships that would have been in use from 1500-1800 during the years that Europeans first began exploring the Pacific. Maritime historians now comment that in addition to being faster and more maneuverable, the Polynesian craft is also better able to hold up in adverse, stormy weather conditions - the most eminently dangerous adversary on the sea. It is also predicted that these double-hulled voyaging craft could safely make journeys of 3,000 to 6,000 miles, giving them a very large potential sphere of influence that might have included reaching and returning from the shores of North and South America. The Easter Island Connection – tip of the triangle and South America Easter Island lies in isolation 2500 miles from South America to its east and 2000 miles from Tahiti to the west. Part of the year the prevailing currents flow from the east, South America, to the west, Polynesia. The other part of the year the currents shift and flow from Polynesia towards South America. Moai of Easter Island. The majority of scientists are certain that Easter Island was settled by Polynesians from the west around 400-600 AD as part of the Great Migrations of Polynesia, but others are exploring the possibility the first Easter Islanders were early sea farers may have been explorers arriving from the east, following the currents from South America. Others suggest that the peoples who came from the east, from South America, were originally from Asia, related directly to the peoples who were settling the western side of the Pacific in Polynesia, but arriving by a different, much longer route. Researchers from the Easter Island Foundation now believe that the orginal inhabitants arrived on this remote island via double canoe and likely arrived by way of Mangareva, probably via Pitcairn, then Easter Island. The Polynesians who settled Mangareva seemingly got there from the Marquesas. Because the Easter Islanders cut down all of their trees, canoe building and sailing died out.There are several images in the Easter Island rock art that scientists believe are pictures of these early voyaging canoes. While scientists hold very different opinions on this issue of who the first people were to inhabit Easter Island and build the famous statues, debate among researchers is an important part of the discovery process. Their debate asks two questions : Was the southeastern point, of what scientists have recently identified as the Polynesian Triangle, settled by Polynesians from the west ? Or was it settled by people of Asian descent from the east, from the South American continent ? Our main concern here in the Voyaging section is to examine whether or not voyages from Polynesia, including from Easter Island, did in fact have a the means to visit South America – beyond the Polynesian Triangle - and, likewise, did the South American’s have the means to visit Polynesia, including Easter Island as the closest land fall. Is it possible – regardless of who arrived first – that both peoples from Polynesian and South America had the ship building and navigation abilities to visit one another and that exchanges of plants and artifacts occurred? Hawai'i to Tahiti and Return: 1976 The first voyage of the Hokule`a from Hawai`i to Tahiti and back took place in 1976, as part of the Bicentenniel Celebration of American Independence. The official purpose of the voyage was to show that the two-way voyages celebrated in Hawaiian oral traditions could be done in a replica of an ancient voyaging canoe navigated without instruments. Hokule'a Arrives in Tahiti, 1976.