Verb nouns: The Core of spoken Cornish – what

advertisement

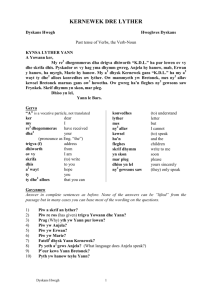

Verb nouns: The Core of spoken Cornish. What makes it truly distinctive from English. Examples of verb-nouns in Cornish are gweles ‘to see’, dybri ‘to eat’, skrifa ‘to write’, etc. A verb-noun in Cornish is often called an infinitive by English grammarians. This can be misleading as a verb-noun in Cornish has many other functions compared to an infinitive in English. A verb-noun can’t be split in Cornish because it consists of a single word. Verb-nouns, in their dictionary form, can combine with any tense or any person of an auxiliary verb, to produce any question, positive statement or negative statement, e.g. A yll’ta gweles? ‘Can you see?’, Hwi a wrug dybri. ‘You (plural) ate/did eat.’, Ny wrons i skrifa. ‘They don’t write.’, etc. The three examples above could be rendered, in high register form, as A welydhta?, Hwi a dheber. and Ny skrifons i. Now, because the high register forms involve conjugating the verb auxiliary verbs combined with verb-nouns are a prominent feature of low register Cornish and hence spoken Cornish. Teaching systems, such as Say Something in Cornish, make use of the fact that verb-nouns can be strung together, e.g. My a vynn dyski kewsel Kernewek. ‘I want to learn to speak Cornish.’ Verb-nouns are also commonly used in conjugation with possessive pronouns, e.g. Dha weles ‘see you (singular)’ literally ‘your to see’. This feature is important if the speaker wants to direct the action of a verb to a subject contained in the second clause of a sentence, e.g. My a vynn y dhybri. ‘I want to eat it.’ literally ‘I want its to eat.’ Verb-nouns are also used in the so called ‘subject dhe infinitive’ construction as used in the second clause of a complex sentence, e.g. My a glewas ev dhe gana. ‘I heard he sings/sang.’, verb-noun kana ‘to sing’. The tense of the secondary clause is taken from the context, primarilythe tense of the primary clause. Verb-nouns are particularly useful as they do not need to be conjugated once the person and the tense has been set by verb that occurs first, My a wrug difuna ha sevel hag omwolghi ha dybri ha mos dhe ober. ‘I did woke up and got up and washed myself and ate and went to work.’ Again this makes for easy fast colloquial Cornish. Some of the above also shows economy, e.g. omwolghi meaning ‘to wash oneself’ and sevel ‘to get up’. Perhaps the versatility of verb-nouns is a factor in their creation; a) from adjectives, e.g. glanhe ‘to clean’ < glan ‘clean’ + -he (verbal suffix) b) from verb-nouns to form a reflexive, e.g. omwolghi ‘to wash’ < om- (reflexive prefix) c) from nouns, e.g. diwrosa ‘to ride a bicycle’ < diwros ‘bicycle’ + -a (verbal suffix) d) from verb-nouns, e.g. dasleverel ‘to repeat’ < leverel ‘to say’ + das- (repeat verbal prefix) e) from English loans, e.g. onderstonya ‘to understand’ with –ya (verbal suffix) f) from verb-nouns, e.g. kammskrifa ‘to miswrite’ < skrifa ‘to write’+ kamm- (verbal suffix) g) from verb-nouns, e.g. diwiska ‘to undress’ < gwiska ‘to dress’ + di- (verbal suffix). Indeed there are many more ways of constructing verb-nouns. It is noteworthy that mutation is featured here – a sort of cement for suffixes, prefixes, nouns and adjectives that builds thousands of verb-nouns! Cornish should follow the other Celtic languages in using the term verb-noun instead of infinitive because verb-nouns are fantastically useful especially in spoken Cornish. Without verb-noun usage there would probably be no spoken Cornish and with spoken Cornish the language of Cornwall could not be considered a living language.